All art is political. I gets iffy once artists attempt to produce something explicitly political. More often than not, the result is what I would think of as agitprop: political propaganda. Why that is a problem ought to be obvious, given what politics means: there is no such thing as solipsistic politics. You can’t have a political argument with yourself. So if politics always involves other people, as art does, then adding an explicit element of persuasion to it — which usually seems to be the idea behind “political art” — tends to tilt the balance towards crude propaganda.

These days, most photographers prefer not to be openly political. It’s just easier that way to deal with the intricacies of the world of photography (and beyond): you just never know where the wind might be blowing next. Plus, if you have a vested interest in selling your photographs in commercial galleries, it takes guts to bite the (rich) hand that feeds you. So the number of artists who will be happy to discuss politics in their work is relatively small. Which is, to make this very clear, fine with me. I certainly don’t think it’s up to me to decide how overtly political a photographer needs to be. As I said, all art is political, and an interest in keeping your politics seemingly under wraps speaks just as loudly as open political commentary.

If someone asked me for the names of political artists/photographers, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin would probably be the first names that would come to my mind. I’m not sure to what extent this is based on my own ideas of what political art ought to be or do. For sure, it can’t be completely independent of them. To some degree, I’ve always tied this pair to a tradition of political art that has strong connections to ideas pursued during the heydays of the ill-fated Weimar Republic.

Arguably, this very short period of time and locale produced some of the most influential ideas and photographs, ranging from August Sander‘s portrait of the German people (which, granted, is deeply rooted in an older time, but which also would not have blossomed without the freedom accorded by the Weimar Republic) to Bertolt Brecht‘s alienation effect to Otto Dix‘s and George Grosz‘s painted challenges for photography to László Moholy-Nagy‘s exploration of and blueprint for photography to John Heartfield‘s political montages to Hannah Höch‘s groundbreaking work (my favourite parts are the collages) to Walter Benjamin‘s and Siegfried Kracauer‘s cultural criticism etc.

You have little bits and pieces of almost all of these artists and writers in Broomberg and Chanarin’s work, some more prominent than others. The maybe most obvious example would be provided by War Primer 2, their re-mix of Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 Kriegsfibel. With its collection of re-purposed (art lingo: appropriated) press images and clippings, Brecht, ever the trendsetter, was a few decades ahead of what ultimately would become a very important (and hotly contested) trend in art. War Primer 2 was originally published in an edition of 100 and and it sold out rapidly (who says you can’t produce critical political art and cater to the select few at the same time?). But there now is a softcover re-issue available.

And the book is good in the sense of being, well, good. Brecht’s original book didn’t need any improvements or updates. That said, the idea of taking contemporary imagery and adding it on top of the earlier imagery was obviously up for grabs. Beyond the appropriation aspects, though, it’s not clear to me what exactly one would learn from that exercise other than war is bad and politicians will do evil things. Brecht already told you and showed you that, and Brecht’s appropriation of imagery for me looks like a much more radical gesture than Broomberg and Chanarin’s added material. Your mileage might vary.

I think that’s one of the hidden pitfalls of political art: given so many artists are only too happy not to talk about politics, the moment you produce something overtly political that’s already a radical gesture. And discussions around whether the results are any good always get drowned out by the chatter around the politics. This must make it hard to actually produce political art these days: where and how would you get honest feedback? The couple got a Deutsche Börse Prize for the book (speak about tainted money!), but that prize appears to lately have been handed out mostly on the basis of the perceived intent rather than the actual artistic quality of the work.

Anyway, back to the Germans. I first became aware of Klaus Staeck while being in high school. I wasn’t aware of this then, but now I know that Staeck followed the tradition of George Heartfield, making political posters that were assembled from re-purposed imagery, with often pithy and biting words added. For me, there’s something quintessential West German about the artist, even though I wouldn’t know how to justify the statement other than saying that Staeck provided one pole of the visual universe that deeply embedded itself in my brain. The other, opposite, pole was seeing the “Wanted” posters for West Germany’s left-wing terrorist groups in post offices and other official buildings. Well, there’s a rabbit hole I just became aware of, namely how my visual thinking was so deeply influenced by both an artist and the government re-purposing photographs.

The full trajectory of Staeck’s career is laid out beautifully in Sand fürs Getriebe, a catalog produced at the occasion of an exhibition at Essen’s Museum Folkwang. I had never seen the woodcuts before, and the somewhat Warholian early screen prints I was only vaguely familiar with. The bulk of the book is provided by the posters, which, as I noted, bring back strong and not necessarily altogether pleasant memories of West Germany, specifically the period of time called die bleierne Zeit (the leaden time), when West Germany’s technocratic Chancellor was engaged in a stand off with said terrorists, and the early years of the Kohl era, which eventually became (mostly West) Germany’s Brezhnev years (the so-called reunification notwithstanding). The catalog is in German only. But many of Staecks’s posters would require extensive added commentary and explanations to make sense to non-Germans, much like most of Heartfield’s work as well.

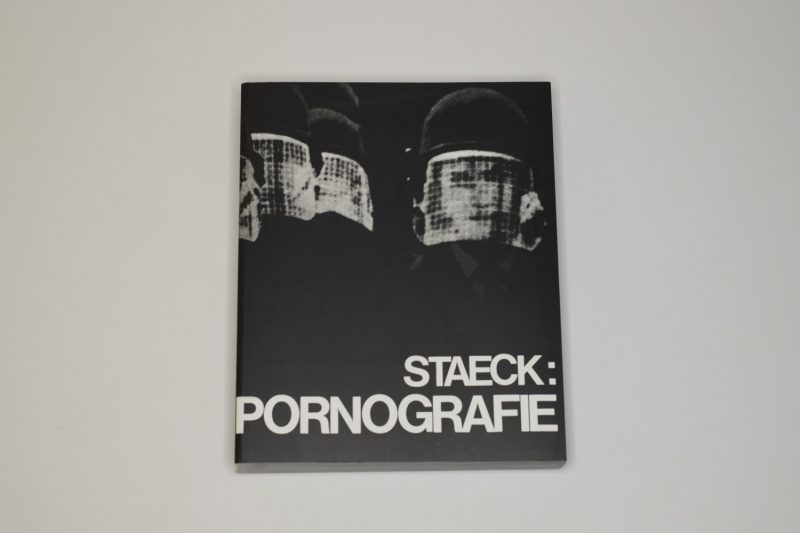

In contrast, Staeck’s Pornografie doesn’t need any added commentary at all. Having read Parr/Badger, I was aware of it. But I didn’t know that in 2007 the original 1971 book had been re-released as a facsimile by Steidl. In many ways, Pornografie is Staeck’s Kriegsfibel, except there’s no added text. Whatever (little) text there is was copied from print publications, like all of the imagery itself. If you want to think of Brecht’s book as his idea of an illustrated morality play, Staeck takes that idea a step further. In a series of chapters, he presents the effects of toxic masculinity, a seemingly endless onslaught of images of violence, whether implied, directly shown, or “merely” its documented aftermath.

These days, the same toxic masculinity is under the microscope again, with one of its main proponents currently occupying the White House. At the time of this writing, no new war has been started. But the display of misogyny, racism, and deluded incompetence has already contributed much to a coarsening of the public discourse that doesn’t bode well for the next decade or two, not to mention the barely disguised presence of fascists and Nazis in both government and the right-wing media (the same is true for other countries as well, of course).

Given it’s so far removed in terms of the times it was made, Pornografie might serve as a useful jolt to all those who haven’t seen it, yet. In a nutshell, the details have changed (the dictators and government thugs, the wars), the details have remained. Plus ça change indeed. As I noted, Staeck organized the material he assembled from print publications into a series of chapters that each are a little longer than is comfortable. When as a viewer you think you got it, you won’t be released. You’ll have to make it through more and more of the same, before there’s another chapter.

The penultimate chapter (7) drives the book’s point home (chapter 8, the conclusion of sorts, comprises just one spread): here, Staeck reproduced advertizing pages from magazines. No manipulation needed, as guns alternate with tanks or anti-aircraft rifles, shaving utensils, insurance, plus the occasional utterly sexist ad that uses women as little more than props in a man’s world. It’s sickening, and it works.

Discussed in this article:

Kriegsfibel; text and appropriated images by Bertolt Brecht; 70 pages; Eulenspiegel Verlag; 1955

War Primer; text (English translation) and appropriated images by Bertolt Brecht; 112 pages; Verso; 2017

War Primer 2 [paperback]; appropriated book with added appropriated images by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin; 200 pages; MACK; 2018

Sand fürs Getriebe; images by Klaus Staeck; texts by Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck, René Grohnert, Monte Packham, Klaus Staeck, Tobias Burg, Gerhard Steidl; 256 pages; Steidl; 2018

Pornografie [facsimile reissue]; appropriated images by Klaus Staeck; 392 pages; Steidl; 2007