What if there’s no hope? What if there do not appear to be any solutions? And what if it doesn’t even look as if anyone cared? Those are bleak thoughts, aren’t they? But they’re not uncommon. I have the feeling they occupy more people’s lives than we’d like to admit. The truth is that there are many among us who are being left out, whose rights to live meaningful lives are being denied, for whatever reasons, whether they’re political and/or economical.

There’s a long tradition in photography to train cameras on some of those people. Curiously, cameras are much more rarely trained on those responsible for the mess, maybe because it would mean directly implicating someone. But that aside, this long tradition in photography has done, well, relatively little to improve the lives of those left out — which is only enough reason to keep doing it.

But there also is a long tradition in photography to provide something uplifting, given that the audience for depressing stories really isn’t that big. We’d like to think, after all, that there is indeed hope, that there are solutions, that things will get better. Those who are left to live in places without hope are then cast out, to be forgotten, but, crucially, to be content enough with what little they have that they won’t raise their heads to, say, suddenly march down the streets wearing brown shirts.

They did march in Hoyerswerda, Germany, in 1991, creating their ausländerfrei zone. The incident shocked the country to the core, which shouldn’t surprise anyone, given its Nazi past. How was this possible? If I remember it correctly many people were very concerned about the country’s reputation, a lot more certainly than about the well being of those refugees who now essentially became refugees in their host country: What might the neighbours think?

Fast forward twenty years, and Hoyerswerda now again is supposed to be a host city for refugees. Meanwhile, the far-right mob now assembles to demonstrate against Islam (you can’t make this stuff up: its founder and leader had to step down after photos of him posing as Adolf Hitler surfaced). Now, all the hand wringing about these kinds of things aside, what mostly gets ignored is the basis for so much of this, a toxic mix of resentment and powerlessness. That mix doesn’t come out thin air.

Instead, it comes out of the air in places where, to get back to the very beginning of this article, it feels as if there’s no hope, where there are no prospects. Pointing out this connection does not and cannot stand as a justification for anything really. But you cannot deprive people of their hope and then expect them to just be happy about that. The resulting resentment that gets amplified in part because there are no debates about obvious problems such as no jobs — that resentment is going to look for an outlet, however ugly.

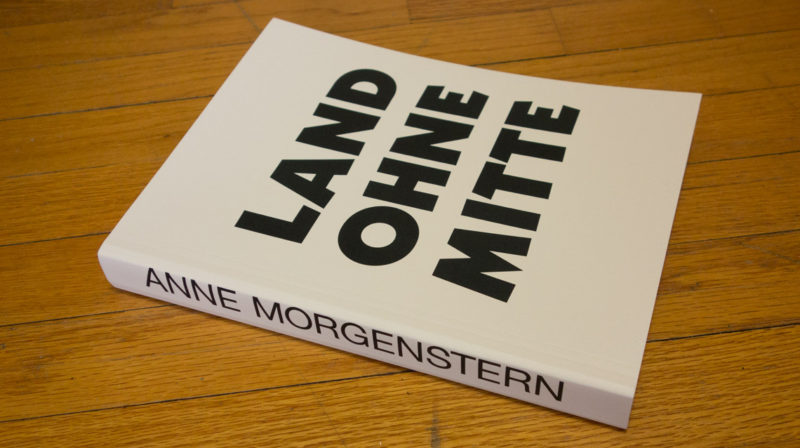

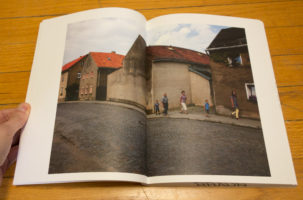

Anne Morgenstern‘s hugely ambitious and challenging Land ohne Mitte (Land without a center) looks at the land around Hoyerswerda and at its people (the photographer’s website features a large number of images from the project). In a sense, the work is quite specific, given its geographic focus, which ties to a very specific history (Germans, no doubt, will approach the work in a fairly pre-determined way).

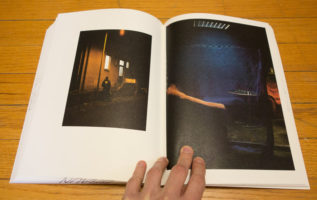

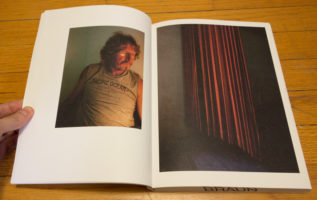

In another sense, given that any of the historical facts are at best alluded to, the photographs actually speak less of the land and its quite specific circumstances, and more of an overwhelming sense of dread, coupled with a lack of hope and prospects. That way, Morgenstern has managed to create a body of work that is a lot more universal than the geographic focus suggests. At the risk of being a bit vague with the use of this particular term here, but the story is very universal, and it can be found in many places across the planet, places literally and figuratively abandoned, places left to fester in hopelessness, which, often enough, is a fertile breeding ground for that toxic mix of resentment and powerlessness.

If the land Morgenstern describes with pictures lacks a center, so does the book. There has been a lot of talk of narrative in photobooks lately, and Land ohne Mitte demonstrates how you can tell a story by not doing it. A lot of books attempting to deal with story telling approach the topic in overly prescriptive (and simplistic) ways. This particular book, however, realizes that there is no simple story to be told, or maybe rather that whatever you might think of as the story really is just what you create in your head when exposed to all those little facets of life.

Despite the obvious differences in the visual languages, Land ohne Mitte references the best of the late Michael Schmidt, through its assembly of moments and characters that appear specific and generic at the same time. Those familiar with the work of Tobias Zielony will also find echos of that artist’s work. Here then lies another very important strand of German photography, less concerned with the single photograph’s pomposity than with layering, with rendering the single photograph almost meaningless. And this new book is destined to find itself amongst the very best books to come out of a country that faces a lot of the same problems now widely shared by large parts of the developing world.

Land ohne Mitte for sure is going to be very high up in my list of the best photobooks produced this year.

Land ohne Mitte; photographs by Anne Morgenstern; essay by Christian Ritter, poems by Margrit Sengebusch (both German language only); 220 pages; Fountain Books; 2015

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 5, Edit 4, Production 3 – Overall 4

Ratings explained here.