Over the course of its history, photography has been serving oppressors and liberators equally. The machine doesn’t care what it is being used for. Seen that way, it finds its place in the history of what think of as progress: that long march towards a future governed by technology, technocrats, and scientific advancements.

All over the world, we can see photographs being made and used in the context of struggles. In the US, bystanders film a group of cops as they murder an unarmed Black man while the cops’ own “body cameras” record the very same act — as do various surveillance cameras in the neighbourhood. Very similar scenes play out in Belarus, as protestors voice their disapproval of its country’s dictator having stolen the last election. They record while they’re being recorded. Anywhere you move on the globe you now encounter the very same setup.

Time and again, we witness how the presence or absence of photographs is not the deciding factor that determines the outcome of a struggle. Derek Chauvin was sentenced for the murder of George Floyd, but the list of police officers who got away with similar killings is too long to list here. What we’re talking about here thus must not be centred on photography: it must be centred on everything that comes before — the larger environment pictures are being produced in — and on everything that comes after — the environment in which the fight over what constitutes truth plays out.

Consequently, it is naive to expect of photographs to change the world, actually to change anything for that matter. The presence of a picture cannot compared to the presence of, let’s say, a vaccine against Covid that will protect you from getting very ill. Vaccines produce antibodies. Photographs produce nothing.

Still, photographs are very important in the process of a struggle. They strongly express the conditions in which the struggle plays out, and they shine a light (albeit a weak one) on the conversations that are being had around the struggle. This might not seem like much. But I would argue that because of this, photography actually has a lot more power than we think it has — it’s just not the power to change the world (that’s up to us).

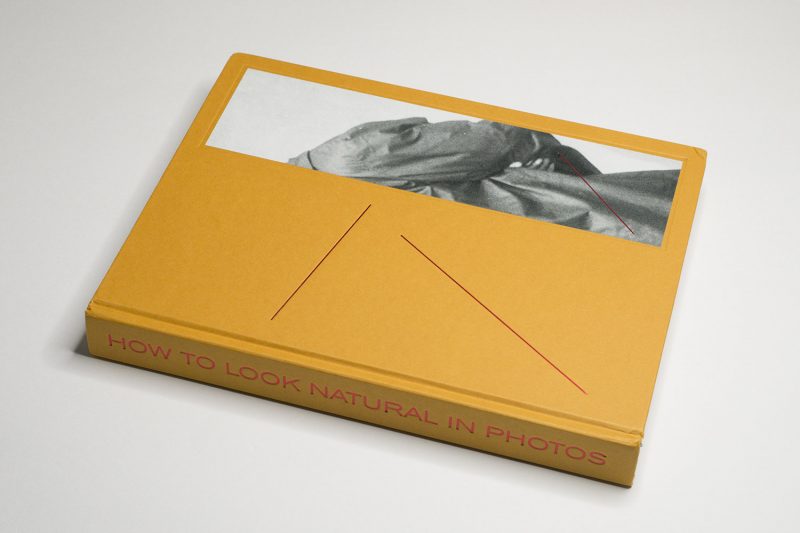

I want to use a recent publication of photographs taken from the archives of the Communist regime in Poland, now housed in the Institute of National Remembrance, as an example. The publication is called How to Look Natural in Photos, and it was edited by Beata Bartecka and Łukasz Rusznica.

It’s a book that comes with the temptation to treat it as if it were about the past, in this case the totalitarian regime in Poland. It is possible to look at the book and shake one’s head about the evils of Communist Poland’s secret service. But it also is a book about the present, especially in light of the country’s far-right government’s various mechanisms to politicise memory to create a very specific idea of what Poland was and is (and, crucially, is not). The archive, in other words, is not entirely innocent, given the government is working very hard on reframing the country’s history.

But I’d go even further and claim that the book is not just about Poland at all. What is depicted might have happened in Poland, but it speaks of the uses and abuses of photography by those in power in general: this is a book about the violence committed by and with photography, a violence that the medium derives from the violence of those in whose employ it is.

Photography’s violence is always inherited or transferred: the violence is never one of the medium per se, it’s the violence of its use. A camera, after all, is merely a tool that can be used in a variety of ways — whether to contribute to an exercise of violence or to fight against such violence (please note that with “violence” I mean both physical and structural violence).

As one might expect from a secret-service archive, the photographs in How to Look Natural in Photos are functional and evidentiary. They were not made to be anything else. Consequently, where there is beauty in them, that beauty is accidental. Where they strike the viewer as funny, that is accidental. Where they are grim, that is accidental, too.

I would argue that the key to working with such state archives is to find a way to reveal the (structural) state violence that expresses itself in the pictures. After all, focusing only on the beautiful or funny or grim already deflects from the complexity of the violence that produced the pictures. But such an approach also shields existing state structures from being indirectly exposed. There could always be the deflection: “sure, but these pictures are from Poland, so what does this have to do with us?”

I suspect that deflection might always be invoked. But anyone interested in looking at how photography can reflect state power will find rich fodder in the book. Given there is no text next to the pictures, they operate in much the same fashion as in the now classical model established by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel. Anyone interested in learning more about the pictures will find the index useful. Furthermore, there is a detailed essay by Tomasz Stempowski about the photography in its own context.

Anyone looking through the book might want to ask themselves what contemporary equivalents are being made right now, wherever they might live, how, in other words, their own state exercises its power.

It’s much too simplistic to insist on differences between democracies and dictatorships, when underneath the hood, state apparatuses have a lot more in common than we would like to think. If a citizen gets killed by the police without subsequent accountability, it doesn’t matter much whether we’re dealing with a democracy or a dictatorship. This is not to fully equate democracies with dictatorships; the difference is that in a democracy, its citizens can demand accountability.

So for those living in a democracy and wishing to maintain it, there’s work to do. It’s a lot of work, and it requires a lot of time. Democracies need to be maintained by its citizens.

Maintaining a democracy entails looking at how power is exercised by those who were either elected or who got a job that comes with power: how are they using photography? What does their use of photography and their way of dealing with photographs express about how they view their own power? This can easily get one into uncomfortable territory.

But democracy cannot be defended from the comfort of one’s own (privileged) position. It must be defended actively, and that defence includes making pictures as much as looking at pictures made by the powerful. This is why and how photography matters.

Recommended.

How to Look Natural in Photos; photographs from the Polish Institute of National Remembrance, edited by Beata Bartecka and Łukasz Rusznica; 304 pages; Palm* Studios & Ośrodek Postaw Twórczych; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article about photobooks, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.