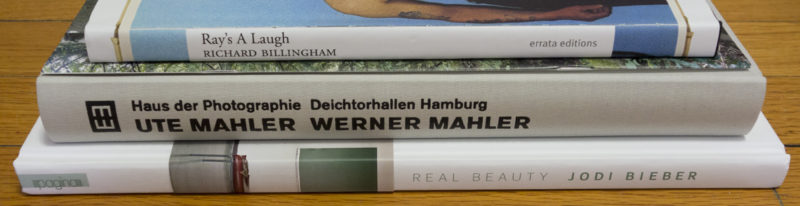

I’m not sure what to make of the selection of books for the most recent Errata Editions books. But then, it’s probably just like which books made it into the Parr/Badger tomes (and which not): to a large extent, it might just be based on personal preferences. That said, I was very excited about the inclusion of Richard Billingham’s Ray’s a Laugh. Most photobooks have much more to offer than the usually handful of images that are widely known, and Ray’s a Laugh is a particularly good example.

If you’re unfamiliar with Errata Editions here is what these “books on books” are. Each volume is dedicated to a single photobook that (usually) is out of print, here Ray’s a Laugh. The photobook in question is fully reproduced in the form of photographs of a collector’s copy (this one is Jeffrey Ladd’s). The Errata Editions books are all the same size, meaning that if the aspect ratios of the photobook in question is very different, things can get a bit iffy. In this particular case, most spreads contain a single spread from the original book. But there are also a few cases of two spreads being shown, one on the left, one on the right page. In addition to the reproduction of the original book, there is a longer essay by a specialist (here Charlotte Cotton), putting the work in perspective, a short essay by Ladd (the mastermind behind the series) with details of the original book, plus a short bio of the photographer.

As someone teaching photography, in particular the history of the photobook and how photobooks work, many of these Errata Editions books are very useful. They make photobooks accessible that otherwise would be unavailable (in this case, the university I’m teaching at has a copy of the original in its library, though). All the various details I outlined above make these books very good research material. But that also is one of the weaknesses of the series: the books never become more than that, given the uniformity of the production and form. So as a collector, I’m still going to be looking for an actual copy of Ray’s a Laugh.

What all of this means is the following: if you buy a copy of Ray’s a Laugh, expecting to get the experience you’re get from looking at the original book, that’s not going to happen. That’s an unrealistic expectation – not a shortcoming of the concept behind the Errata Editions books. If you can look beyond the restriction in form, Ray’s a Laugh has a lot to offer (incl. such goodies as a few reproductions of proof prints or of the original maquette). In particular, if (like me) you don’t have the roughly $300 that a used copy of the original might cost, you’ll get access to a brilliant photobook, however indirectly.

Considerable parts of the history of photography are filled with male photographers taking pictures of mostly younger women, in all states of dress or – usually – undress. This does fit in with the Western history of art in general (see, for example, Kenneth Clark’s The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form), which in itself, however, does not diminish the various aspects of how and why it’s also quite problematic (I attempted to discuss one of them in this piece). Things get even more problematic once you add the portrayal of women in the media, a portrayal that uses and relies on (often heavily retouched) photography to push a very particular image of what a beautiful female body is supposed to look like.

How and why this is extremely problematic is spelled out beautifully in interviews with the women who were photographed by Jodi Bieber for Real Beauty (the book is listed on the German Amazon site, but not on the US one). All of them were photographed in their underwear in (what look like) their own homes, and they each were given the opportunity to talk about their bodies and how they deal with the expectations they run into. And the photographs taken by Bieber belie those very expectations. If the heavily Photoshopped photographs of women on the covers of magazines essentially showcase the beauty of androids, Bieber’s photographs show what real beauty looks like. And the beauty here is included in each and every aspect of the work, including in the very gesture of making it.

We can’t run away from the history of photography. We can’t cherry pick the parts we like and pretend all the nasty ones didn’t (or don’t) exist. It is up to us to learn and know about the many problems photography can create, and we need to confront them. Luckily, as a medium photography can be its own corrective, and Real Beauty makes a very strong case for that. While writing or scientific studies can educate us why contemporary beauty ideals are so problematic, photographs can show us the feeble foundations those ideals rest on.

It is very important that photography itself can be its own corrective: it shows us that it’s not the medium that is flawed. Instead, it’s our uses of it, or – more often – our acceptance of these uses. After all, silence implies consent.

Real Beauty; photographs by Jodi Bieber; essays by Stephan Mann and Steffen Fischer, Jodi Bieber, Ferial Haffajee, Mieke Bal, Pumla Dineo Gqola, Michket Krifa, Lauren Beukes; incl. interviews with the subjects; 107 pages; Pagina; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.6

)

Earlier this year, Hamburg’s Deichtorhallen staged a major retrospective of the work of Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler. A married couple, the two only started working together as photographers a few years ago. Up until then, they photographically went their own ways – with separate projects and commissions. With their East German background, the Mahlers’ work reflects a very specific and still often overlooked part of German photographic history. But it would not do the quality of the photographs any justice to confine it to this particular niche. Much of their photography centers on the human condition (see my recently published piece discussing Ute Mahler’s Zusammenleben), looking at what it is that we do to each other and how we go about our lives.

Neither Ute Mahler nor Werner Mahler has ever shied away from incredibly challenging projects. In 1975, Werner Mahler photographed the inside of a coal mine and its miners hard at work. Because of the intense heat, most workers did their job in the nude (except for boots to protect their feet) – it’s hard to imagine what photographing under such conditions must have been like. In 1993, Ute Mahler photographed a German neonazi, his family and friends.

And then of course, Werner Mahler went to the Berlin Wall the night it was opened, November 9th, 1989. A picture shows groups of men standing on top. It’s a somewhat blurry photograph – light was low for sure, but it’s hard to imagine the photographer’s hands not shaking just a little bit from excitement. Another photograph prominently features a man in a jubilant pose right in front of the Brandenburg Gate. There must have been a flash, the man is lit against the mostly dark background. It’s a moving photograph, a photograph that deserves to find its way into the canon of work done around German reunification.

All of these photographs are included in the catalog from the retrospective, Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler (Kehrer 2014). Unfortunately, its designer went a bit overboard. But that does not take away from the fact that the book deserves to be seen beyond Germany. Never wavering in their firm belief in what makes us all human, Ute and Werner Mahler have been compiling an utterly impressive collection of photographs. They’re still working, their latest body of work – a meditation on the very quiet moments in life – opens us yet another new chapter for them. With so much superficial, flashy and ultimately forgettable photography now being bandied around, these two photographers demonstrate what can be gained from fulfilling the medium’s real promise.

(no ratings for Ray’s a Laugh and Ute and Werner Mahler since the two books aren’t monographs)

Ratings explained here.