Wherever you go these days, the general sentiment appears to be that there are “too many photobooks.” I don’t know whether I buy that. It’s true, there are lots of photobooks being produced, but for me the rule always is: the more, the merrier. But whenever something is popular and getting a lot of attention, the “too many” comments erupt. I remember a few years ago, there was the same kind of talk about photography blogs. After bloggers like yours truly had written about photography for a while, suddenly having a blog and/or reading them became a big craze, and then there were “too many blogs.” Now, a few years later, many blogs have disappeared, and quite a few new ones have entered the scene. Blogs are here to stay, and frankly, those debates about “too many blogs” in retrospect look, well, silly.

I suspect we’ll witness the same development as far as photobooks are concerned. We’re now living through the golden age of the photobook, which is caused by a confluence of various independent factors. For example, digital technologies have made self-publishing much easier and cheaper. The medium photobook itself has found much broader acceptance, its possibilities being explored much more deeply than before. Etc. Just like how a few years ago every photographer thought they needed a blog, now everybody thinks they need to make a photobook. This won’t last. And that’s fine, because once the hype is gone those truly dedicated to making high quality photobooks will continue to do so.

Another sentiment I often run into is that there are “too many bad photobooks.” Occasionally, someone will tell me that there seem to be so many more bad photobooks now than in the past. Of course, that’s true. But it’s really just a numbers game. We all have a good idea what we think is good or bad (even if many of us are reluctant to be honest about that in public). Let’s assume we like maybe 10% of all photobooks. If there are 10 books, we’ll like 1, leaving 9 bad ones. If there are 100 books, we’ll like 10, leaving 90 bad ones. If there are 1,000 books, we’ll like 100, leaving 900 bad ones. Now 900 bad photobooks looks like a lot. But at the same time, there are 100 good ones. So why complain about so many bad ones, when there are also so many good ones?

In many ways, self publishing reflects the overall developments in the photobook scene. I think the percentage of good photobooks that are self published is the same as the percentage produced by commercial publishers. Just like many other people, I appreciate the efforts that go into self publishing a photobook. At the same time, for me the fact that a book is self published does not elevate it beyond those books made by commercial publishers. The only thing I care about is whether a photobook is any good or not. I suppose that’s the one thing I could do without: the idea that somehow the fact that someone self publishes a book adds value to it. It doesn’t. Photobooks are not like cakes where a homemade cake will usually taste much better than one bought at a store.

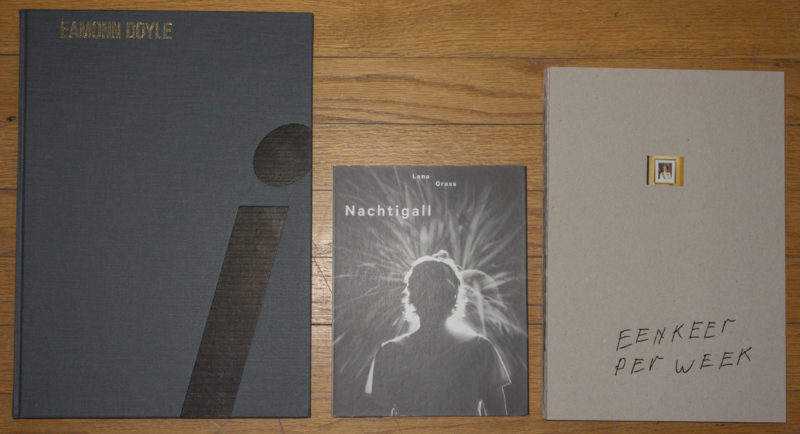

Having said all that, here are three self published photobooks that I think deserve a wider audience.

Eamonn Doyle‘s i is already sold out. That’s good news for the photographer and bad news for anyone interested in buying a copy. I thought about simply not reviewing the book, but then I decided to feature it anyway. After all, books can have a second edition, and if enough people ask for it… Doyle produced 750 copies of the book, a nifty number to sell out, for sure. At the same time, there is no guarantee that a book will sell out, and what do you do with all those boxes of books? Stack them under your bed? To be honest, I have little patience for complaints about edition sizes that supposedly are too small, simply because the economics of making a photobook yourself are daunting. That’s the one aspect where self publishing is at a disadvantage: often, you really only have that one book. How many can you afford to print? If it doesn’t sell enough copies, where/how do you store the unsold ones? And, crucially, how do you offset your financial losses? (You usually don’t, because you can’t – unless you’re independently wealthy.)

i contains street photography, a genre I’m usually not particularly fond of. Let’s be honest, street photography appears to have run its course. But here, the specificity with which Doyle approaches his photographs elevates them beyond the genre’s awfully tired conventions. The compositions are very tight around individual people, most of them elderly (there are a few photos where the subject’s age cannot be inferred). They are photographed from what looks like a bit of a height, which makes them look even more weighed down than they already are by what old age does to the human body. Seen from behind or the side, these people seem oblivious of the fact that there is an observer (or maybe they just don’t care anyway). This approach turns the photographs into an oddly mesmerizing affair, where the viewer feels like they are in fact just a step behind that old man or woman bent over. Most people I know would never be this close to a stranger in the street, especially not an elderly one. Thus, there is a feeling of paranoia seeping in, and it’s the viewer who is feeling paranoid for these people: While essentially watching these people from a short distance, the viewer experiences the feeling of being watched this way. The effect is very unsettling; and I see the book as a very good commentary on both the genre of street photography and on what photography does in general. Ultimately, though, this is a book about life, about how inevitably we will all get old, our bodies will give out, and we’ll die. I really hope there will be a second edition so more people can enjoy this book.

There already is a second edition of Lena Grass‘ Nachtigall available. The first edition of 100 books sold out, so now there’s a second edition of 400 (the second edition comes with a poster). If you go to the photographer’s website you can see a list of bookshops where you can buy your copy; or you can simply email her.

Unlike Doyle’s i, Nachtigall is not an easy book to “get.” Viewed from pretty much any aspect, whether it’s the physical size or the way the photography operates, it’s almost the exact opposite of i. Where i exposes other people in the glaring sun, Nachtigall is a quiet meditation around night and the things that might (or might not) happen at night. Night is the time when you’re lost you really feel it, when the lack of light exposes things that broad daylight would never be able to show. With its simple, understated, yet smart design the book helps the photographs to evoke what they might evoke – no single picture appears to be of any particular importance, but the sum of them all adds up powerfully. This is the kind of book that’s easy to overlook on a table at some book fair (it’s even easier to do that when looking at pictures online), because it requires an engagement that can only be had in the solitude of one’s home.

Niels Blekemolen‘s Een Keer Per Week is part of the photographer’s final exam at an art school in Holland. Much has been written about photobook making there (incl. on this site), so there’s no need to add anything to that. Designed by -SYB-, the book is the kind of smart photobook one can almost expect from Holland, where the art of photobook making has set very high standards, standards that many non-Dutch photobook makers are often struggling to meet.

Een Keer Per Week looks into Dutch nursing homes and the lives of those living there. As a photobook, it’s a very good example of how the general concept, layout, and design can elevate a collection of photographs to something much more than that. The viewer is led into various nursing homes, with more and more details being shown – none of them per se are particularly noteworthy, but that’s exactly the idea. Most of the people living in these facilities only leave them once a week (hence the title, Dutch for “once a week”), so they spend a lot of time in an environment designed to be pleasant, yet struggling with a general lack of resources. It’s the kind of photography project that in principle would be “boring”: what can you take pictures of if there’s nothing exciting? But that’s really where you can find good pictures, because if people have to live in such environments, then the photographs should reflect that. And the book can then do the rest, which it does here.

i; photographs by Eamonn Doyle; 74 pages; self published; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 3.9

Nachtigall; photographs by Lena Grass; essay by Jasmin Seck; 64 pages; self published; 2012 (second edition 2013)

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.5

Een Keer Per Week; photographs by Niels Blekemolen; 140 pages; self published; 2013

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.5

Ratings explained here.