To begin with, I can’t talk about Michael Schmidt without acknowledging how much of an inspiration some of his work has been for my own photography. I’m thinking here in particular of his masterpiece Ein-Heit and to a lesser extent 89/90.

***

Whatever you might think about Schmidt’s work, whether, in other words, you like it or not, I think it’s impossible to deny his ability to shape it both through the form of the photobook and the form of the exhibition. In fact, while many artists can be thought of as preferring one over the other, often for somewhat superficial reasons, Schmidt excelled in executing both equally well.

***

The books are what we’re left with. But there also is the major retrospective that is currently on view at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof (it’s due to travel to a number of other venues afterwards), which, alas, I am unable to visit and see. The retrospective comes with a massive companion catalog that provides the basis for these thoughts.

***

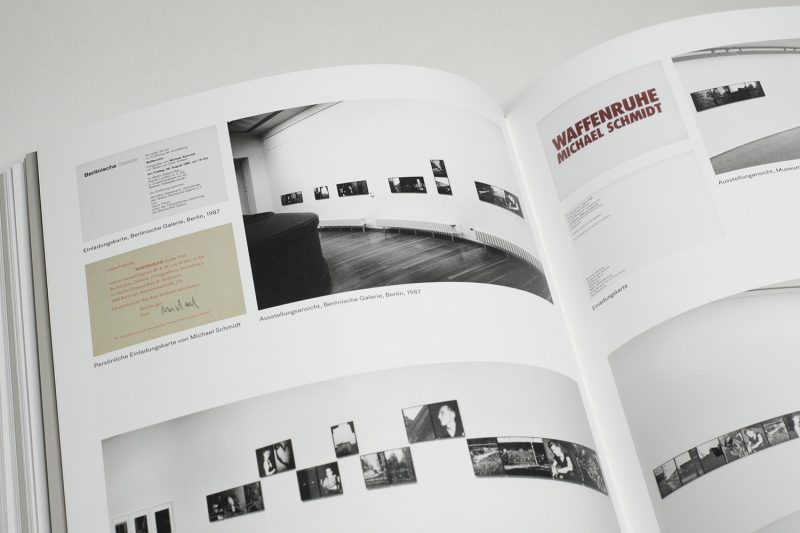

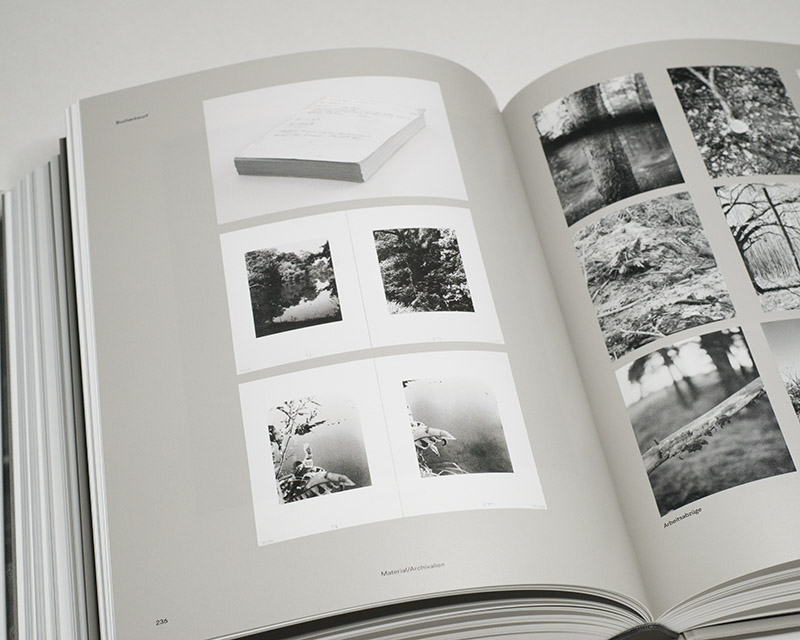

The presence of Thomas Weski as the person in charge of Schmidt’s archive is most fortuitous, given his deep insight into and knowledge of the late artist’s process and thinking. It is Weski who curated and organised the retrospective and who made available a variety of previously unseen material: work prints and other previously unpublished materials, book dummies, exhibition posters and cards, and more.

***

***

I only met Schmidt once, roughly a decade ago at his gallery in Berlin. At the time, I didn’t know all that much about him, which in retrospect might not have been such a bad thing. For sure, I would have been able to ask more specific questions, had I known more about, say, Ein-Heit. On the other hand, when I walked with him to a restaurant in the company of a group who only spoke English and I felt I had to engage in some small talk (which is not something I’m very good at), asking the kinds of questions you don’t ask when you know more about an artist turned out to be a gift. For all I heard about him later — he was said to be famously gruff with people (to the point of grudges still making the rounds in today’s Berlin), he was warm, honest, and open when he spoke of his beginnings as a photographer.

***

When you heard Schmidt speak, you heard a real Berliner: theirs is the German dialect and attitude most likely to offend all other Germans (if you want to learn more about it, this video is very good). If as a foreigner you think Germans are rude, given they tell you what they think (in Germany, to do the opposite would be rude), in Berlin you’re really going to get it. Berliners sound as if you’ve just offended them (which, granted, you might have, maybe by being a bit too coy or precious). I personally find this rather endearing; your mileage might vary. While Schmidt’s general filter might have been a bit on the weaker side, delivering “the goods” with a Berlin dialect for sure helped cement his reputation.

***

Schmidt also was a self-made artist in the truest sense. Born into a rather modest family background and self-trained as a photographer, he never managed to stop people mentioning that his first job had been being a policeman. Add to that the fact that he was not very tall, and you had all the ingredients for what you could think of a bulldog: someone who felt the need to be incredibly assertive while dotting all the i’s. In the catalog, you see a larger number of materials that hint at Schmidt’s attempts to present himself in a very specific way.

***

***

Given that Schmidt had to learn how to be a photographer without much of a formal education, the form of his books and exhibitions for sure comes as no surprise. He worked incredibly hard on them because he felt he had to. There was no other option. There was no room for sloppiness. Sloppiness would have had people talk about the former policeman who now wanted to be an artist (Germans can be ruthless when they want to). And what he demanded from himself, he demanded from others (which in general isn’t a good idea).

***

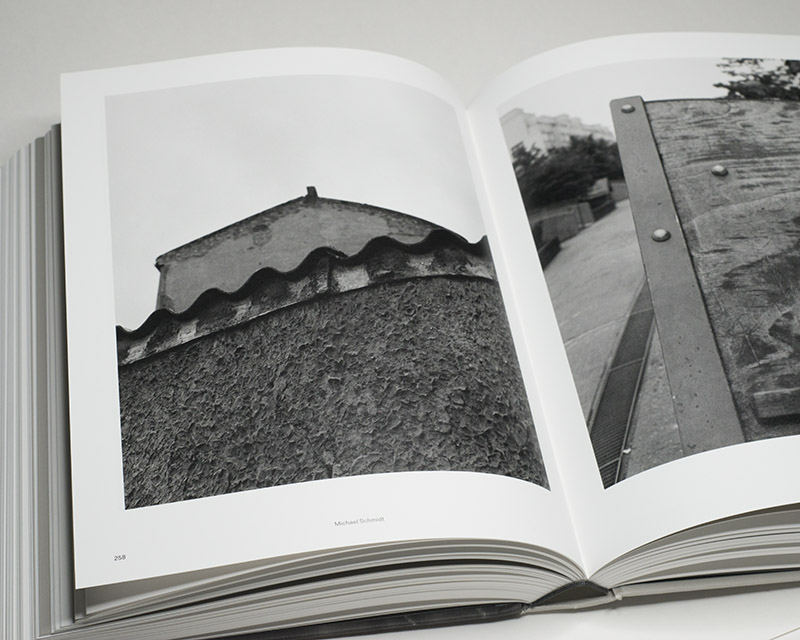

In the book, there is a letter he wrote in which he detailed his method of photographing. “In order to learn more about a district, I drive down each street twice in both directions using the district map; this means that I have seen every street and its buildings in the district usually at least twice, but often even more often. […] Per day, the task is to cover and view roughly 1/20th of the district. On my map, I mark each path that I took or drove.” (p. 32 in the catalogue’s German edition; my translation) In light of this, a body of work such as Berlin nach 1945 with its variants of views of the same street becomes instantly clear: Schmidt was looking very, very hard for pictures.

***

This is a very interesting approach to inspiration: you don’t wait for it to come and then start work. You work and work, and things will take off when it arrives — in part because it will be triggered by something you encounter while working. But it might not arrive for many months.

***

***

Schmidt also looked very hard at pictures, his own as much as other people’s. The catalog unfolds a breadth of work that makes it clear how much he must have looked, how much he must have taken in from others. I found myself surprised at this breadth. I also noticed how certain motifs kept recurring (not necessarily in the same form, though).

***

There is, after all, the Schmidt beyond the Waffenruhe one, beyond the Ein-Heit one. One was steeped in a New Topographics approach (as in Berlin-Wedding and Berlin nach 1945). There was the early Schmidt who was clearly inspired by classical social-documentary approaches, which today are mostly dismissed for the wrong reasons (it is as if some people can only imagine a Waffenruhe Schmidt). There’s the late Schmidt who’d occasionally misfire (as with the dreadful Frauen), and who’d then move on to bring back colour and considerable experimentation with Lebensmittel. And yes, colour had been a part of Schmidt’s early commercial work, as is being shown in the catalogue.

***

I find it interesting how consistently Schmidt managed to arrive at high quality. Of all the books I’ve seen I can’t think of one where there are too many or bad pictures.

***

I don’t necessarily want to speculate about the man’s personal life. But I’m thinking that it can’t have been easy being Schmidt. I remember Thomas Weski showing binders filled with contact sheets at the archive. Going through an in-between year provided a glimpse at the stark reality of relentless art making or rather: of failing to make art. Schmidt strove to at least partly re-invent himself after a finished body of work, and that was evidenced by his contact sheets. The process must have been a painful, with talk of a former policeman pretending to be an artist just one misstep in the final result away.

***

***

At the end of the day, there will have to be a re-writing of the history of German photography. That new history will have to accommodate the fact that for a while there were two strands of German photography, an East German one and a West German one. Their joint tradition notwithstanding, there were clear differences. Schmidt clearly was a West German photographer. Berlin is said to have been his subject, but no, it was West Berlin.

***

The difference between East and West German photography does not come down to good or bad. Instead, it’s a matter of recognition. For the most part, the history of the medium has a lot of work to do to give East German artists their due: A future history of German photography must not follow the lead of “re-unification,” which in reality and form was an incorporation of East Germany into the West German federal structure with very little, if any adjustments by the West (the consequences of this fact will be with Germany for a long time).

***

Back to Schmidt: here we have a West German photographer operating in West Berlin, making West German work. There’s nothing wrong with any of that, but we also need to be very clear about it.

***

Having seen the archive and the previously unpublished material in the catalogue has left me wondering to what extent there is something else in Schmidt’s oeuvre that could be unearthed by a curator. Of course, this is where things can get iffy: after all, to what extent can you, should you look into something an artist decided against publishing during their life time? For sure, Schmidt’s case is bit different than Winogrand’s (where there were all those undeveloped rolls of film — if an artist doesn’t even look at their work, why should anyone else?). In fact, you could already extract a few unrelated photographs from the catalogue and create something different.

***

With some of Schmidt’s books re-issued (Weski has been doing a stellar job bringing the photographer’s work back), the one still missing is Ein-Heit. As I wrote above, I consider it as the by far best body of work. Its ambition and scope is unsurpassed. It’s dense and opaque. It doesn’t necessarily make for the most rewarding experience unless a viewer is prepared to immerse her or himself repeatedly. Given its many historical references, a reissue might want to include a study section that reveals some of the historical references (the catalogue shows the sources of two images appropriated by Schmidt).

***

The catalogue contains a number of in-depth essays by authors who worked with and knew Schmidt and who are able to provide more context around the different stages of the artist’s career. It’s a most attractive and hefty package. If you have almost 5cm/2″ to spare on one of your bookshelves, do yourself a favour and get a copy.

***

Michael Schmidt: Fotografien 1965–2014 (or Photographs 1965–2014 in the case of the English language version); essays by Ute Esklidsen, Janos Frecot, Peter Galassi, Heinz Liesbrock, Thomas Weski; 400 pages; Koenig Books, London; 2020

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.