“The works on pages 13, 17, 21, 49, 51, 47, 49, 65 and 97 were made by my daughter Laurie,” writes Thomas Manneke in the very brief afterword in the colophon of his book Zillion (yes, 49 appears twice, possibly an oversight). If I have one complaint about the book (and it is just this one), it’s the title. A book like this, a book filled with playful photographs and wonderful portraits, ought to have a better title than Zillion. Unless zillion is also a word from a language other than English, a language I am not familiar with, and in that language its meaning conveys grace, wit, and joy.

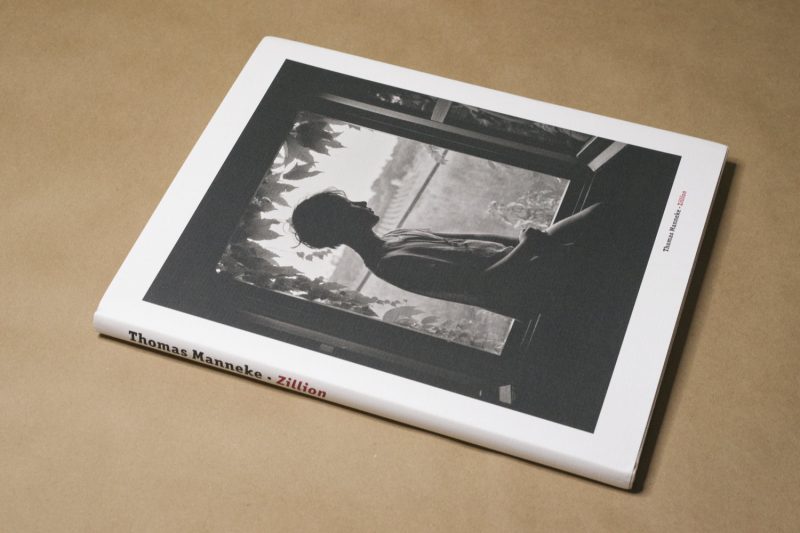

Laurie, the photographer’s collaborator, also finds herself in front of her father’s lens in a series of portraits, some of them taken in domestic settings, some of them outside. Those with good visual memory might pick up on the visual echo in the cover photograph. It evokes a classic Dutch photobook that isn’t as well known outside of the Netherlands as it should be: Johan van der Keuken and Rempo Campert’s Achter Glas.

A fun fact as an aside: when I looked on YouTube if there is a video of the book, using “achter glas keuken”, I ended up with a string of videos intended for home renovations. “Keuken,” I believe, is “kitchen” in Dutch, and “achter” means “behind”. Between the Dutch home-repair videos and the ads I didn’t have the patience to locate a video of Achter Glas (assuming there is one). I’ll make one myself once I found my copy in the many moving boxes.

Regardless, even as the 1957 book contains a very different story, there is a shared photographic sensibility. This is interesting because when Van der Keuken took his pictures, he was a teenager who, I wager, was still mentally embroiled in the transition of the world of children to the world of adults. His portraits of friends and acquaintances are very stylish, but they’re also very tender.

Somehow, Manneke, who clearly is much older (it would seem that his daughter is about to face that threshold that Van der Keuken had just passed) managed to bring the same spirit to the photographs of Laurie. That’s really impressive.

I’m writing these words not merely as a critic but also as a photographer whose portraits always end up on the slightly unsettling side, even when the people in front of the camera are not that much older than Van der Keuken was in 1957. It’s not that I mind this fact — it works well for my work around fascism, but at times I do hope that I were able to make tender portraits.

Regardless (again! so many asides!), one of the portraits of Laurie (page 47) hits the Van der Keuken note most strongly. The young girl is looking at the camera, and with her left hand she is holding a little object (a shell? a piece of wood? a stone?) against her body, just below her neck. I know absolutely nothing about Laurie, but I see someone who knows about the transformative power of the camera. She exudes — or maybe would like to do so — a sense of confidence beyond her years. It’s incredibly charming — and vulnerable in the way that you can only be at that age.

The “works” referenced by Manneke in the quote I began this article with are constructions made with the intent to be photographed. Some of them were inspired by other artists’ works. That said, not all of the objects in the book were made to be photographed. Some were simply found and then subjected to the same treatment such as, for example, some foam packing material that while discarded in the street through Manneke’s camera becomes an object of intrigue.

Art is all around us, the book says, and where there is no art it can be made out of the simplest materials: take anything — some cardboard, some metal coils, some pieces of tape, and with a playful pair of hands a piece of art can be had quickly and easily. This is, of course, the world of children, even as they are not too concerned with art, or rather our adult way of thinking of art, a thinking devoid of playfulness and filled with shallow pretense.

Sometimes, you only find out that you had been waiting for something when it actually arrives. Certainly this was the case with Zillion for me. I had been waiting for this book — or for a book that would do what this one does.

Of late, photography has become such a joyless affair, for reasons that I can only speculate about. I will not do that in public, because people tend to get upset, and I don’t need that any longer in my life. Everything about it has become joyless: the making, the distributing, even the looking. Or maybe that’s just me (entirely possible). Maybe curators that put together those shows about some abstract extremely broad subject matter enjoy what they’re doing, and maybe the photographers who get included do, too.

It’s not even that I’m looking for escapism — quite on the contrary. Escapism could be easily had, I would just have to binge watch whatever it is that people currently are obsessed with. What I’m looking for, instead, is beauty.

Creating beauty appears to be such a minor activity. I maintain that it’s one of the most political acts of these times, given that the world the fascists are angling for right now is all kinds of things, but it’s not beautiful. And the fascists have no understanding of what beauty is. If you don’t believe me, just look at and listen to them!

So this book that at first glance would appear to be rather inconsequential — what do photographs of little pieces of art and of a young girl have to set against fascism? — ends up being very consequential after all. It’s a reminder of the fact that contrary to what we are being told left and right, beauty and love are the two things that make life worthwhile. Not power, not money, not dominance.

Zillion was made with love and a fine sense for beauty, and it is filled with love and a fine sense for beauty.

Highly recommended.

Zillion; photographs by Thomas Manneke; 112 pages; van Zoetendaal; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!