We’ve become an inward-looking culture, having replaced a constantly maintained general interest in the larger world with occasional and then usually very frantic bursts of attentiveness. Photography reflects this shift very well, in all kinds of ways. So-called “selfies” have become a hot phenomenon. Visual and occasionally literal high-drama images are now being delivered via sites like Instagram from all over the world, courtesy of mainstream magazines or websites obsessed less with quality of content than with speed of delivery.

In the area of fine-art photography, family photography has become incredibly popular. It’s very hard not to feel a little funny about the large number of family-centered photography projects coming out of art schools, for example.

On the other hand, family does provide a rich ground of exploration if – and only if – it is well done. As solipsistic as we have become in this Age of Facebook, there are those who came before us, and then there are those who came after us. So maybe the saving grace of family photography is that, by construction, it contains the seed of something much larger, something that exists far beyond one’s own navel.

I’m thus tempted to think that for family photography to work well, it also to acknowledge, in whatever ways, that there is a world out there, a world from which a family, any family, is not hermetically sealed. The following three books each navigate this terrain in different ways, offering insights into what can be gained from looking at those closest to us.

If anyone knows that there is a world out there it’s Christopher Anderson. As a photojournalist, Anderson traveled to some of the most dangerous places, risking his own life to get pictures. I can’t help but think that it is exactly that past that has made Son what it is. The sense of wonder witnessing the birth of a child or the sense of dread seeing a father being very sick – these are probably universal feelings. But someone used to going out into the world to find such drama elsewhere can’t help but bring a different sensibility to the table.

It would be so easy to imagine that when you have witnessed the most horrible things elsewhere anything at home would pale in comparison. But the opposite appears to be true. Or maybe it’s not quite the opposite but the realization (however subconscious it might be) that there is a relevance to those things that only concern such a small number of people, the little family, that there is wonder in the smallest things at home. It is that sense of wonder that had Anderson take these photographs, some of which possess an almost childlike appreciation of the world in front of the camera (and I mean this as a compliment).

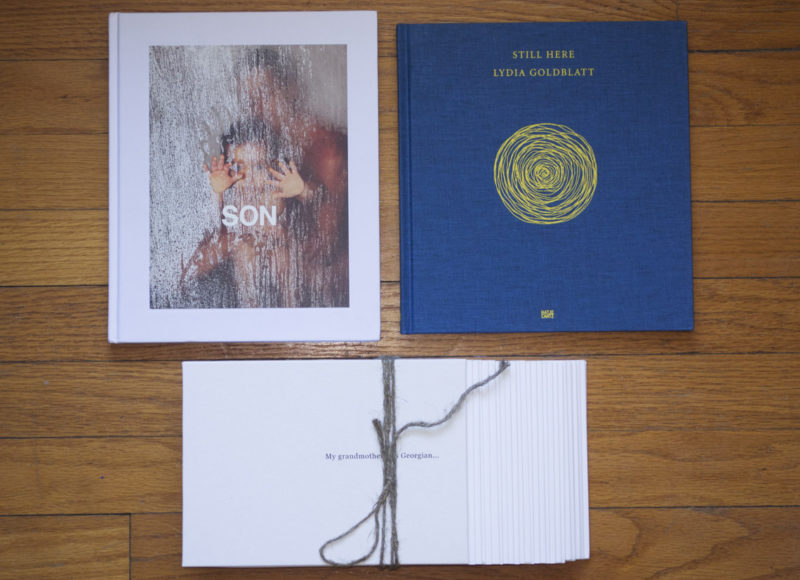

Jana Romanova‘s Shvilishvili is a very different kind of book. Presented in hand-made accordion form, it focuses on two aspects of the photographer’s family. There are the connections between people, someone related to someone else who, in turn, is then related to someone else etc. These connections are shown photographically using group portraits, the presence of people in pairs of pictures providing the visual clues for what’s going on. With the subjects living in Russia and Georgia, the world and the things that world will do to people are right there: Families often transcend borders or cultures, and the strain caused by those can be immense.

In the second part of Shvilishvili (remember, accordion books have two sides), Romanova attempts to understand her grandmother’s life through reproductions of photographs and a few ephemera (the book includes some actual objects, which adds a wonderful touch to the experience). Ultimately, there is no way you could ever come to terms with or understand your family, however hard you might try. Any approach inevitably has its shortcomings, photography being too literal, while revealing too little. But it is exactly this that makes this book succeed: One can almost feel the effort that went into its making, driving home the point that without this desire to know and understand (and the ultimate futility of the endeavour) there is no such thing as family.

Lydia Goldblatt‘s Still Here is the most lyrical and understated of the three books, solving photography’s inability to do certain things by working around them. You cannot will photographs to show everything you want them to show, however hard you try, so you might as well release them from that burden. This realization makes a photographer’s position precarious, but it also opens up a world of possibilities, many of them on display in this gorgeous little book.

Goldblatt employs the full range of what can be done with photographs in a photobook, using individual photographs, pairs and short sequences, and, crucially, trusting that her pictures would somehow convey everything they needed to convey (well, almost – I would have preferred the book without any of the added text; I’m sure many people will disagree). The photographs show what is (or actually was) there – the father, they mother. But also make clear that as such, they mostly reflect our desires for things not to change, for things to remain as they are. But they won’t, and that’s ultimately fine. Still Here is a meditation on why that’s fine, why denying that there is a beginning and an end will not provide a way out.

In the end, family is a riddle that cannot be solved, that can only be approached. These three artists each approach this riddle in their own ways, creating three very distinct photobooks, each of which avoids the various pitfalls of the genre easily.

Son; photographs by Christopher Anderson; 96 pages; Kehrer; 2013

Shvilishvili; photographs by Jana Romanova; 106 pages (accordion); self-published/artist book; 2013

Still Here; photographs and essay by Lydia Goldblatt; essay by Christiane Monarchi; 88 pages; Hatje Cantz; 2013

Ratings explained here.