The notion of the male gaze appears to have finally become well known enough in the world of photography. Consequently, there now exists an awareness of the many problems that derive from it, even as often enough, the male gaze is simply being equated with a man being behind the camera and a woman in front of it. Unfortunately, that simple approach runs the risk of reducing what ultimately is a question of power and agency down to almost a technical problem — as if non-male photographers were unable to perpetuate the many problems created by the male gaze.

But the agency of taking a picture is not necessarily the same as the agency to define how in a picture a person, or in this case, a vast part of the population is being defined. If you view the problem from this angle, subverting the male gaze requires a multi-pronged approach, in which non-male photographer being behind cameras plays a crucial, but not exclusive part.

In a nutshell, given the history of the medium new photographs not only have to contribute to establishing a countermodel to the one produced by the male gaze, the one where the world is not only seen with male eyes but in which it also unfolds through laws created in the male mind. There will also have to be photographs that subvert all those existing photographs that still make up a sizeable fraction of photography’s history.

Around the time that John Berger and Laura Mulvey introduced the male gaze, Marianne Wex produced an extensive body of work that in its English version became known as Let’s Take Back Our Space: Female and Male Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. Decades before manspreading became widely discussed, Wex studied exactly that: how body language was not only being performed but also perpetuated to cement gender roles (and thus the inequality between men and women — please note that given the time Wex compiled her work, it focused on traditional gender roles).

I’ve always liked that title, Let’s Take Back Our Space, because it centers not on the photographs themselves but on the intended goal, a subversion of existing norms and a resulting shift in agency and power. Were photography’s history to remain unchallenged, we might get the former but not necessarily the latter — and I suppose it is exactly for that reason that there has been so much resistance from many male photographers to deal with their own medium’s extremely problematic history: power is almost never ceded voluntarily.

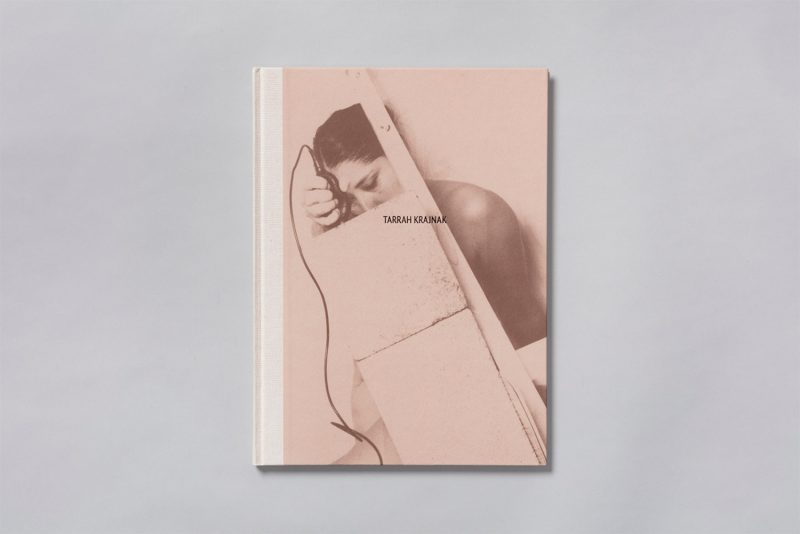

Tarrah Krajnak‘s Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes now presents another addition to this steadily growing canon of feminist photography. Using Edward Weston’s nudes as a starting point, the artist meticulously re-stages them, using her own body instead of a model’s.

Krajnak not only explicitly asserts her own agency as a woman photographer, but she also asserts her agency as the subject of the resulting photographs. This latter aspect is crucial. The resulting photographs reproduce Weston’s original closely. But through the inclusion of the studio set ups and the clear presence of the remote shutter release, her own determination to undercut the “master” becomes very clear.

The inclusion of the original photographs in the studio setup of course helps all those viewers who might not be familiar with the source material. But Weston’s photographs essentially also get to function less like artful photographs well known from the history of photography and more like illustrations from a “how to” book about photography.

This aspect alone undercuts their value while also revealing the mechanism in the background: Weston’s nudes aren’t merely innocent photographs that happen to have become famous. They’re programmatic, establishing a visual hierarchy in which the (young) female body has to perform as material for a(n older) male photographer. Krajnak explicitly rejects this model. Her pictures very powerfully proclaim that if anyone ought to be able to determine the presentation of a woman’s body, it is first and foremost the woman herself — and not some older “master” photographer working with a “muse” (possibly the yuckiest word used in the world of art history; please note that this discussion extends beyond traditional gender roles).

Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes follows the tradition established by Jemima Stehli who re-created Helmut Newton photographs using herself as the model or who invited a number of male critics, curators, and art dealers to sit in a chair while undressing in front of them, giving them the cable release so they could take the picture. If you have never read Adrian Searle’s description of his experience, you might as well now. You can see some of the photographs in this interview.

Not all photographs in Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes are re-creations. There also are a few in which a book entitled Darkroom 2 (that has one of the nudes on the cover) is given the role of a prop. Using the same strategy as in the other photographs, with these pictures Krajnak connects Weston to all of his peers, whether contemporaries or later.

Furthermore, there are photographs without any of the references, another deft choice to reach the goal of — to use Wex’s expression — taking back a space previously expropriated, the space in which the female body is governed solely by those who inhabit it — as opposed to older male strangers.

Recommended.

Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes; photographs by Tarrah Krajnak; 52 pages; TBW Books; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!