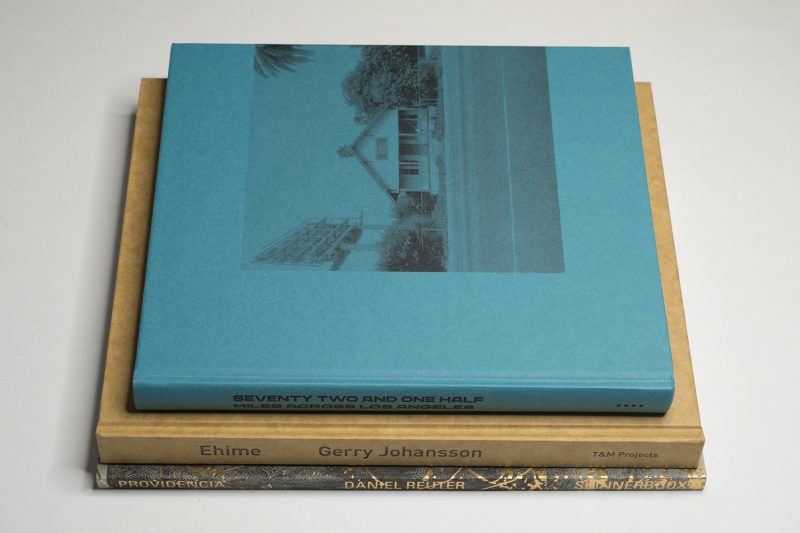

In 1999, Gerry Johansson spent four weeks in Japan’s Ehime prefecture, which covers the western part of the Shikoku Island and lies directly to the south of Hiroshima. His trip had been financed by a grant that would bring European photographers to Japan, to make work there. The resulting photographs have now been published as Ehime by T&M Projects.

Johansson is mostly known for his work with the square format (over the years, I have reviewed a number of books containing such pictures — you can find them through my index of photobook reviews). But there also was an earlier book with pictures made in Japan, specifically in Tokyo. Using an 8×10 camera, he had scoured the Japanese capital’s cityscape, focusing mostly on the many brand new buildings there (as a city, Tokyo is constantly in flux as older buildings get torn down, to be replaced by newer ones).

I remember that the Tokyo pictures had left me cold. They were very good pictures, but the surfaces and shapes of the buildings had reduced them to be more or less exercises in form. This is good, if that’s your thing (I personally find it mostly tedious). But focusing on just form eliminated the bulk of what makes Johansson such an interesting photographer when working with the square: the visual wit.

When I first went to Tokyo, I noticed how off putting I ended up finding many of those shiny new areas: they’re not only not very good in front of one’s camera, they simply lack all soul. But it’s a problem even outside of Tokyo. Japan has invested an enormous amount of money into its infrastructure, which has resulted in a lot of areas being covered with all kinds of concrete structures to hold them into place. There are these structures that just beg for formal treatment everywhere.

As a body of work, Ehime is another animal that sits somewhere in between Tokyo and most of the square work. By its very nature, an 8×10 camera has a very strong pull towards formal considerations. It’s such a hassle to set up and you can spend so much time studying a picture on the ground glass that all humanity might simply evaporate. While this happens occasionally in the new book, for the most part Johansson was able to evade the problem.

There are many pictures of neatly organised built structures and neatly pruned trees of bushes. But there are also many pictures of locations that at least at the time had not been reached by concrete mixers and construction crews, yet.

In a sense, the Japan that is described in these pictures is one that resist easy categorisation or description. It is that aspect that I appreciate the most. In some ways, anything you might expect is there; but it’s there in a way that doesn’t merely confirm, while presenting itself in a visually engaging and pleasing manner. And all of this comes in a very elegant and nicely produced book.

Recommended.

Ehime; photographs by Gerry Johansson; 184 pages; T&M Projects; 2020

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 3.9

One of the defining feature of much of contemporary photography is that it holds its viewers at arm’s length. This works really well for a lot of work. But with it being so widely used, the accumulation of all of these arm’s lengths also has created an overall atmosphere that is a bit too detached. Over the years, I have become increasingly sensitive to this issue. This is not to say that I now prefer work that is in my face (which only creates a different form of tedium). Instead, I tend to look for modulation, for a push and pull. I couldn’t say how this push and pull might work; in fact there might be no universal “recipe” for it.

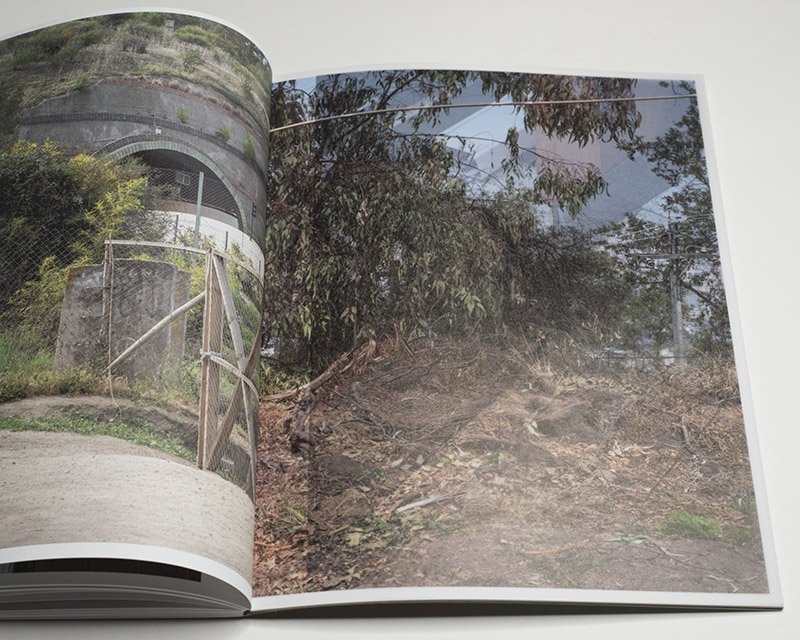

I had think about all of this again when looking at Daniel Reuter‘s Providencia. According to the publisher’s website, the book was edited and sequenced by Milo Montelli. Thus, there is another pair of eyes and hands at play here. In addition, the book employs a few production tricks, such as, most prominently, the use of vellum paper upon which photographs are printed. These pages allow for the images on the neighbouring pages to shine through.

Photographed in Chile (in one image, the word “Chile” can be clearly read on the license plate of a car), these pictures could have been taken anywhere where the promises of late capitalism have just reached their tipping point: the beauty of the eventual outcome has just been revealed as hollow, the rising tide is not at all lifting all boats, and the next essentially man-made and entirely prevantable disaster is just one freak meteorological event away.

There are many surfaces in the book, too many actually: rocks and the sides of buildings and semi-translucent windows and gaudy plastic coverings. There are landscapes, too, some arid, some lush yet equally uninviting. And there are a few pictures of people, none of whom look at the camera, all trapped in their own thoughts.

I don’t know what’s missing. But I feel as if something were missing: a counterpoint of sorts, that rare opening where as a viewer you can move closer in, however briefly. Ultimately, the book makes it clear that there is a promise that is being betrayed. But its own shrinking away from giving a glimpse of what that might mean has been leaving me in a position where I’d like to care a little bit more about this place. And yet I don’t.

Maybe that’s the idea. If it is, then it’s done successfully. If it is, though, then for me, that’s not quite enough (as usual, your mileage might vary). If it is not, if the book wants me to care about the lives of all those people living in a place (why else would I look at it?), then I think I need to be offered very slightly more: an opening, a crack (metaphorically, I’m not speaking of the many literal cracks displayed in the pictures), a glimpse not of the promise but instead of what that promise has done with people, done for people.

People want to believe. In a photobook, I’d like to believe with them, even if it’s just for a moment. But maybe that’s something that contemporary photography operating at arm’s length simply cannot offer. Or maybe this is just me getting old. If it is that, though, me getting old, then I actually quite like that it does this to me: pulling me away from pure judgment, from cynicism, and wanting me to go to the inside of those arms.

Providencia; photographs by Daniel Reuter; essay by Alejandro Zambra; 112 pages; Skinnerboox; 2020

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 3.8

I have the theory that basically every city is good only for certain people, and I know that Los Angeles is not for me. To begin with, I find riding in or driving a car awful. So a city organised (if that’s even the right word for it) around having to drive everywhere is farthest from the kind of place I tend to enjoy.

Obviously, you don’t actually have to drive in Los Angeles, you could just walk. Fair enough. But then walking in a place that is organised around driving also is not very enjoyable. Still, some people do it, such as, for example, Nigel Raab who walked 72.5 miles across the city in four days. Raab then approached Mark Ruwedel and asked whether he would be interested in making pictures along the route. Ruwedel was (he used a car), which eventually resulted in Seventy Two And One Half Miles Across Los Angeles.

In the world of astronomy, one would describe the outcome of the exercise as a pencil-beam survey: a narrow, yet deep look at a small, selected part of the Universe that despite its restrictions still offers possibly a lot of interesting results. Raab’s route across Los Angeles follows a similar idea, as becomes clear from Ruwedel’s photographs. As much as there is ample repetition — the same types of houses, the sheer endless expanses covered with roads — there is a progression that, I suspect, someone familiar with the place would be able to pick up on even more easily than an outsider like me.

In some ways, the book itself reminded me of especially technical books from before I was born. I don’t know enough about typefaces to know better — or maybe the connection was made on purpose. But I appreciate this aspect of the book. This also includes the placement of the photographs on the pages, with those of their edges closest to the fore-edge always touching it: the design invokes the idea of something continuing, even though unlike in some contemporary Dutch design parts of the same picture are not printed on the obverse and reverse of a page.

What I’m going to take away from the book other than confirmation that this place indeed is not for me I don’t know. But I appreciate that challenge in a book: it makes me look again and again, to see whether I’m not in fact missing something. After all, I might. There also is that connection with the tradition of art/photography made in Los Angeles (hard not to think of echoes of Ed Ruscha), a connection that reminds me of how there’s an underexplored spot in my own way of looking at photography made in the US.

Seventy Two And One Half Miles Across Los Angeles; photographs by Mark Ruwedel; texts by Nigel Raab and Mark Ruwedel; 160 pages; Mack; 2020

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 3.7

Ratings explained here.