Okinawa and Hawaii have a lot in common. They’re both mostly known as sunny vacation spots with gorgeous beaches, and they each played a pivotal role during World War 2. But they’re also both latecomers to the countries they now are part of: previously independent kingdoms with their own rich culture, both archipelagos were annexed in the late 19th Century. Their original culture and language were originally largely dismissed (where not outright banned), and they were forced to adapt to being a very small part of a larger culture they originally didn’t have all that much in common with.

Okinawa has been suffering from occupation ever since the late 19th Century. After Japan lost World War 2, vast military bases were constructed by the United States’ military. It is from these bases that bombing runs were conducted during the Vietnam War, and it is these bases that have been responsible for a very large number of sexual-assault cases (there’s a book about the larger topic).

Many Okinawans have long wanted an end to these bases. There have been demonstrations against them for decades. In fact, a large number of (mainland) Japanese photographers have been flocking to Okinawa to make work around this very topic, famously Shōmei Tōmatsu (at this stage, Chewing Gum and Chocolate is the only book still easily available), but also many others. Especially early on, the vast majority of these photographers were male.

Mao Ishikawa is an Okinawan photographer who is known the aficionados of Japanese photography through Red Flower, the Women of Okinawa. It’s visually compelling work that now has taken on some patina, given the time it was photographed. For the work, Ishikawa became a part of the very scene she photographed: bars frequented by US soldiers.

The reality is that there is a lot more to this series of photographs — and, by extension, to the rest of Ishikawa’s work — than you might imagine if you just were to look at the photographs (in particular if you are a Westerner who is not familiar with the larger back story). A newly published exhibition catalogue entitled Bad Ass and Beauty – One Love (T&M Projects) makes this very clear (it was produced at the occasion of a career retrospective at the Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum and has English translations for all Japanese texts).

The catalogue starts out with the photographer’s words. Ishikawa was interviewed by curators Fumiaki Kamegai, Sun Hye Cho, and Fumiko Nakamura. Her answers were then transcribed into a long-form text whose sections address biographical details, general events, and details of the various bodies of work.

Of late, there have been discussions in photoland about who should tell whose story. While there is much to be said for an outsider telling someone else’s story, there is just as much — maybe even more — to be said for a member of a community telling the community’s story. The catalogue provides a very compelling example of why that is the case.

As someone from the Okinawan community (speaking the language, which is distinct from Okinawan Japanese), Ishikawa grew up in the shadows of the US military bases. There were frequent interactions with US soldiers: “When I was in the fourth or fifth grade, my aunt got engaged to an Italian American guy.” (p.13) A little later, she says: “When I was living with a Black GI, we watched a popular TV drama series called ‘Roots’ […] The drama showed the history of the United States’ mistreatment of Black people […] I was appalled but felt that there was some similarity between Okinawan history and that of Black Americans, comparing the dehumanization of Okinawans by the mainlanders to that of Black people by white Americans.” (p.15)

By chance, the photographer was taken to a bar for Black GIs when she wanted to take photos of US soldiers. Ishikawa connected immediately. “I enjoyed myself a hell of a lot,” she says, “which is why I ended up getting great photos. It’s my life. What’s wrong with the storyteller becoming part of the story?” She would use this approach for many of her series, whether when she visited the family of a man she knew from Okinawa in Philadelphia or photographed the families of former dancers in the Philippines.

There obviously is nothing wrong with the storyteller becoming part of the story — if, as in Ishikawa’s case, it’s done from a position of equals and without the power (or privilege) differential that is present in so many other cases we know from the history of photography. In fact, it is this very idea — a storyteller from a community not only has unique insight but there is actually something at stake for her — that is the driving factor behind the discussions I mentioned earlier.

The fact that Akabanaa (Red Flower) occupies only 15 pages out of a total of almost 400 says a lot about how little this photographer and her work are known in the West (and, possibly, in Japan as well, even though I can’t speak to that). A large variety of material emerges, covering traditional Okinawan theater, a portrait of Okinawan fisherman, the aforementioned Life in Philly and Philippine Dancers, a portrait of survivors of the battle over Okinawa (which includes photographs of former so-called comfort women, for which Ishikawa traveled to South Korea), Okinawa and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, and a lot more.

As should be clear by now, Ishikawa’s fearless gutsiness extends beyond her photography: time and again, she tackled difficult topics that for sure must have made her enemies in mainland Japan. I don’t know how Here’s What the Japanese Flag Means to Me was received in mainland Japan. I’m pretty certain that were an American artist to do something similar, conservatives and far-right proponents would be apoplectic over the imagery — imagine Piss Christ on steroids, albeit with a clear political stance.

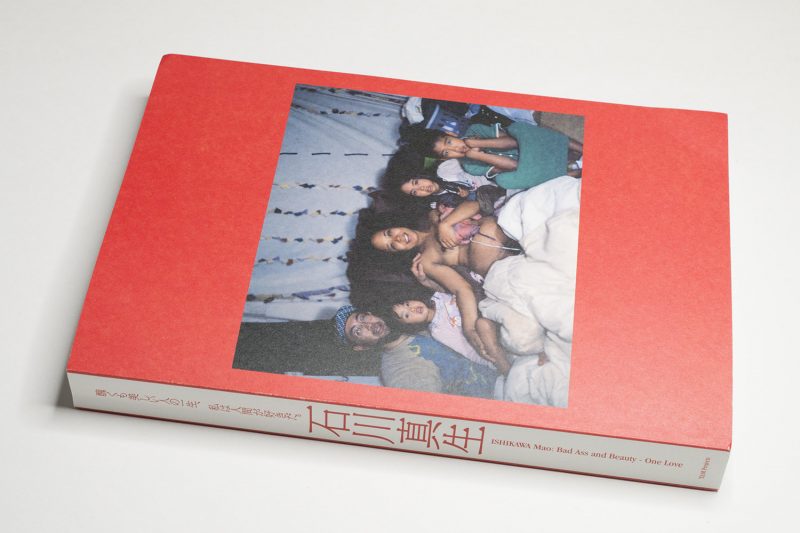

The Great Ryukyu Photo Scroll might be the highlight of the catalogue (Okinawa is located on the Ryukyu islands). In it, Ishikawa re-narrates the history of her homeland, with regular people acting out a large number of historical events. Each photograph comes with its own extended caption (the English translations at times are a bit wonky, which, however, only adds to the sheer playfulness of it all). There’s so much material that there are three photographs per page. I wish these pictures were larger, even though this would have vastly inflated the book (which already has 408 pages). The image on the cover — a portrait of a family right after the mother gave birth — is just incredible.

As far as I am concerned, Bad Ass and Beauty – One Love is an absolute must-read for anyone seriously interested in contemporary photography. It expands the canon of photographers from Japan with a voice from its Okinawa prefecture, and it shows an artist boldly tackling a large number of important topics in a playful, yet completely serious manner.

“I really don’t care if photography is considered a fine art or not.” Mao Ishikawa says, “For me, photography is just photography.” (p.20) I feel that that’s an approach that we can learn something from: photography not as a craft, but simply as a tool to get at larger messages — without worrying too much about what the collectors or curators might think.

Very highly recommended.

Bad Ass and Beauty – One Love; photographs and texts by Mao Ishikawa; essays by Fumiaki Kamegai, Fumiko Nakamura, SunHye Cho, Isao Nakazato, Greg Dvorak; 408 pages; T&M Projects; 2021