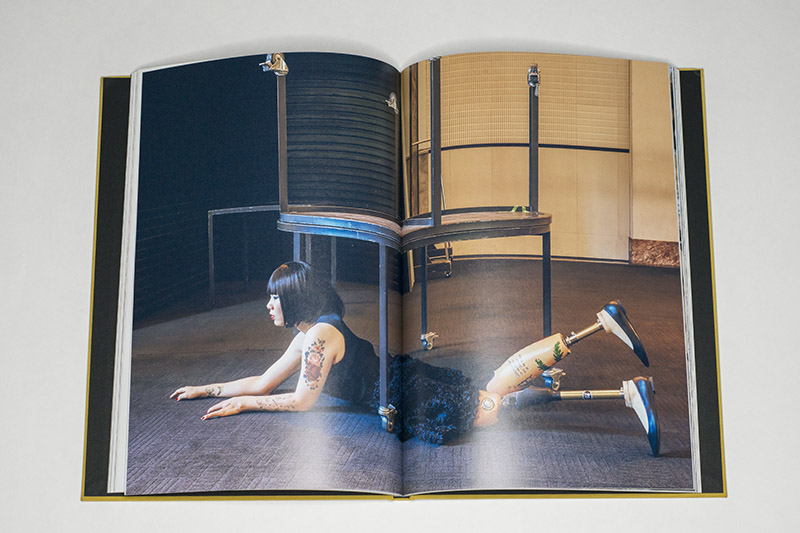

Mari Katayama‘s art cannot be easily separated from her biography, specifically the fact that she was born with tibial hemimelia, which resulted in her decision to have her lower legs amputated at age nine. As much of the work is about the artist’s body, thinking about it as originating from there strikes me as a fruitful approach. After all, in the strictest sense, most of the photographs are not of a documentary nature (even though some are); and the center of the work is not the artist’s body but, rather, what we all share, regardless of what our bodies look like: aspirations and dreams.

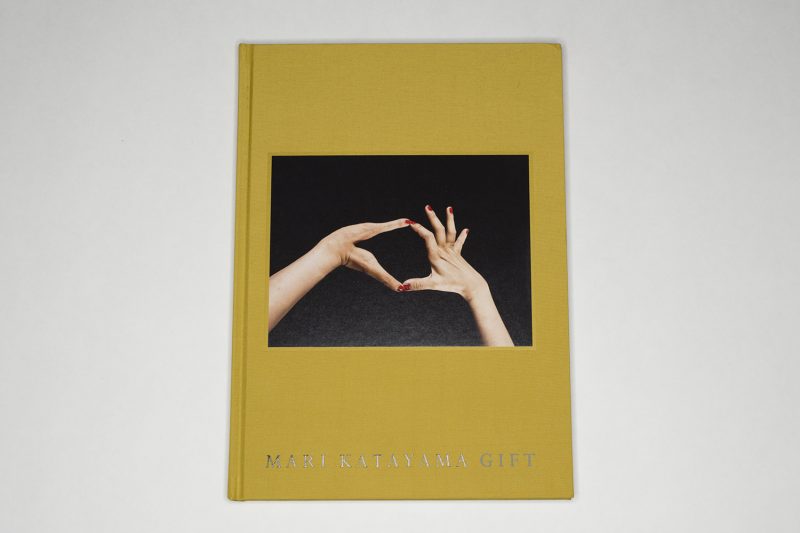

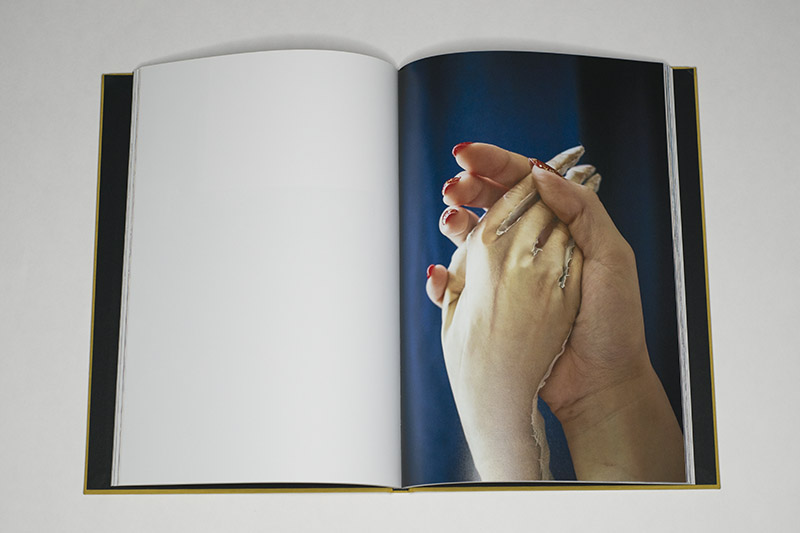

A recent survey entitled Gift now makes this work more widely available, and it allows for a deeper engagement with an artist whose most well known photographs cover only some aspects of her larger concerns. To begin with, Katayama is not just a photographer. She also produces a variety of objects that are either used as props in her own tableaux, as objects to displayed alongside the photographs, or as objects for use in her own daily life.

If most artists’ work can be understood as emanating from the inside of their studios to the outside world, here the beginning is originally the inverse of that approach. For example, the elaborate ornamentation of prostheses was made for daily life, and only later did it become a focal point to be displayed in photographs.

I often yearn for photography to be more than merely pictures on a wall and this provides one of the reasons why this book (and obviously work) is one of the most impressive bodies of work I have seen in a long time. Often enough, however, photographers’ attempts to supplement their picture with something else, be it film or sculpture or whatever else, ends up being clumsy and bit sad. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but most photographers know only about their medium — they are trained in it and only it.

In contrast, photography is a tool for Katayama much like sewing is. This artist produces photographs not to be a photographer but rather to create something that will express an idea just as much as a hand-made sewn artificial body or body part might (which, in turn, might show up in a photograph). What one might think of as props are anything but, and this is what separates the Japanese artist from, let’s say, Cindy Sherman who also places herself into her picture and who does work with props: Sherman embodies someone else, expressing their desires; Katayama embodies herself, expressing her own desires.

Another difference is the scope of the work. In many of the works, the Japanese brings together a variety of threads, including, of course, a preoccupation with the body and its possible limitations, but also ideas of femininity and of societal expectations of how both the body and femininity ought to be presented. Given the artist is female, these expectations obviously overlap very much.

Another aspect that I personally can only vaguely understand is the artist’s place in her home country, Japan, which — as far as I understand it — places very restrictive rules concerning conformity upon its people and especially on women. Japan is not a country known for its high level of gender equality. This fact makes Katayama’s work more political than it might seem.

Gift presents all of these aspects through a survey of Katayama’s work that — thankfully — is not organized chronologically. Instead, after a brief introductory section (that includes an essay by Simon Baker), the first colour images mostly focus on objects — painted prostheses and the various handmade objects that play a role for the artist. I feel that this is a deft and good choice.

After all, in light of the preceding it might be clear that the tableaux photographs — in all likelihood the pictures a viewer might know this artist for — are important, but they need to be seen in their wider context. Those photographs are attention grabbing and good for this day and age of viral imagery. But they are so seductive that they might tempt a viewer to ignore some of the details at the expense of others.

Ultimately, Mari Katayama’s work centers on what it means to be alive, to be a human being in this world where few people can easily be who they want to be, and the rest of us have to work with what we got and assert ourselves. Given both her home land and the biological aspects of her biography, the artist’s task obviously is a lot harder than most other people’s.

I’m tempted to think that the breadth of Katayama’s approach in part derives from the larger media environment available now. After all, social media are filled with people who are shaping their own self through the presentation of images. However vapid many of those attempts on social media might be (the celebrity aspect for sure appears to be the most prominent one), Katayama makes it clear that there is more to the idea than just celebrities or influencers. Seen that way, these photographs are not merely an expression of her self, they also are an assertion of it.

“The world is a big place,” Katayama writes in her essay, “and we can do anything in it, but it is all mapped out, and we are all going to die one day. So here I am, spending another day between endlessness and limitations, against a backdrop that never changes.”

If I had to pick one photobook as my favourite this year, it would be this one — for all the reasons outlined above and all the other ones I still cannot put into words.

Highly recommended.

Gift; photographs by Mari Katayama; essays by Mari Katayama and Simon Baker; 136 pages; United Vagabonds; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.