In many ways, Sébastien Lifshitz‘s Amateur is a shrunken version of Eggleston’s recent Democratic Forest reissue (the multi-volume set). Instead of ten quite large books housed in a slipcase, you get four, the overall size scaled down quite a bit. Every time I pick up the set, I notice its weight first. Even though I have looked at the books quite a bit already, the set still is heftier than expected, literally heftier. There is something to the weight that seems to matter to me. I’m not quite sure what it is.

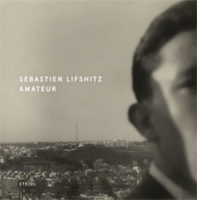

Maybe it is because I associate a certain (metaphorical) lightness with found/vernacular photographs, and the set fights that lightness in more ways than one, beginning with its physical form. But I’m slightly jumping ahead here. So Amateur comprises part of Lifshitz’s collection of found photographs, organized into four separate volumes: Superfreak, Under the Sand, Someone Was Here, and Flou.

Most collectors of found photographs (myself included) organize their treasures using categories, even often looking for specific types of photographs. I wrote about my own hangups with collecting found photographs two years ago. As much as I enjoy finding photographs, whether in the real world or online, I tend to enjoy what other people find more. In those cases because there are two different types of discovery. First, of course there are the photographs in question. Second, there is someone else’s organization or sense of discovery.

In Amateur, you very broadly get photographs of people doing extraordinary things (Superfreak), photographs of people at the beach (Under the Sand), photographs that speak of a human presence (Someone Was Here), and photographs that are either blurry or out of focus (Flou). The summaries of Superfreak and Someone Was Here might sound a bit vague, and they are. I find it a lot harder to succinctly summarize their content than in the other two cases. Perhaps not surprisingly, I’m also drawn a lot more to them than to Under the Sand or Flou. There really is only so much you can get out of pictures of people at a beach or out of blurry photographs. In contrast, there is an overall sense of discovery in Superfreak and Someone Was Here that is supremely exciting, as many different types of images are being connected, are made to be seen together.

All the pictures in Amateur are presented in the same unified way. Whatever the actual photographs as objects might have looked like, that information is excluded. There are no borders visible, no drop shadows. We only get to see the images themselves. I’m a little bit torn about that. I think I might have enjoyed seeing the objects. But then it would also have been a slightly different book, a book of objects, not of images. Removing borders etc. brings the images themselves into better focus, yet at the same time it also amplifies some of the weaknesses in part of the selection. There really are only so many blurry pictures I need to look at.

In a sense, Amateur is the real “democratic forest” of photography, or rather four segments of it. Unlike the case of the one with the capitalized D and Z, this one is the vast repository of photography, assembled by all those unknown amateur photographers. This is the medium’s real democracy, with its pictures being essentially worthless in a monetary sense (quite unlike the capital D/Z ones, sold at the world’s most expensive galleries). As in Eggleston’s case, some organization would have to be performed (compare my pieces about The Democratic Forest: part 1, part 2), and this is, as I noted above, what those who collect do. Just like in Eggleston’s case, this results in mixed results, some of them profoundly rewarding, others less so.

Amateur; found photographs collected and edited by Sébastien Lifshitz; four books in slipcase; 616 pages; Steidl; 2016

(not rated)

Some stories appear to be too weird to be true. For example, there is the story of a man named Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, who was born in Germany, and who then moved to the US, to assume a variety of identities and to, eventually, get convicted of murder. If Wikipedia is to be believed, Gerhartsreiter at various times claimed he was “an actor, director, art collector, a physicist, a ship’s captain, a negotiator of international debt agreements, and an English aristocrat.” How you would get away with claiming to be an English aristocrat when you’re not escapes me. But to a large extent we are not who we are but who we think we are and, crucially, who or what we make others believe we are. Take me, for example. For over a decade, I have fairly convincingly conveyed being a photography critic, even though I’m really just someone with a very advanced degree in theoretical physics. But I digress.

Sara-Lena Maierhofer learned about the Gerhartsreiter case through a newspaper report, and she decided to look into it. I remember reading about it at the time as well. Any German causing any kind of commotion or attention in the US gets a lot of attention in the German press, and the Gerhartsreiter case was just to memorable. Too strange. In some ways, too un-German. A German imposter? In the US? Sure, there were Siegfried and Roy. But that’s entertainment. This case wasn’t entertainment, though. This was serious business.

Maierhofer decided to investigate the story and quickly ran into a conundrum: given all photography is fiction, how to make a fiction about another fiction, a con man’s life? The solution she picked was simple, albeit not obvious: take the ball and run with it. The result, Dear Clark,, is not simple, certainly not obvious, but hugely rewarding (note that the book’s title does indeed include that extra comma). Originally an artist’s book in a relatively small edition, the trade edition, published by Berlin-based Drittel Books, faithfully reproduces all aspects of the earlier version. In particular, this includes tipped-in photographs (underneath, there often are hidden messages). How they did this while keeping the book’s price low I don’t know. But the book would have certainly suffered from being reduced to a version more palpable to commercial publishing.

Much like Gerhartsreiter’s life itself, the starts out in somewhat clear and obvious manner, to then move into all kinds of directions. As can be expected, disguises and appearences feature prominently, with more than one dead end offered up. A viewer looking for a clear-cut story will probably end up being disappointed. But through the various strategies employed in the book, Maierhofer makes it clear that such a clear-cut story does in fact not exist. Or rather, there are markers that tempt the viewer to think there is such a story, a newspaper article here, a photo of Gerhardtsreiter there, but these markers don’t quite connect. Or maybe they do, and Maierhofer simply enjoyed playing the game a bit more. Either way, Dear Clark, successfully takes the form of the photobook as far as it can get right now.

Recommended.

Dear Clark,; photographs and text by Sara-Lena Maierhofer; essay by Marjolijn van Heemstra; 132 pages; Drittel Books; 2016

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.9

Now that photography has become almost fully disembodied, it might not be a surprise that its discarded material properties have become of interest for artists. What previously mostly was just part of the overall process, possibly of the supremely irritating process, has turned into its own fascinating object of study — in much the same way as the objects have. Whether or not this might have us reconsider aspects of Walter Benjamin’s famous essay of works of art in the era of mechanical reproduction is not clear; it certainly might be a better topic for another day, though.

Jaya Pelupessy‘s Set-Put-Run is the latest example of work around these ideas. In this case, the form and concept of the book itself is made to tie in with the work’s — as, obviously, it should, regardless of what subject matter we’re actually dealing with. But this is really no given in today’s hypersaturated photobook market, where often enough, books are produced quickly for effect (and inclusion in any of those shortlists).

Here, we needn’t worry, since the book was produced by FW:Photography, designer Hans Gremmen’s company. For me, this is one of the most inspiring photobook publishing houses these days. Gremmen’s output has been consistently challenging, even in cases, as this one, where the photographs in question might have left me cold, had I encountered them in a mere catalog or as prints on some wall. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to see Gremmen “in action,” as part of a workshop on photobook making. To be honest, it’s a humbling experience, given his approach and thinking about photobooks are so focused on finding the right form, while avoiding anything unnecessary.

Set-Put-Run revolves around the idea of taking photographs and of giving them a physical form (or maybe container — of which a book clearly is one example). It’s “meta” in the purest sense — this book is about photography itself. Consequently, looking at the book makes for a very cerebral experience. While I have my own preferences for what photography I might prefer, I will admit that as much as “meta” photography can irritate me quite a bit, if it’s done well I enjoy looking at it. In other words, I am open to a wide range of experiences offered by photography. This is clearly the case here.

To be more specific, I enjoy seeing the ideas behind the work unfold in front of me through the way they’re given shape and form in this book. Admittedly, part of my enjoyment might come from having looked at many books, seeing how they were put together and made. Seeing one that works well always is a bit like seeing a particularly poignant solution to a mathematical puzzle — there is an elegance to it that I can’t fail to appreciate.

Set-Put-Run; photographs by Jaya Pelupessy; essay by Simon Winchester; 128 pages; FW:Photography; 2016

Rating: Photography 2.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.4

Ratings explained here.