It was a family connection that brought Kevin Mertens to Iowa. He wanted to photograph his father’s town of birth, and he had lived there for a while as a child. Mertens didn’t find what he was looking for: “I asked myself how it could be that in past visits I hadn’t noticed all the worn-down houses, the empty stores, the exhausted looking people.”

I’ve long been undecided about who is better suited to portray a place, any place. Is it someone born and living there, intimately familiar with things? That intimacy might come at a high cost, with, possibly, too many attachments creating too many filters. How can one truly see something one is familiar with? The outsider does not come with that baggage. S/he can explore, but the task of getting under the surface is much harder, and that surface might be too tempting with its many distractions.

I don’t think there is a real solution to this conundrum. I don’t think the insider’s view is preferable over the outsider’s, or the other way around. No place carries with it a true, real story. There are stories we attach to places, some better than others. But to believe that somehow we can unearth or produce the real story, the truth about any place is a folly. There is no such truth. Photography, with its seeming ability to depict the facts, the truth, still has to come to terms with this.

The worn-down houses, empty stores, and exhausted looking people Mertens encountered in Iowa then led Mertens to a man named Jerod first, and to many other people later. The result, Hurtland, is the story of young people trying to make do with what is around, with the world they’re going to inherit soon enough, a world where there aren’t the opportunities any longer enjoyed by their parents or grandparents.

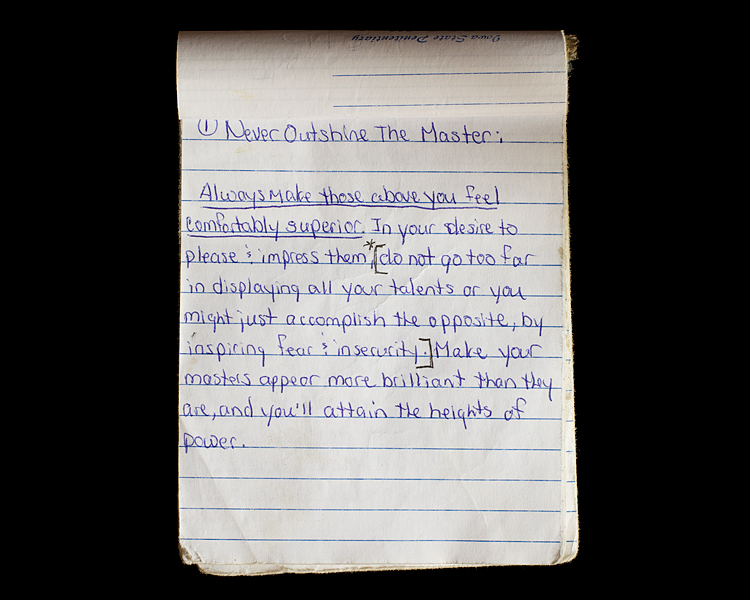

How do you deal with the world you find yourself in? There is no recipe, even though having some ideas, possibly some rules, might help. You’ve just got to be able to grasp something so you can attain some certainty. There has got to be a compass of sorts. In Hurtland some of the rules are provided in the form of The Laws of Power. Passed down from someone’s father (who had written them down while being in jail), they are actually copied from a business bestseller.

There lies rich (and sad) irony in the provenance of these “laws.” The Machiavellian world of business has made large parts of American wealth, and it has also been responsible for the decay many towns are now suffering from. It is questionable whether the young people in Hurtland would embrace these laws had they not been copying down in prison, thus giving them a sort of totemistic power, or maybe more accurately changing their original totemistic power (if you go to the so-called Business section of your bookstore, there is no shortage of books creating whole worlds of often completely absurd make-believe) into a different one.

I sense a pervasive sadness in Hurtland, a sadness not unlike the one picked up so brilliantly by Vanessa Winship in She Dances on Jackson. What will the future hold? We’d all like to know. Somehow, across the land there appears to be the growing realization that whatever the future might hold, it is not going to be what was and still is being promised by those people on TV.