In the Western tradition, human beings first placed themselves outside of the realm of the natural world, equating themselves with lesser versions of the gods they believed in, to then proceed to study what they were surrounded with. If everything had remained at the level of studying, things would not have evolved the way they did: the studying went alongside a process of exploitation and extraction.

In fact, these processes were (and still are) so intertwined that it is not clear why they could be discussed separately. Much like technological progress has been tied to military research, exploitation and exploration are two sides of the same coin. In equal measure, the separation between what we could call hard and soft sciences does not hold either. It was the latter, filled with philosophers, “humanists”, and ideologues, that provided the justification for the exploits of the former. The idea of the enlightenment only sounds good if you keep it strictly separate from its actual consequences. Enlightened Westerners colonized vast parts of the world.

We might note that photography has played a huge part in all of this. Once it became available, it was used in service of all of the above. Seemingly only a tool to gather information, it is exactly that gathering that made the exploitation and extraction possible. Almost by construction, photography’s uncanny ability to turn everything and everyone into a visual specimen resulted in vast parts of the world being treated accordingly.

At the same time, there is something to photography that has it attract those whose main impetus is to collect (or hoard). For example, with all of the above in mind the late Bernd and Hilla Becher’s much lauded typologies — collections of photographs of industrial structures, most of which have since disappeared — could be seen as an expression of the Western mindset now ravishing its own corpse.

On the one hand, you can view the grids of water towers or gas tanks as artistic expressions that celebrate a part of human development that has now disappeared. On the other hand, I find it not hard to be struck by the pointlessness of it all: what exactly do we gain from looking how this water tower looks every so slightly different than that water tower as the consequences of centuries of exploiting the natural world are crashing down on us in the form of — and this is the new term — global boiling?

In much the same fashion, I have always been more repulsed than fascinated by the fact that natural-history museums tend to contain stuffed animals or, even worse, animals suspended in fluids in large collections of jars or other receptacles. As a child already, I found so-called dioramas — little constructed stages that contain stuffed animals in a simulation of their natural habitats — ghoulish. I could never understand why you couldn’t just leave those animals where they belonged — instead of first killing and then preserving them so that they could “inhabit” a museum.

Many years later, I struggled to understand photographers’ fascination with such dioramas. On the one hand, they make for handy pictures — someone essentially stages a picture for you; on the other hand, what exactly do you bring to the scene as a photographer? Showing the constructedness and artifice is good, but it’s also very reductive. I don’t think anyone would look at such pictures and suddenly reach a form of satori about natural-history museums (“Oh now I get it! It’s all fake! That never occurred to me!”).

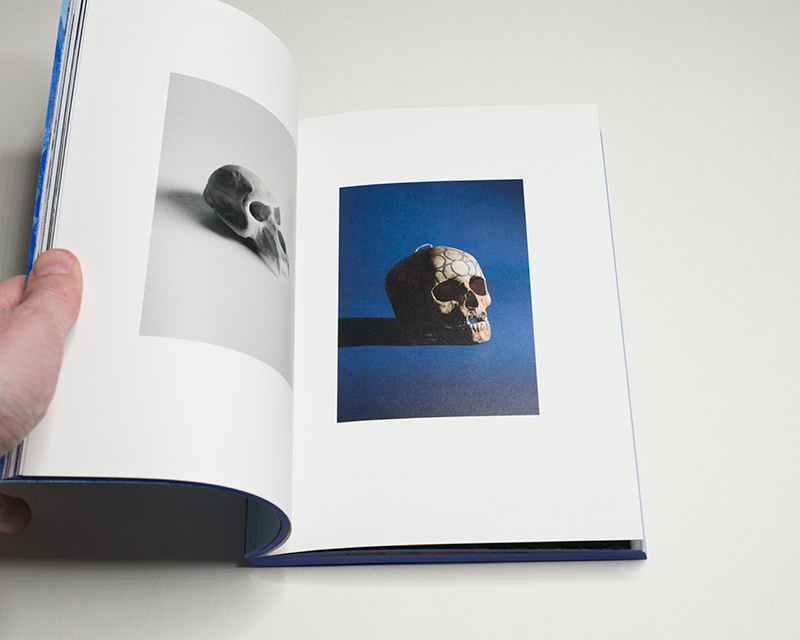

Of all the books I have seen that focus on the above, João Paulo Serafim‘s A Certain Idea of a Natural History goes furthest in terms of trying to bring the various threads together. While it contains a number of photographs from natural-history museums, there are just enough hints of some of the darker aspects of the Western tradition of trying to understand in tandem with exploiting the world (I should add that these come across in the book but not so much in the web page). But I’m also thinking that the work probably could have gone even further in that quest.

In addition, I can’t help but feel that contemporary photography’s currently dominant instinct to produce a certain type of clever stylishness almost by construction keeps things at arm’s length (maybe the most extreme example of what I’m talking about is the work coming out of ECAL). Of course, acquiring such skills is good for photographers who want to move on to produce advertising photography.

But now such advertising photography seeps more and more into photographic institutions. Many young curators love it because it allows them to show work that is critical of certain broadly defined themes without offending the wealthy patrons and corporations that fund the institutions they work at.

Seen this way, this type of photography wouldn’t be neoliberal realism. Instead of propagating neoliberal capitalism, it merely engages in faint token criticism that demonstrates how, you see, libertarians are open to facing the issues (albeit in the most homeopathic fashion). (There probably is a good book to be written about this. If you’re interested in that, you know where/how you can find me.)

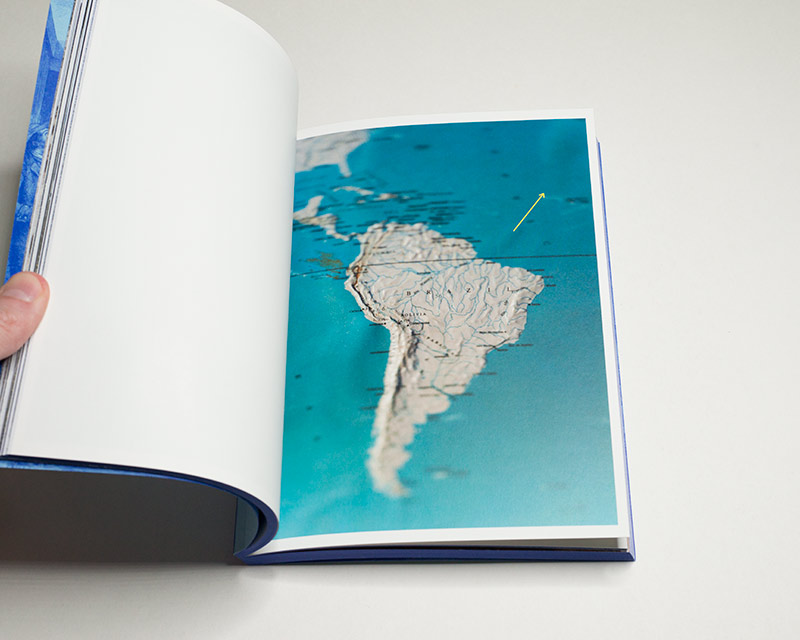

Coming back to A Certain Idea of a Natural History, the book might provide a good jump-off point for an artist (or maybe Serafim himself) to bring out the gruesome consequences of Western exploration/exploitation more. There is a picture of Brazil (a former Portuguese colony) with an arrow pointing towards Europe. There also is a stylish studio still life of the ornament that you can find at the front of Jaguar cars. But that picture is then immediately diluted by its placement next to another studio still life.

As an object, A Certain Idea of a Natural History is a very well made production by Hélice Press, a Portuguese publisher I had not heard of until the book arrived in the mail. In particular, I enjoy the attention to detail as far as layout and design are concerned. This works very well. Furthermore, I found the book listed for 25 Euros at an online book shop. I certainly appreciate the combination of a well made photobook that also is very much affordable.

A Certain Idea of a Natural History; photography by João Paulo Serafim; essay by António Guerreiro; 64 pages; Hélice Press, 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!