If there weren’t so much at stake, the spectacle of politics would be quite amusing. After all, here we have a group of people that often not only are shockingly uninformed, but that usually are very much disconnected from the reality most people have to deal with on a daily basis. The one thing politicians have come to understand very well, though, is that their image matters, resulting in a literal spectacle that once you take it apart becomes almost mind-boggling.

Journalists are supposed to inform the public about politics. In principle, this would be an easy job, if it weren’t for the fact that things are not quite so simple. For a start, you need to get the access. No access, no information. No information, no report. No report, no job. That’s a bit of a problem. Thus in reality, the relationship between journalists and politicians is quite a bit more symbiotic than what you would imagine in an ideal world. More often than not, journalism – whether by design or simply out of sheer necessity – has to if not enable then at least not subvert the spectacle that is politics. Nobody really seems to mind about this arrangement – as long as someone will occasionally fall out of favour and can then get the treatment all politicians possibly deserve.

The only occasions where the spectacle of politics might slip happen during election campaigns. There usually is so much going on during a campaign, with so many speeches to be given here and there, that even the tightest control over a campaign is unable to prevent the occasional mishap. Most of those mishaps are very minor, but they offer revealing insight into the spectacle itself. Usually, one of the mishaps is pounced upon by everybody, to then become the defining moment of the campaign.

It’s almost as if there is a gentleman’s agreement (remember, politics still is dominated by men): journalists report the spectacle faithfully, not attempting to subvert the game, but the slips are fair game.

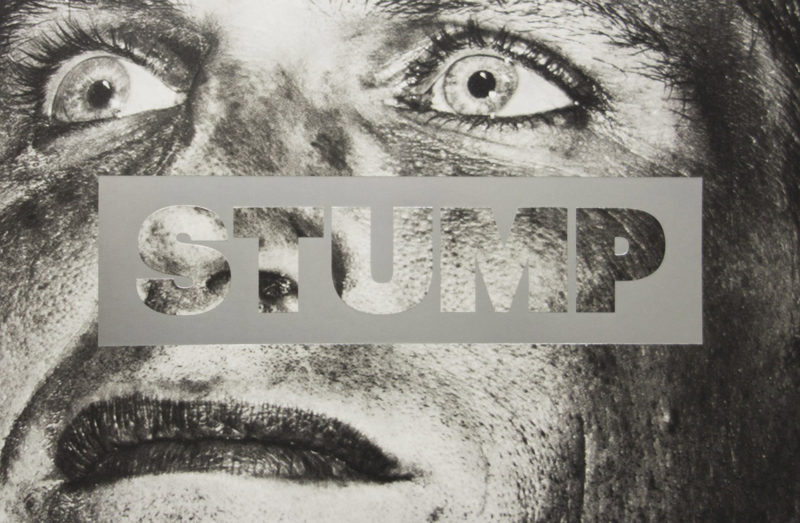

With Stump, Christopher Anderson is having none of that. Here, those involved in the game, running for some office or otherwise participating in a campaign, are put on display in possibly the most obvious and at the same time crudest possible way. It’s almost as if the photographer is telling politicians that if they expect to be put on a pedestal, he will put them on a pedestal alright. With a few exceptions, the book is filled with portraits, all of them framed very tightly and closely, exposing whatever there possibly can be exposed in someone’s face. Let me just say that nobody looks very good when Chris Anderson trains his camera on their face this way.

So yes, that’s a very crude device, which is guaranteed to ruffle some feathers, even in circles that might consider themselves to be critical of the whole visual spectacle of politics. We aren’t really dealing with a group of saints here, though. And crucially, the book seems more like a reflection on the spectacle itself and on journalists mostly playing along, often somewhat meekly fulfilling their role.

There’s a fearlessness to the enterprise that I really appreciate. As a result, even though many of the photographs aren’t even very good photographs per se, violating possibly every rule photographers have come to accept, the whole package not only works very well, but also provides an extremely guilty pleasure. This is the spectacle we have gotten so used to, a spectacle we almost seem to be expecting. Consequently, why not have the man behind the curtain – that we are all so aware of – turn the cranks even faster, to provide us with even more spectacle – until we can’t stand it any longer?

Stump; photographs by Christopher Anderson; essay by John Heilemann; 96 pages; RM; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.