There’s the widespread idea that someone’s suffering might cancel someone else’s. We probably wouldn’t be fighting around 90% of all wars if we didn’t subscribe to this idea as a species. And we might ultimately collectively perish because of it, too (we haven’t yet, but given there appear to be no limits to human folly, there’s no guarantee). Engaging in discussions about this, or even just attempting to, will inevitably result in what I tend to think of as the arithmetic of death, where each amount of suffering is put onto a spectrum, is assigned a value, and the outcome of the discussion then arises from simple numbers: well, their suffering isn’t quite as valid, because, you see, there’s ours, and ours happens to have more weight.

There also exists the idea that someone’s suffering might – really very mysteriously – cancel out or make invalid someone else’s. I personally find all of that very hard to accept. But at the same time, I know that as a human being that is the situation I will have to deal with. I insist, though, that nobody’s suffering cancels out anyone else’s. And I also insist that it is exactly this idea that someone’s suffering is more relevant or important or whatever else than somebody else’s that will perpetuate the circle of violence that has gripped our species. It is not, after all, as if we were somehow doomed to endlessly repeat the cycle of violence and terror that we have inflicted on ourselves (and the rest of the planet). We have a choice. It’s ours to make, and we make it anew every day.

If we think the choice we have is too hard to face, there are ample opportunities for us to try to understand the suffering some people had to endure. Kazuma Obara‘s Silent Histories offers an opportunity to do so. Originally self-published in a very small edition size – each copy was handmade, the Western trade edition of the book was just released. The book deals with the aftermath of the indiscriminate bombing of Japan by the US during World War II, which killed or injured roughly three quarters of a million people.

As those familiar with the history of photography in Japan will know, it’s not the first book to address the suffering of survivors. But with the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki being most prominent in the world of photography so far, Obara focuses on survivors of the other bombing campaign. And unlike artists such as Ken Domon or Shomei Tomatsu, he does so by mostly utilizing other people’s photographs (or materials), making Silent Histories a radical departure in form from books such as Hiroshima Nagasaki Document 1961.

In fact, Silent Histories relies very heavily on archival materials, larger sections of which are included as facsimiles of, say, propaganda magazines, photographs, or ID cards. Production-wise, considerable effort went into the making of the trade edition. How faithful it is to the handmade version I don’t know (and frankly, it doesn’t matter).

In a series of chapters, the book describes the lives of survivors of the bombings. Having lost limbs as young children and living in a society not too kind to the weak, the survivors have had to struggle mentally and physically to get through life. For each, there is introductory text, and then there are photographs, many of them archival, some by Obara. Interspersed is the larger picture, in the form of archival photographs of bombers and destroyed cities, of photographs of contemporary Japan, and of those magazines that were handed out during the war so people could prepare themselves, should they get bombed.

I’m going to be assuming that the usual instincts will kick in, and they might as well. As I noted in the beginning, as a species we have the capacity to empathy and compassion, but they’re not a given. All too often, we decide not to use those facilities, because we’d rather engage in the arithmetic of death. As an artist (photographer, writer, painter, …) all you can hope for is that there will be enough people who might pause, and then enough people who might learn something or decide to change their minds, however hard this might be as one ages. As an artist, I believe, you also have the duty to make those materials available, such as this book, so that people will have that option. This is what Obara has done here. Not more, but certainly not less.

Highly recommended.

Silent Histories; photographs, text, and materials assembled by Kazuma Obara; 162 pages; RM; 2016

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 5.0 – Overall 3.8

Reviewing a photobook will inevitably ask of its author to be aware of her or his own biases or preferences. I cannot speak for other critics, but I personally spend a lot of time on that. The idea is to try to separate out what is in the book from what I bring to it – not that one is more important than the other, though. Instead, there is a balance. There has to be a balance. Reviewing photobooks only on their own terms is a pointless exercise: that’s not criticism, that’s – at best – description. Reviewing photobooks only on its viewer’s terms is equally pointless: that’s just ideology.

Over the past few years, the number of photobooks presenting materials found in some archive has exploded. I’m using the term “archive” in a somewhat loose sense, meaning nothing other than a stash of images that the author has somehow come across. Such an archive could be an actual institutional archive, it could be a collection of images online, or it could be photographs acquired in some way.

Once you have acquired such material you have crossed a bar. But it’s a low bar to cross, especially these days where anything that looks even slightly vintage is automatically considered to be cool or noteworthy. Consequently, I personally don’t think that’s the final bar that needs to be crossed. Instead, I personally want to see something else, something that in the context of US copyright law is referred to as “transformative use”: what exactly do you, the author, bring to the material, lifting it out of the world it is in and bringing it elsewhere. In a courtroom, that’s a problematic term. But in the world of art, it is the central aspect of this all.

To give you an example, if you find a set of cool postcards and you put them into a book, for me the novelty of seeing the material usually quickly wears of. After all, to paraphrase a notion I found in an interview with Richard Hollis, excitement usually isn’t exciting a year or two later. This is especially true in this day and age, where vast parts of the internet operate on presenting something cool or exciting every day (lest we get bored and have to deal with our own, somehow inadequate existences). Let’s face it, how many times will you look at a book containing “boring postcards”? Right, I thought so.

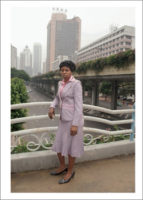

This then brings me to Daniel Traub‘s Little North Road, which features photographs by Wu Yong Fu, Zeng Xian Fang, and Traub. If you’ve never heard of either Wu or Zeng, you needn’t necessarily feel bad. Both work on a bridge in Guangzhou (China), photographing those that come by and are interested in getting photographed. They’re not necessarily the greatest photographers, even though their customers appear to be satisfied.

Of course, there is a story here, given that there are many migrants in the area, coming to look for work. And, you know, that story is interesting, albeit in the sense that most stories are interesting. But Little North Road does little, if anything, to try to do anything other than presenting the story and the pictures, with a focus on migrants from Africa. For me, it doesn’t add up to much beyond that.

Mind you, it’s not a bad book. But what little there is to be discovered reveals itself quickly, and I am not sure there is much of a pull for a repeated viewing. It’s a bit like the stories that you’ll hear on NPR, on your morning or evening commute. They’rejust interesting enough to prevent you from changing the station, allowing you to nod along while you’re stuck in traffic. But ultimately, they’re just infotainment for the slightly better off, guaranteed not to ruffle any feathers.

What feathers could have been ruffled with the material presented in the book I don’t know. That’s not my job as a viewer (or critic) to figure out. But with the flood of interesting material presented as a photobook washing over us, I do think photobook makers operating along those lines need to look for that higher bar to cross.

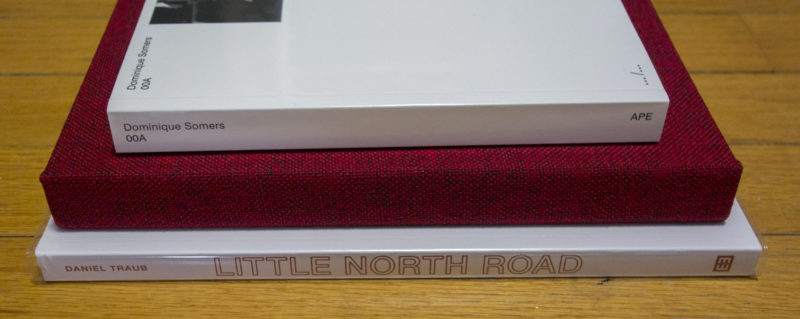

Little Road North; photographs and text by Wu Yong Fu, Zeng Xian Fang, and Daniel Traub; 178 pages; Kehrer; 2015

Rating: Photography 2, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 4.5 – Overall 3.0

In 1972, Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama published a book entitled Bye, Bye Photography, Dear. It was Provoke on steroids, and it’s tempting to think that it demonstrated what that would mean, namely a dead end. Where, after all, can you still go, when you throw out all conventions, when you radically push photography to the extremes?

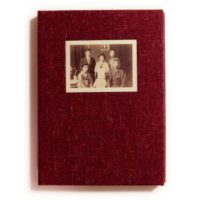

I’d like to see Dominique Somers‘ 00a as a variation on Moriyama’s theme. The book is a collection of the very first frames found on strips of 35mm film, that strange space that perfectly acts like film, but that photographers usually would neglect because you were never sure whether or not there would be a picture. Someone just gave me an old Minox 35EL camera, and I just went through those motions. I put the film into the camera, closed it, and then I advanced the film, having to press the shutter, and again, to have the camera’s exposure counter get to “1” (it never did, since it seems to be broken).

So all of those pictures are 00a ones (technically speaking, on the exposed and developed film there will only be one frame underneath where it says “00a”). They’re pictures of no consequence, pictures that you don’t know whether you’ll get them or not. You might advance the film and press the shutter aiming the camera at nothing, or maybe you’ll just take some picture, not knowing whether you’ll get it after all.

Collecting these kinds of pictures and putting them into a book, as Somers did for 00a, is an act like putting together Bye, Bye Photography, Dear. These non-pictures don’t deserve to be given this kind of attention, but they get it anyway. This replaces Moriyama’s slightly self-indulgent Provoke gesture with a more restrained conceptual approach. Whether ultimately, it amounts to more (or less) I’m not sure. I’m intrigued, though.

Given we’re being flooded with photobooks, many of them following the same few trodden paths, 00a is a book that strays from the crowd. I doubt the book will find many fans – the photographs resist a viewer’s enjoyment too much. But still, the book and the way it is made provide a perfect vehicle for looking at a type of photographs that were eliminated by digital cameras.

00a shows that even in this day and age where it seems everything has been done, you can push the medium photography in imaginative ways. This had had me come back to the book again and again, to find myself repeatedly baffled. What does this amount to? I don’t know. But the not knowing, the not being told that this or that is interesting, the fact that here is an archive that makes so little sense, but that somehow speaks of so much — that makes for a good book.

(The book resists being put into my rating schema, but I’ll apply it regardless – you’ll have to take the overall rating with a grain of salt)

photographs collected by Dominique Somers; 318 pages; Art Paper Editions; 2015

Rating: Photography 1, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4.0 – Overall 2.9

Ratings explained here.