Before getting to business I want to wish everybody visiting this site a hopefully very Happy New Year!

I don’t know how you perceived the year that just ended. I couldn’t help but notice that if there is one thing the populists and neofascists in power in so many countries have achieved, it’s to bring down not just their followers but also the rest of us to a level of nastiness and anger that I feel has contributed widely to 2017 being such a shitty year. As iffy as New Year’s resolutions can get, that’s something I personally want to disengage from. As a first consequence, I will strictly limit my use of and the time I spend on so-called social media, mostly Twitter (I have been off Facebook for year, never looking back). I will only use it to distribute links. If you want to argue with me, send me an email or a postcard.

Over the course of the past few years, I have become more and more weary of social media. This might be in part because this website started out as an old-fashioned blog, which it essentially still is. To follow blogs, you would subscribe — instead of scouring through social-media feeds. Of course, there is a lot to be said for articles being recommended to you by someone whose judgment you trust. But that mechanism has now become embedded in an outright toxic environment dominated by pointless listicles (“The ten German artists that really have you reconsider sausages”), shouting matches and constant outrage over an endless string of scandals and non-scandals, shameless advertizing barely disguised as editorial content, etc. (not to mention the actual fake news, Nazi trolls, and the corporations maintaining social-media sites shredding your privacy).

Obviously, I have no idea how to navigate this online world bypassing social media given that rss — the good old way to disseminate blog content — is all but dead. As a consequence of my 2017 fundraiser, I started writing supporters-only articles, which I send out by email. I have become more and more interested in the idea — reaching possible readers directly. This might entail some form of email newsletter, tailored specifically to only distributing content. There are too many newsletters already, though — do I really need to start one? I haven’t decided whether or how to do it. In the meantime, the easiest way to follow this site is to simply visit it once a week.

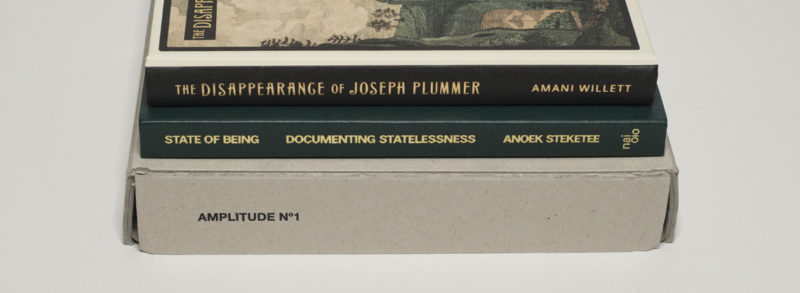

Here are some new books:

“The hermit lived by himself in the woods for 69 years, a result of a childhood desire to be alone.” These words can be found on the reproduction of a small piece of paper in Amani Willett‘s The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer. I don’t know what it is about hermits that has so many photographers curious about them, most famously possibly Alec Soth and his Broken Manual. Actually, I have an idea, but maybe that’s for a later piece. Regardless, the book in question here centers on the idea of a man — and it always is a man, isn’t it? — disappearing in the woods, here first a certain Joseph Plummer and then the photographer’s father who bought himself some land in the middle of nowhere.

The story is told through what of late has become one of the most dominant models of photobook making, using photographs and archival materials of all kinds, blending facts (or what look like facts) with fiction. Thus Joseph Plummer becomes Walter Willett, or Walter Willett is Joseph Plummer, as are any of the countless other men who toy with the idea of really just disappearing, possibly because the weight of the world on their shoulders has become a bit much.

I suppose I should admit that as much as I find the idea of disappearing attractive (at least for a while), my own idea of doing so would certainly not to move into some cabin in the woods. Instead, I prefer disappearings in the middle of hundreds of thousands of other fellow men and women, visiting a larger metropolis in an industrialized country where nobody knows me (I also find the countryside profoundly irritating). But my idea of disappearing is probably at odds with the one pursued by the two men in the book, by the idea of disappearing visually described by Willett. Theirs is romantic. Mine certainly is not. And I rub against the idea of romanticism that is expressed — or at least hinted at — in a variety of ways throughout the book. That’s on me, of course, not on the book’s makers.

Coming back to the way the story is told, through all those different types of photographs and documents (which might or might not be real), one of the challenges is to make the viewer see past the artifice of the storytelling itself. For all its success, Redheaded Peckerwood by Christian Patterson — maybe the seminal book of this kind — suffered from it being a tad too cerebral, a tad too perfect. To make a successful book of this kind you will have to control all aspects — otherwise, the whole thing just falls apart. But, and this is where it gets iffy, if you’re too controlling, it’s very hard to get the degree of uncertainty into the book that makes for the crevices in which the unknown might lurk. “Just as in other forms of art,” Robert Frank wrote about The Americans, “there has [sic!] to be mystery (enigmas) and uncertainty somewhere!” (I’m quoting this from a handwritten note reproduced in Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans).

I don’t know if there are mystery and uncertainty in The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer. But as I noted, this might be just me, given I cannot relate to this type of disappearing. As far as I can tell, the book does what it sets out to do well, possibly a bit too well. At the very least, I wish the photographer had refrained from giving it all away in the afterword.

The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer; photographs and short text by Amani Willett; 136 pages plus tipped in materials; Overlapse; 2017

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.4

Whether as humans we have moved far from the mindset of cave people I don’t know. It’s true, we have our smart phones, and we dress smartly. But the degree of tribalism that dominates our lives is as shocking as it is sad. Not to be a member of any tribe, however, also is no option as Anoek Steketee‘s State of Being: Documenting Statelessness demonstrates. Turns out if you’re stateless, the tribalists turn your life into a pretty hellish affair, with states’ bureaucracies creating the world familiar to anyone who has ever read Franz Kafka (or, to give an example from the real world, has ever dealt with US health insurance).

Typically, you need some document (that you don’t have) to get another one (that you thus won’t get). And that other document (that you won’t get) would help you getting the one that you don’t have. This will be explained to you by some bureaucrat in some anonymous office someplace. And given you’re stateless, there is no tribe that could lend you a hand in the form of a consulate or embassy. You’re literally on your own, and the rules are of course always the rules, regardless of whether they make sense or not. The rules are the rules for their own sake, for their own existence.

Possibly the most infuriating example given in the book is one that reads like little more than a cruel joke. Chisom and Vanessa were both born in The Netherlands, to a mother who had registered as Sudanese but who probably was Nigerian. The mother had got a temporary residence permit, unlike the father who then vanished. Chisom was born prematurely, and the mother died, leaving the two girls as having “no known nationality.” For years, the now young women have attempted to have their status changed to “stateless” (I didn’t even know there was that difference), which would then enable them to apply for Dutch citizenship. And the details keep going from there, literally a series of what can only be described as state-sanctioned cruelty.

“I understand your pain and your despair,” a Dutch judge is quoted as having said, “but I have to act within the legal parameters.” To paraphrase German politician Oskar Lafontaine, that’s the mind set needed to run a concentration camp.

State of Being combines photographs and ample amounts of text to have the viewer/reader get a glimpse of the hellish existence some people have to endure simply because of the kind of tribalism that informs the legal parameters that judge referred to. In light of the fairly large number of similar books that have been produced in Holland over the past decade or two it might be time to speak of the Dutch documentary photobook as a model for how these types of stories can be told, employing a smart and very effective combination of photography, text, design, and production. This book certainly is a very good example.

State of Being: Documenting Statelessness; photographs by Anoek Steketee; text by Arnold van Bruggen and Eefje Blankevoort, 164 pages; nai010; 2017

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

Lastly, there is Amplitude No. 1, published by St. Petersburg’s FotoDepartment, a box set of booklets/pamphlets/zines showcasing the works of ten young Russian photographers: Alexey Bogolepov, Margo Ovcharenko, Irina Ivannikova, Anastasia Tsayder, Igor Samolet, Olya Ivanova, Irina Yulieva, Irina Zadorozhnaia, Anastasia Tailakova, and Yury Gudkov (you can buy the set here). Before seeing the set I was familiar with roughly half of the artists. That doesn’t necessarily mean much, given I don’t consider myself as an expert of what’s going on in the world of photography in Russia. But it hints at the kind of exposure many of these photographers might now be getting, given that their work is being disseminated in this form, with the inclusion of English translations of all the texts clearly aiming at an international audience. Also, seven of the ten artists are female — it would be refreshing to see this approach copied gratuitously in the still so male dominated Western world of photography.

The booklets all follow the same basic parameters, 32 stapled pages with a slightly more substantial cardboard cover that has a photograph attached at the front. In addition, each booklet contains a separate sheet of paper in the back with information about the body of work in question. For me, this type of production makes for a refreshing and appropriate format: there certainly are zine elements, yet at the same time, the pamphlets feel more like a book than a zine. I personally prefer this format over a single book, say, in particular since the separate booklets manage to preserve the individual photographers’ voices.

In terms of the type of photography covered, very roughly there are three somewhat distinct directions. There are bodies of work around Russian villages, there is youth culture, and there is photography around photography (some along the lines of New Formalism). To what extent this selection reflects the larger interests of the Russian photography community I don’t know. Should there be more editions of this type I’m sure we will find out.

For all of those interested in getting more of an idea of what’s going on in the world of emerging Russian photographers, Amplitude No. 1 would be a very good start. The larger world of photography and certainly our Western branch can only gain from being exposed to a wider selection of photography done around the world. And in light of the kind of exposure Russia is getting especially in the West these days — to a large extent of course because of its leader’s shameless power plays, the work of these photographers is a good reminder that there is a lot more to the country than any of the things and events that dominate the news.

Amplitude No. 1; photographs by Alexey Bogolepov, Margo Ovcharenko, Irina Ivannikova, Anastasia Tsayder, Igor Samolet, Olya Ivanova, Irina Yulieva, Irina Zadorozhnaia, Anastasia Tailakova, Yury Gudkov; 10 books of 28 pages each; FotoDepartment; 2017

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.