Photographs are taken from this world by machines that are operated by the people we call photographers. Despite the fact that there exists considerable artifice in a photograph, causing a rift between what it shows (and how it does that) and the world itself, as viewers we instinctively jump from the picture to the world, coming to conclusions that often (if this were a different essay I’d use “usually”) have nothing to do with the world and everything with us.

By “us” I mean both photographers and viewers. The second major simplification that is commonly made is that somehow, photographers and their viewers are members of distinct, non-overlapping communities. It is true, many photographers, whether they’re photojournalists or the people who call themselves artists, cherish that idea. But the reality is that while photographers take the pictures, their mental (political, societal, …) processing is done by a larger community that they cannot untether themselves from, their frequent noises notwithstanding.

Photographs, in other words, are opinions that might have occasional truth value. For sure, they often don’t reflect our lives reality any more faithfully than the spoken word. We have agreed to suspend this basic fact under certain circumstances. For example, there is an agreement that the photographs used in ID cards are accurate depictions, and people usually don’t argue with the doctors over whether or not a leg is broken when an Xray image shows as much. But look at the worlds of photojournalism and documentary photography to see areas where this suspension is heavily contested.

Things have now obviously got a lot worse as the far right in Western (and other societies) has begun to undermine the idea of truth, to replace it with belief: something is not true because it’s true (meaning: there exists evidence for it), it’s true because dogma (or some leader) decrees it to be true (even if there is ample evidence to the contrary). Thus, global warming isn’t real (it very much is), the US presidential election was stolen (it absolutely wasn’t), COVID is a myth (it very much isn’t), etc.

Kosuke Okahara is a Japanese photographer who originates from the very traditional model of documentary photography, with his work covering larger social issues. Much like many of his peers, his work has taken him to Okinawa, which is Japan’s Hawaii of sorts (for more details, see my review of the Mao Ishikawa catalog).

I suppose when you go to Okinawa as a photographer from mainland Japan, the first question might be: what exactly can you say or do that hasn’t been done many times before? What else is there left to say about the place if you’re an outsider and if you’re possibly wondering about the possibilities and limitations of documentary photography?

In Japan, the idea that ours is just one world, with another one (or maybe more) existing in parallel is never far away. For example, one of the country’s most important holidays centres on the Obon Festival, when families gather and the spirits of their ancestors return briefly on that occasion. I can’t think of a Western equivalent, given that spirits (or maybe ghosts) are not part of our regular culture and now mostly exist as characters in horror movies. The festival is Buddhist. Shinto features a variety of similar ideas, with other types of spirits inhabiting objects.

Whatever you want to make of this, regardless of whether you believe in a world existing in parallel to our own, at their very core such beliefs address the questions of what is real, what is the truth, what can we know? As a documentary photographer, you can’t really ask yourself this question easily because how can you even document something if you can’t be sure that you can arrive at a truth?

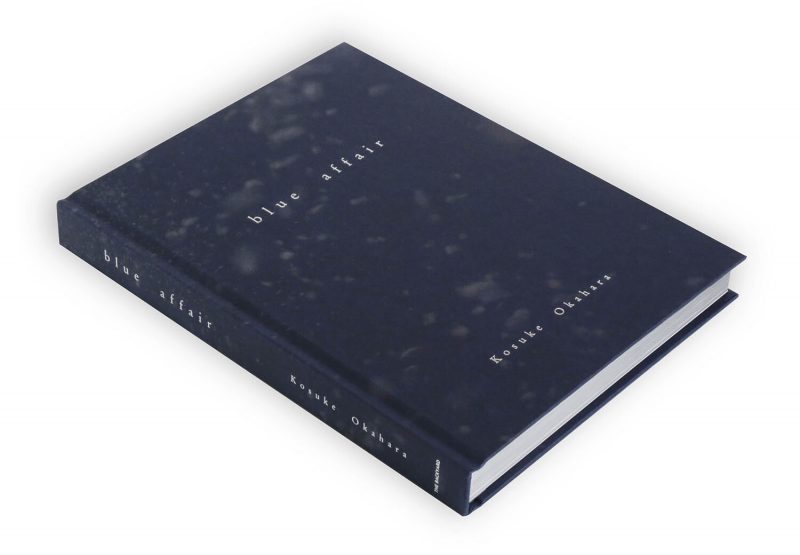

Blue Affair, which exists as a video piece and a photobook, could have easily become your run-of-the-mill documentary-photography project. Instead, Okahara presents the photographs in a very different fashion. The structure of the video and the book is very similar. Given the differences in the media, they play out slightly differently. Still, they’re similar enough for me to describe them in the same way in the following.

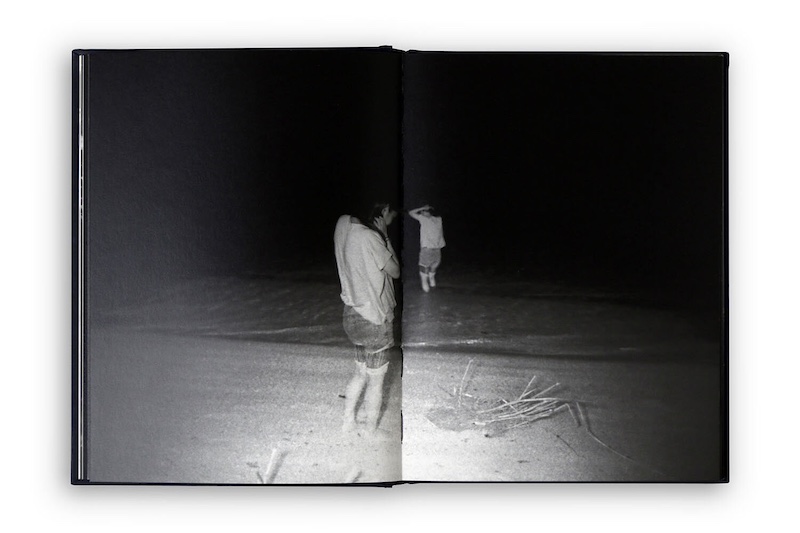

To begin with, there are various encounters with people in Koza, the town in Okinawa Okahara took pictures in. It’s not clear what the connections between the photographer and the people in front of his camera are. For example, there is a couple who, we are told, asks him to come over. When he does, he finds them in the middle of having sex. Why or how this happens we are not told — are they strangers (what kind of strangers call up a photographer to be depicted in the act?), are they friends (same question basically)? We don’t know.

In another brief episode, Okahara meets up with a woman in a dingy hotel room. There, she proceeds to tell him some stories about her life that aren’t revealed. She’s married, she has children. Why or how she would meet the photographer and what else might have happened we are not told.

Other episodes are found, such as when there are a number of people sleeping in the streets, possibly because they’re too drunk to go home (an occurrence so common in Japan that I got used to seeing it during my two trips there). There’s a cock fight somewhere, a woman walks into the ocean, a heavily tattooed woman on psychiatric medication talks about her life…

Each and every of these episodes is introduced in the same fashion, with the photographer saying (in the book, it’s written) “I have the same dream”. Given everything appears to be happening at night, it’s a succession of dreamlike episodes that are clear enough for them to make(at least some) sense. But there are no details, no names, no explanations who people are and/or why the photographer might be dealing with them in the first place. It’s very intriguing.

Kosuke Okahara set out to move beyond the restrictions of documentary photography, and he ended up far away. Both in book and video form, Blue Affair demonstrates how the limitations of photography become a lot more interesting not when you try to fix them (something documentary photographers have to do) but when you embrace them.

Looking at the video and at the book, I feel the heat of the place depicted: it’s hot and humid, and it makes people do things they might regret the day after.

Blue Affair; photographs and text by Kosuke Okahara; text by Tatsuya Ishikawa; 192 pages; self-published; 2020

If you’ve enjoyed this article about photobooks, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.