Ever since Marcel Duchamp presented a urinal as a piece of art in 1917, the question what art is has become meaningless. If a urinal can be art, anything can be art, including (obviously) photography. The discussions around whether photography is art are interesting not because they tell us something about the medium. Instead, they speak of what the people involved in such discussions consider art.

Unfortunately, photographers have been pretty bad at playing the game. Instead of happily embracing their medium and its many possibilities, more often than not they instead accepted other artists’ criteria for what their photographs had to look like for them to be considered as art. This gave us abominations such as Pictorialism, a form of visual shlock that because of its sheer triteness is almost interesting. Almost.

We might as well ask the following instead. What exactly can photography do that other art forms can’t (or what they might be bad at or at an advantage at)? After all, we celebrate painting for what it can do, we celebrate sculpture for what it can do — why don’t we do the same with photography?

Well, you might note, what about the people that I so callously refer to as the Neoliberal Realists (Andreas Gursky et al.)? Montaging photographs from constituent parts and then presenting them as if they were paintings — even as I happily accept these photographs as photographs, I don’t think borrowing so many techniques from other art forms is necessarily an expression of confidence in one’s own medium.

What I’m after here is something altogether more simple, something that is so obvious that I don’t think many people realize what a radical gesture is associated with it. It seems to me that if photography brings anything to art, it’s the ability to employ repetition to great effect. In fact, if used well, the end result of repetition can result in one of art’s most important themes, the sublime. I call this the repetitive sublime, the effect of which is achieved through sheer repetition and variation.

“Badacsony,” Wikipedia tells me, “is the name of a region on the north shore of Lake Balaton in western Hungary, a mountain top and a town in that region.” It’s also the name of a book by Ábel Szalontai.

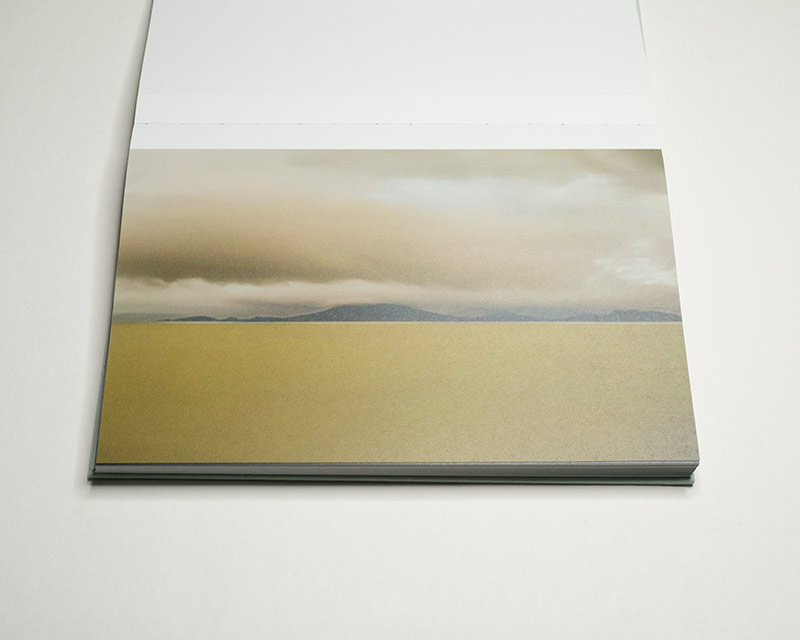

The Wikipedia page comes with a photograph that shows an expanse of water — the lake, with a prominent mountain that features an oddly flat top behind it. There appear to be buildings near the mountain. On Google Maps, there is a settlement on the other side of the lake (Fonyód) that’s closest to the mountain. I check a number of random places using the “Street View” option and find the mountain across the lake in the background of the pictures.

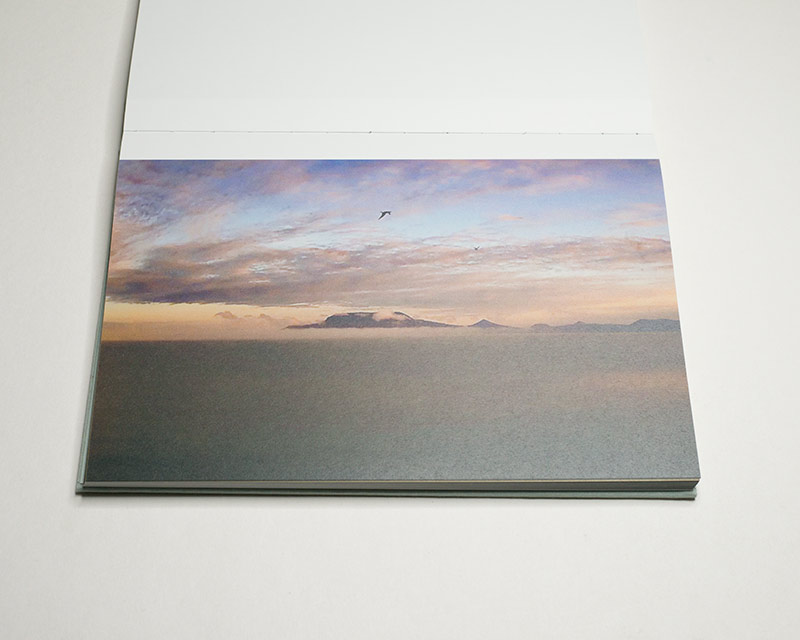

If you grew up by the sea (as I have), you know of its magic. The sea is always the same — a field of water; and yet it is always different. There is something about larger bodies of water than enhances the senses and that even if you’re not a photographer makes you notice everything, especially the quality of light.

Faced with a vast body of water — an ocean — you’re likely to experience the sublime in its most well-known incarnation, especially if there is a storm brewing on the horizon. There is something incredibly vulgar about how uncaring the water is for your own concerns (or safety).

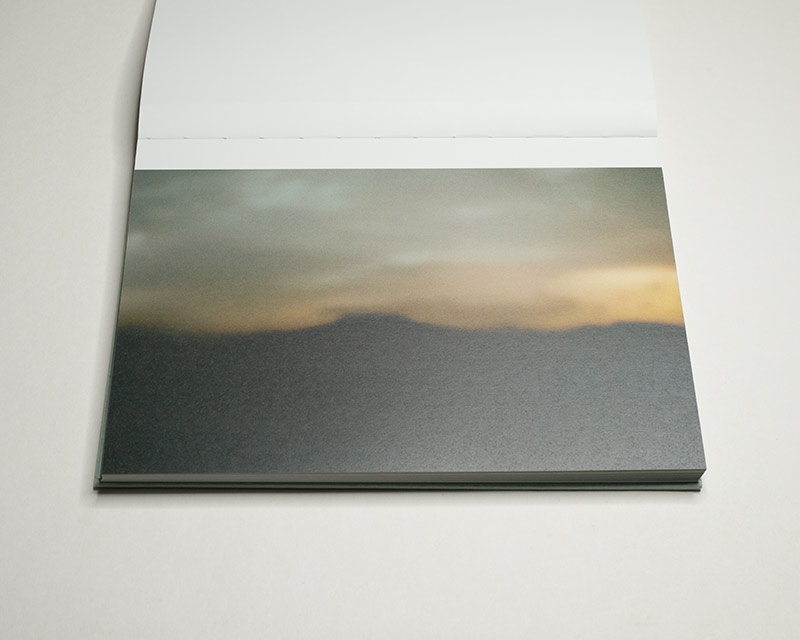

In Badacsony, you encounter the very same view towards that flat-topped mountain many times. There is the same stretch of the Lake. Each view is exactly the same, and each view is completely different as the time of day and weather change. I’m imagining that this might be the view from some building, and I’m imagining being the person whose view I am presented with.

It is their combination that creates its effect, reminding me of the fact that like every other human being I am merely a temporary visitor on this planet. Each moment that passes brings me closer to my own demise. Each moment that I spend on, for example, pressing down combinations of letters on my keyboard amounts to time deducted from an unknowable total.

This is the repetitive sublime that photography can deliver: through sheer repetition, by presenting the same picture in any number of variations, photography can make us face the insignificance of our existence.

I wrote earlier that other forms of art are unable to do it. That’s not fully correct. A completely different medium, music, can achieve the same effect. I’m thinking of, for example, France, a three-person band (you might be able to guess where they’re from) whose performances are a single drone. As the drums and bass lay down the rhythm, an amplified hurdy-gurdy produces an initially bewildering and ultimately mesmerizing sound that doesn’t appear to end. You can only understand it if you experience it in its entirety — this 71 minute track is the best I have found so far.

Of course, France‘s music is not the same as what photography does with its repetitive sublime. Listening to France will put you into a meditative trance in which the minutest variations in the sounds take on vast importance and in which a single medieval instrument somehow transforms into an occasionally terrifying orchestra. This will make you forget about time and have you face your innermost fears.

Given the fact that as viewers, we control the speed with which we’re looking at the pictures, photography does not throw you into a cauldron that is being stirred by outside forces. Instead, it layers picture upon picture upon picture, to achieve a similar effect: while as a viewer you’re the one who is doing the stirring, you will still have to face the fact that for this world of mountains and seas and plains and all of their creatures you are nothing. What you encounter in front of you is infinitely more complex than anything you’d ever be able to understand.

Why would you look at this, though? Or why would you listen to 71 minutes of France? There’s a simple answer: doing so is awe inducing in the most basic sense.

As for the book, I could have done without the selected parts of Laura Iancu’s poem alongside the pictures. But the words are easy to ignore when looking (you can later read the full poem in the back).

Recommended.

Badacsony; photographs by Ábel Szalontai; essays by Krisztina Somogyi, J.A. Tillmann, Laura Iancu; 182 pages; Self-published; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!