It’s fair to note that Daidō Moriyama’s photography have found their true expression through print publications. The same can be said for many other Japanese photographers, given that in Japan the gallery system did not play the role it did in the West. For a while Moriyama even maintained his own private gallery, entitled Camp.

Camp existed during the years when Moriyama’s own photography appeared to be on the back burner. After his initial flurry of publications, some of them directly connected with the short-lived and influential Provoke group, starting in the mid 1970s until the late 1980s, there is a curious gap in many biographies of this photographer, which, unfortunately, has resulted in Camp not being as well known as it ought to be.

As a brief aside, given the crass neoliberal turn the commercial world of art photography has taken in the West, the idea of Camp has much to offer for photographers today who can’t find their place at the table where the crumbs dropped by the wealthy are being distributed.

In 1972, Moriyama published the first issue of a magazine he called Kiroku (or Record in English, which I will use from now on). “I would like to create a certain tension or antagonism between myself as portrayed in other media and myself as portrayed here in Record,” he wrote in that issue. There were four more issues, and then Record stopped — until it was revived in 2006, following a suggestion by Akio Nagasawa, an acquaintance of Moriyama’s.

“I was addressing myself rather than other people,” Moriyama wrote in issue number 6 about the past, “I wanted a simple, basic title. Sadly, Kiroku ended with the fifth issue. Production costs had doubled in the wake of the seventies oil crisis. I can’t deny that I was also a bit tired of the project.”

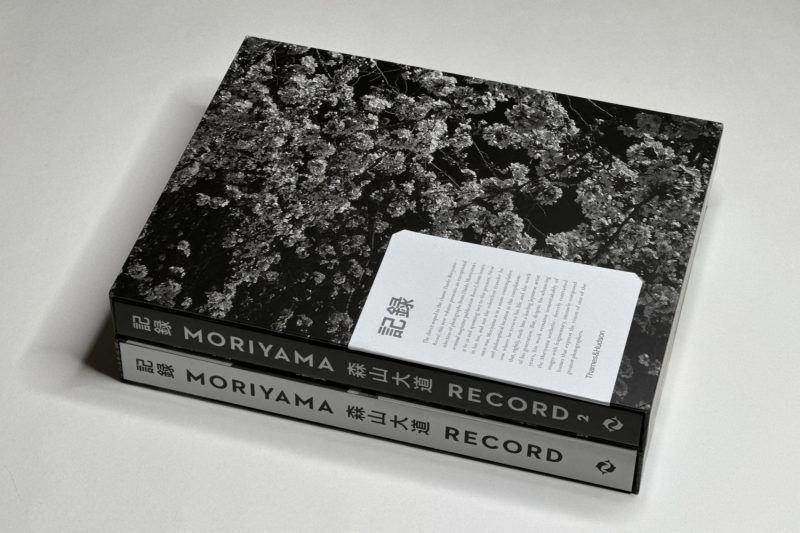

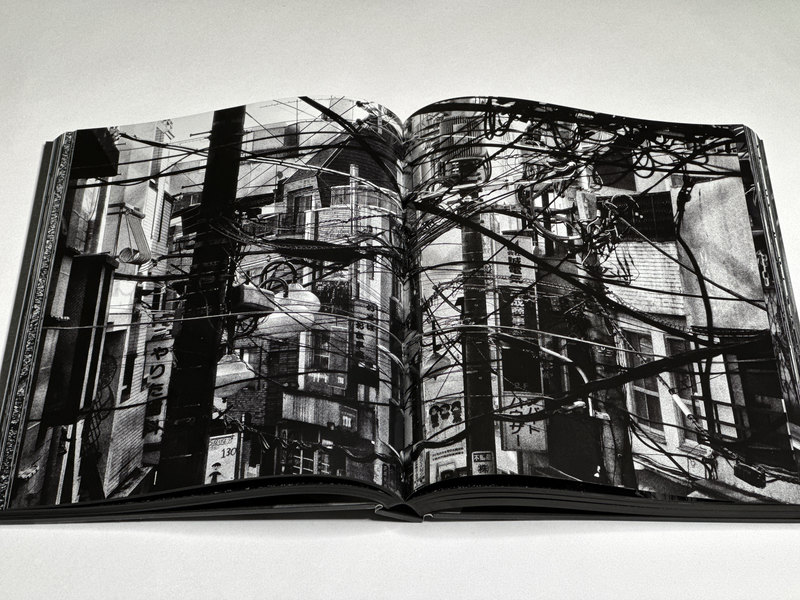

A selection of work from the first 30 issues of Record was published in 2017 (Moriyama’s quotes are taken from the book). A second selection, from issues 31 up to 50, has now been published as Record 2.

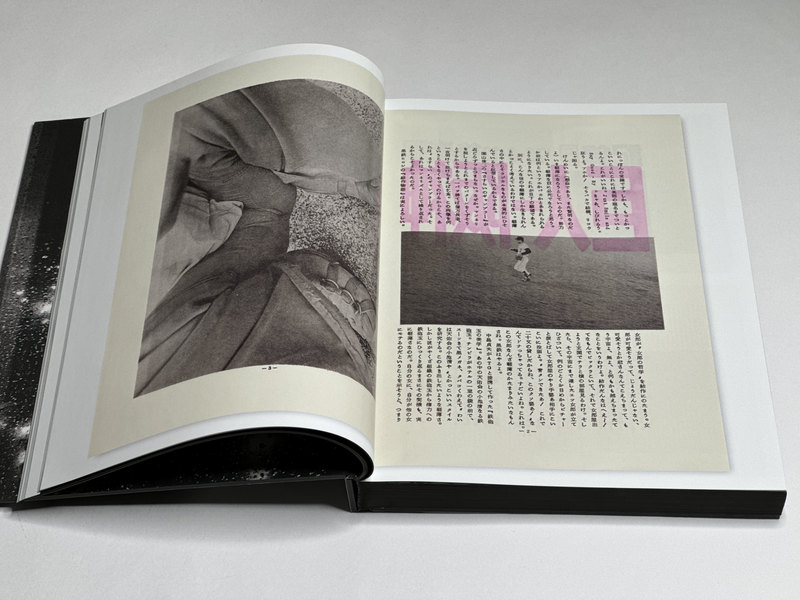

Both books were edited by Mark Holborn. In a nutshell, while Record contains occasional reproductions of spreads from the magazines (an approach well known from the various books about photobooks), in both books you get parts of the magazines reproduced (all in full bleed), alongside translations of the short introductory texts written by Moriyama.

If you wanted to think about the various issues of Record as a zine, I suppose you could. As far as I understand it, the term zine contains an element of setting things apart: whether it’s their makers proclaiming that they’re not part of the crowd or the crowd proclaiming that, well, those are zines (pronounced in a fashion that evokes the mental image of one’s fingers touching something unsavory).

It might seem a little bit strange to consider one of the most well known Japanese photographers as a zine maker. But if you look at Moriyama’s career, there certainly are many occasions of him brushing against the grain, whether as part of Provoke, as driving Camp, or his various approaches to making his own books. Someone who published a book entitled Bye-Bye Photography for sure wasn’t trying to play it safe.

Alternatively, you could view Record as coming closest to a form of diaristic photography. After all, the 20 issues contained in Record 2 cover the six-year time period from April 2016 until March 2022, meaning that there were roughly three issues every year.

These contain a mix of material, with some issues focusing on the by now familiar photo walks (“I crisscross the central Tokyo area, taking pictures almost daily.” — Record 34) or others produced during trips abroad to attend to an exhibition or prize ceremony (“Last November, while Paris Photo was on, I went to Paris for the first time in two years for business connected with the fair.” — Record 40).

But there also are occasions for Moriyama to look back and to reminisce, and it is these in which the emotions manage to break through what clearly has become the routine of essentially taking the same kinds of pictures over and over and over: “In early November I had some business to do in the town of Zushi,” Moriyama writes for Record 36, “I have a house there and usually visit two or three times a year. The more I drive along the coast and through the streets of the town, the more the images of a young Takuma Nakahira flash through my mind. It’s natural considering that fifty years ago we were close friends eagerly discussing photographic dreams while we walked together through the summer mornings, noon and evenings.”

It is too bad that there is the long gap between 1974 and 2006. To imagine the kinds of issues Moriyama might have produced, chronicling his life and events around him… While especially the years around Camp deserve to be unearthed, an endeavour made difficult by the photographer’s personal problems at the time, the issues of Record we have available cover his earliest, artistically most fruitful time period and the time today, with his name forever etched into the pantheon of contemporary photography.

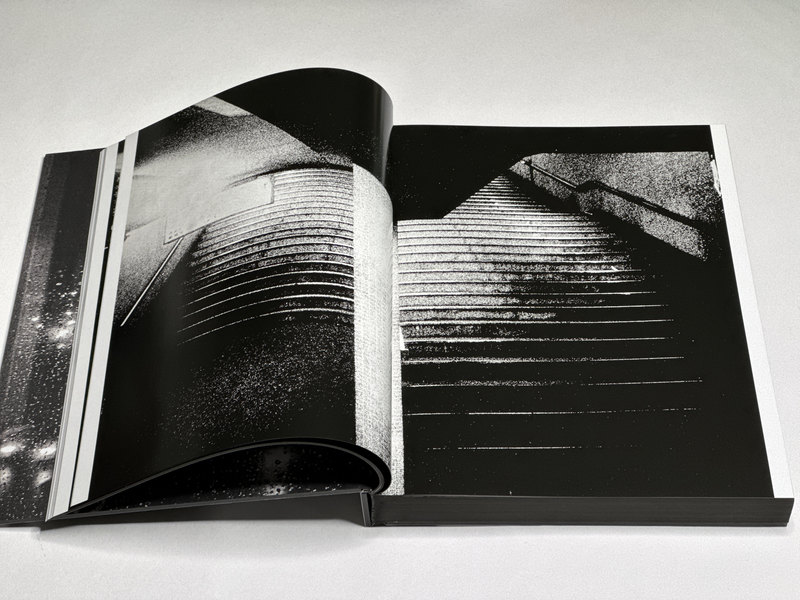

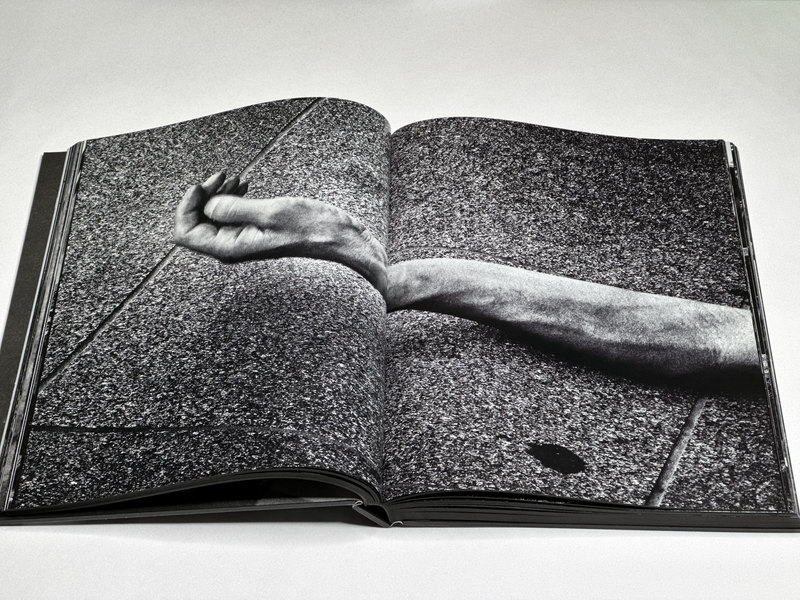

To approach Moriyama’s Records with the idea of looking for great pictures would miss their point. Even as there is something to be said for careful editing of one’s work, not doing that at all has its advantages as well. If one decides to live one’s life with and in photography, one might as well delineate both — the life and the photographs — with a steady stream of publications that give witness to it all.

After all, the chase for the good pictures that can survive a ruthless edit can be crippling — I’ve encountered as much in students when teaching. What if the idea of the photograph as that precious gem can simply be discarded?

In retrospect, in a world where so many people now do what Daidō Moriyama has been doing for decades, namely relentlessly photographing and sharing their daily lives (much to the chagrin of curators and photography critics wedded to outdated, lazy thinking around photography), this Japanese photographer could be seen as being the true avant-garde yet again, first as a member of a new generation of photographers challenging their elders, and then as the prototype photographer for all those who now make good daily use of the cameras in their smartphones.

Even as it seems clear from Record 2 that the sun is slowly setting over a life in photography, Moriyama’s true legacy is going to remain with us for many years to come. But you will have to look past the harsh contrast of the black and white in the photographs to discover the multi-faceted human being behind them.

Record; photographs by Daidō Moriyama; edited from Records 1 through 30 by Mark Holborn; 424 pages; Thames & Hudson; 2017

Record 2; photographs by Daidō Moriyama; edited from Records 31 through 50 by Mark Holborn; 352 pages; Thames & Hudson; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!