Up until now, Chinese artist Cai Dongdong has been known for working with found photographs. The work he has done with his massive archive of photography taken in China over many decades divides into two separate parts.

First, there is what for a lack of a better word is the sculptural work. It involves using specific photographs and creating three-dimensional installations around them. Modifying the source photographs in question might be included. Parts of photographs might be repeated or mirrored or changed in any way necessary to create a segue to the installation around it. Even as there are books that feature this work, it’s best enjoyed in a physical setting. Often, it is subversively funny.

The second strand revolves around creating new narratives out of previously completely disconnected photographs (here’s an example). In contrast to the sculptural work (which in the world of photography is almost sui generis), this narrative-based work follows a relatively well-trodden path. What sets it apart, though, is its incessant focus on China itself, in particular its history (here is another example).

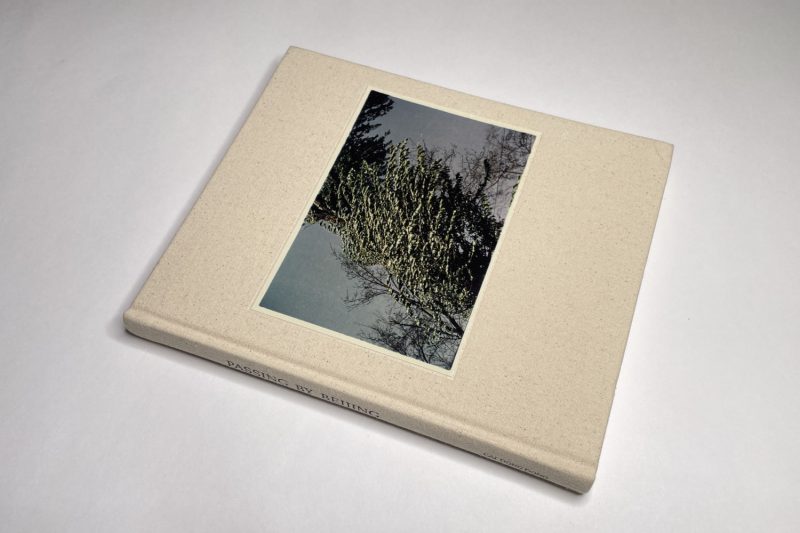

And now there is a new, a third strand, in the form of Passing by Beijing (looking online, I found one bookshop that carries it; if you’re interested, you possibly could also email the artist’s studio to get a copy). “The pictures in the book,” Cai writes in the afterword, “are a selection of color photos I took between 2002 and 2022. They bear witness to my move from northwest China to Beijing […] I have been living in Beijing for for than 20 years, but it has always been a strange city to me.”

That I would have never guessed the environment the photographs were taken in is a meaningless observation: I don’t know much about Beijing. There are a few very obvious references to that city in the book, but they feel more as if a visitor had taken them. Obviously, there might be other references that I simply can’t notice given my unfamiliarity with the city.

Unfortunately, after a brief and feverish run on Chinese photography at the beginning of this century, interest in it appears to have completely disappeared in the West (albeit, from what I can tell, not in Japan). How the photographs would be seen in the context they were taken in or how they would compare with other work made there I have no way of knowing.

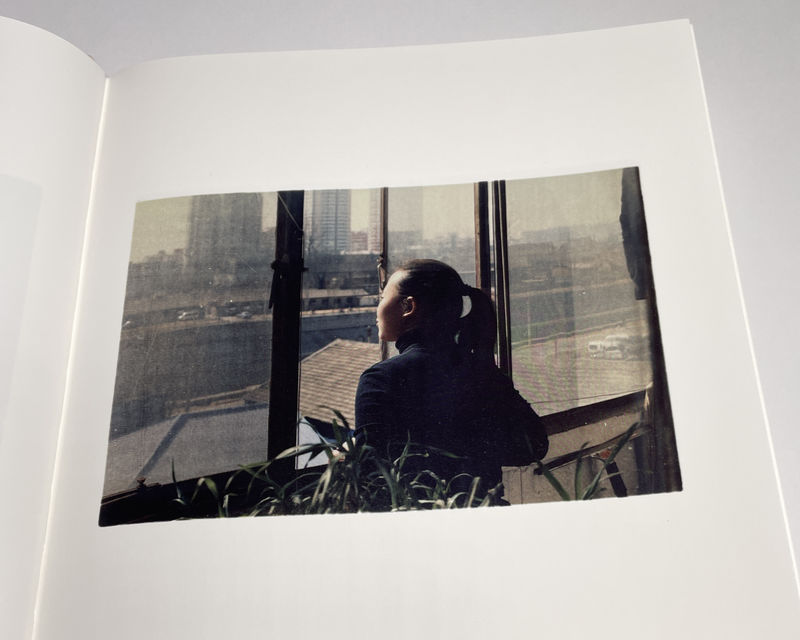

What I do know, though, is how smitten I have been with these photographs: immediately and deeply smitten. To begin with, the pictures very strongly betray their maker’s love for the medium itself. They do not appear to have been made with anything other than a dedication to the camera itself — and all the various things that can derive from that, in particular the very momentary deep engagement with something or someone in front of the camera’s lens.

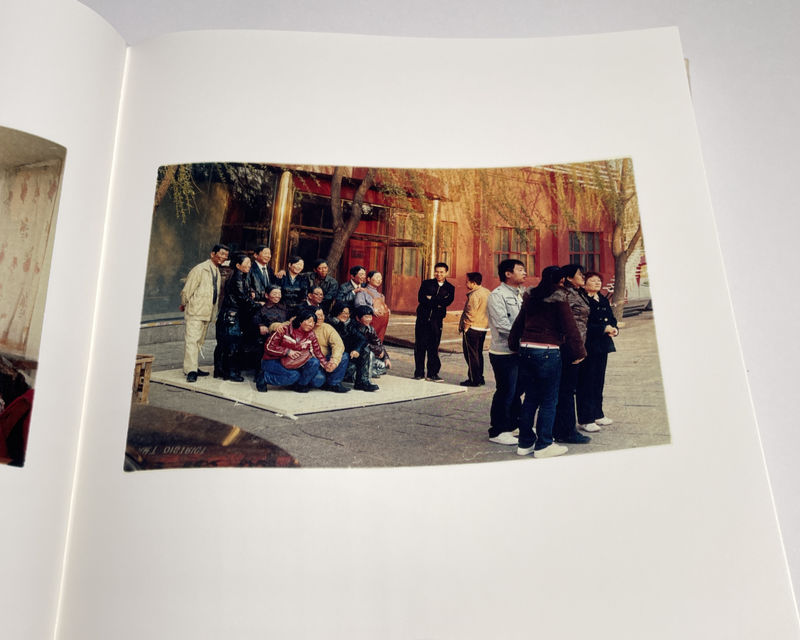

Consequently, the photographs in Passing by Beijing are very heterogeneous. They include landscapes and cityscapes, candid and posed portraits, spontaneously observed still lives, and much more. Ordinarily, it’s a challenge to pull together a coherent and meaningful edit from such a heterogeneous set of photographs (just look at the hot messes in the various re-editions of William Eggleston’s earlier work).

But here, everything falls into its own place. Given Cai’s observant and witty work with other people’s pictures, maybe it should not surprise us to encounter the skill with which he worked with his own photographs. Still, if you have ever attempted to do both — editing other people’s pictures and your own — you know how difficult it is to be a good editor of your own work.

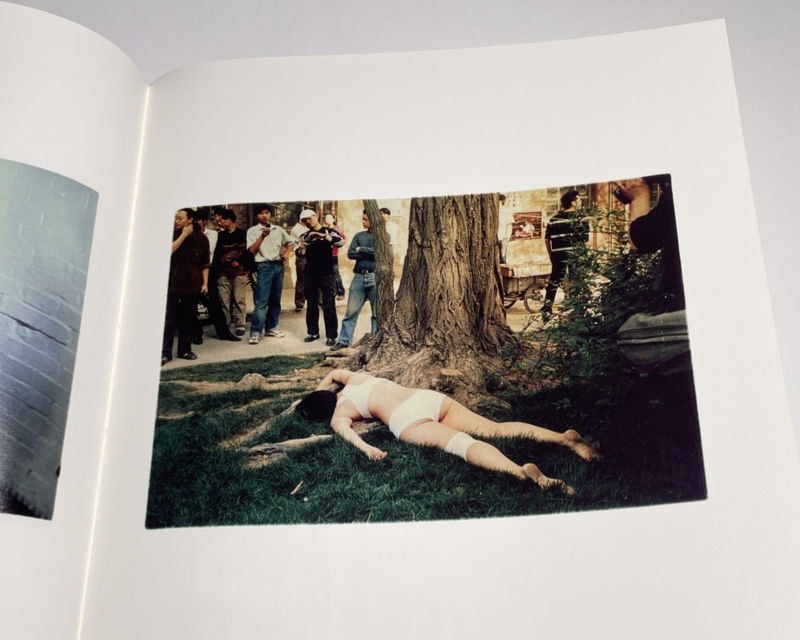

I don’t know to what extent the artist would agree with the following sentiment. There is a pervasive feeling of melancholia throughout the book, a feeling that the moment a picture was taken someone might come and irrevocably alter what has just been captured on the film in the camera. The many people portrayed in the book feel a little bit lost — if not in the world then at least in their own thoughts.

On top of all of that sits the often absurd spectacle that unfolds when many people gather in the same spot, to live their lives beside one another, knowing that any moment is sure to end, and that they all might disperse again. The coming and going is reflected in the built and un-built environment, the latter in the form of wastelands of previous structures the rubble of which is waiting to be removed to make space for what soon enough will be the rubble of tomorrow.

The photographer remains the listless wanderer who at times can’t quite believe the scene he stumbled upon (what’s with the young woman lying draped across a tree’s roots as if she were dead?). And when there is nothing to be photographed, there always is his own shadow.

Given how deeply affecting the photography in Passing by Beijing is, its presence demonstrates that Cai Dongdong is an artist who deserves much wider exposure. Besides the wittiness of his sculptural work and the cleverness and visual literacy of his work centered on history, the artist also is an incredibly talented photographer in his own right.

To be able to do such diverse work on such a high level is an achievement. Let’s hope that Passing by Beijing will find its way into the homes and hearts of people who are passionate about photography and who are done with seeing tiresome reissues of the same old Western or Japanese suspects.

The superficial Western fad around Chinese photography might have become a thing of the past; now it’s time to get serious about truly discovering what artists in China have to offer.

Highly recommended.

Passing by Beijing; photographs and text by Cai Dongdong; 172 pages; self-published; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!