After 300 years of self-imposed isolation, in 1868 Japan opened to the world again. The regime, essentially a feudal military dictatorship, was toppled, and a new order was installed. With European colonial powers ravaging neighbouring country — the previously powerful and hugely influential China had been reduced to a hollow shell of its former self, Japanese leaders quickly realised that in order for the country to avoid that fate, they had to adapt. The Meiji Restoration included importing a huge amount of Western technology and know-how. The military was restructured and brought to Western standards, the education system was overhauled, doctors started learning Western medicine… It was a huge endeavour.

Not that Japan had previously not adopted outside knowledge or customs — on the contrary. Japanese is written using a complicated system derived from Chinese characters (in fact, Chinese had played the same role for the pre-medieval elite that Greek had played for the Roman elite: an advanced language that was able to express a lot more nuance than the local language). Buddhism, one of the two main religions, originated in India, with some of its sects being Chinese creations. Guns had been imported using European traders.

But even before the country closed itself of from the outside world, there had been fights over the importance and role of foreign imports. There had been many discussions around how to deal with foreign influences. At various times Buddhism had been attacked as being foreign. Closing the country solved that problem: if nothing new was able to get in, the risk of what we would call a culture war today was eliminated.

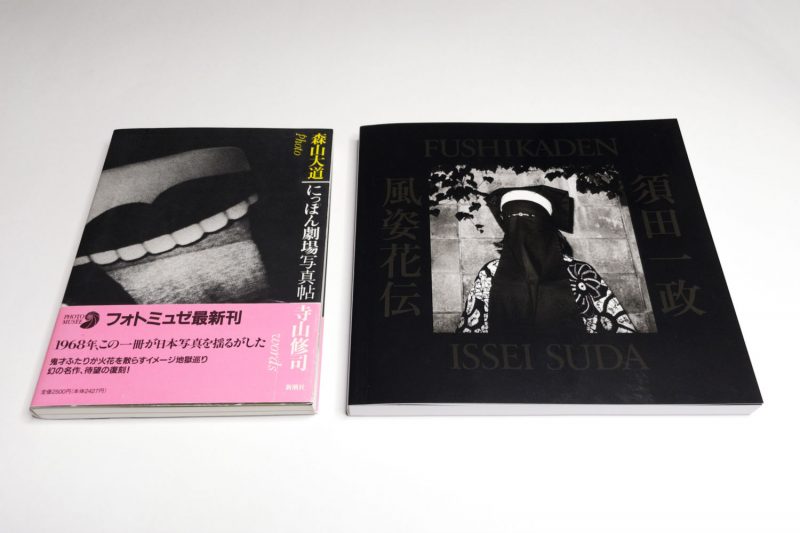

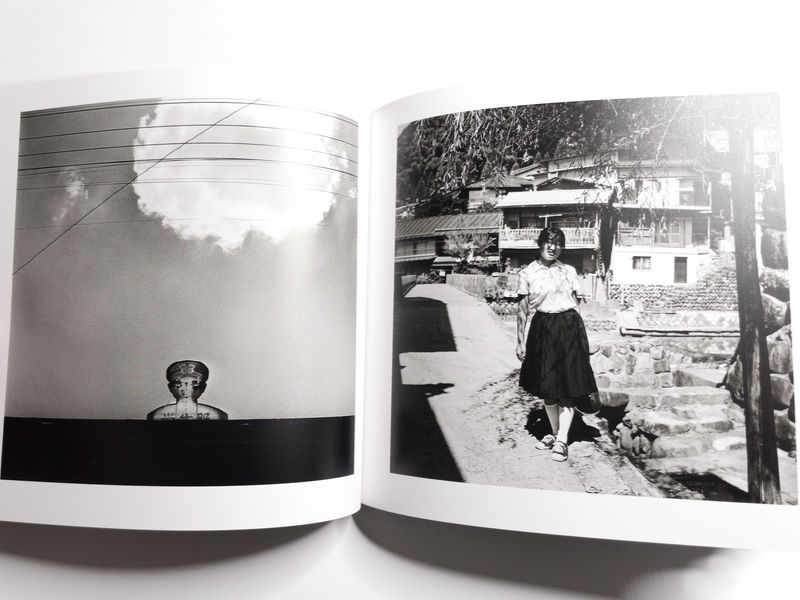

Spread from Suda Issei — Fushikaden

Even before the threat of European colonialism (once the United States engaged in their own colonial endeavours, it added another aspect to this), Japan’s leaders had been enormously fearful of foreign invasions. None of the ones experienced in the past had been successes. Famously, presumed divine winds (kamikaze in Japanese, in actuality a storm) had destroyed invasion fleets sent by Mongol leader Kublai Khan. Thus, invasions, whether actual or cultural ones, loomed large in the Japanese mindset.

In the 1930s, the pendulum swinging between inviting the world in to contribute to Japan and rejecting the outside world to assert Japan’s true values produced the most drastic outcome in Japanese history so far. While the country had engaged in brutal warfare on the Asian continent before (Korea had been invaded), the invasions of parts of China and larger parts of East Asia were mixed with a distinctly modern colonial zeal. After the country’s attack on the US, the pendulum swung back just as wildly and brutally, resulting not only in hundreds of thousands of Japanese citizens being burned alive by incendiary and nuclear bombs but also, later, in the American occupation after the war had ended.

In some ways, after 1945 the Meiji Restoration was repeated, albeit by American occupiers following American rules. The Japanese had very little say in what they were given and in what they had to do. And how could they expect more? They had just lost a barbaric war in which they had committed brutal atrocities in large parts of East Asia. The country was given a modern structure, even as due to the (perceived) Communist threat in East Asia, the US eventually ended up re-installing some of the very war criminals they had claimed they would get rid off. Most notably, the Emperor stayed in place and was not charged at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

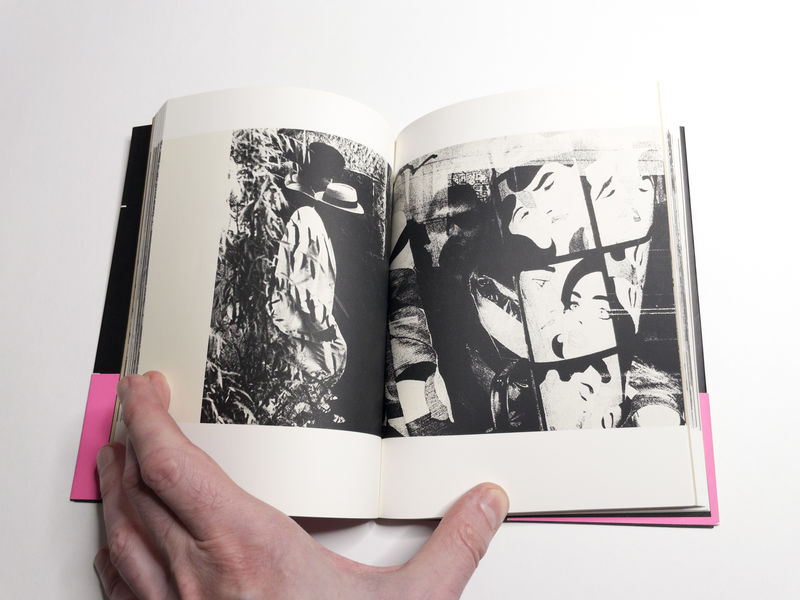

Spread from Moriyama Daidō – Japanese Theater

And so the pendulum began swinging again, albeit in far less drastic terms — at least as far as questions of war and peace were concerned. The question, though, what Japan meant or what it meant to be Japanese re-erupted, with American imports — ideas as much as physical objects — becoming a focal point. The 1960s saw both a rapid expansion of the Japanese economy and fights over whether or not the security arrangement with the US put in place after World War 2 should be kept in place. For the elites, the arrangement was a good deal: the US essentially provided security, meaning Japan would not have to spend much money on its own military.

A lot of Japanese citizens saw it differently. Massive student revolts erupted, and a new generation of Japanese artists started to look at their art and what it meant to be Japanese. It’s important to realize that focusing on Japaneseness not necessarily involved rejecting outside influences, though. After all, young art rebels also rebelled against their own teachers who, in turn, might have had their own, very traditional idea of what it meant to be Japanese or what the essence of Japan might be.

That struggle is reflected in a number of books produced by photographers. In the following, I want to focus on two of the most daring examples of its time, the 1968 Japanese Theater (にっぽん劇場写真帖) by Moriyama Daidō (森山大道; born in 1938) and the 1978 Fushikaden (風姿花伝) by Suda Issei (須田 一政; 1940-2019). Both books originated from work that had been serialized in photography magazines before. Those interested in the important role magazines played for Japanese photographers will find all the information in Japanese Photography Magazines: 1880s to 1980s by Kaneko Ryūichi, Toda Masako, and Ivan Vartanian. Following Vartanian and Kaneko’s use in their earlier Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ‘70s, throughout this text I will refer to Moriyama’s debut book as Japanese Theater instead of the commonly used Japan — A Photo Theater.

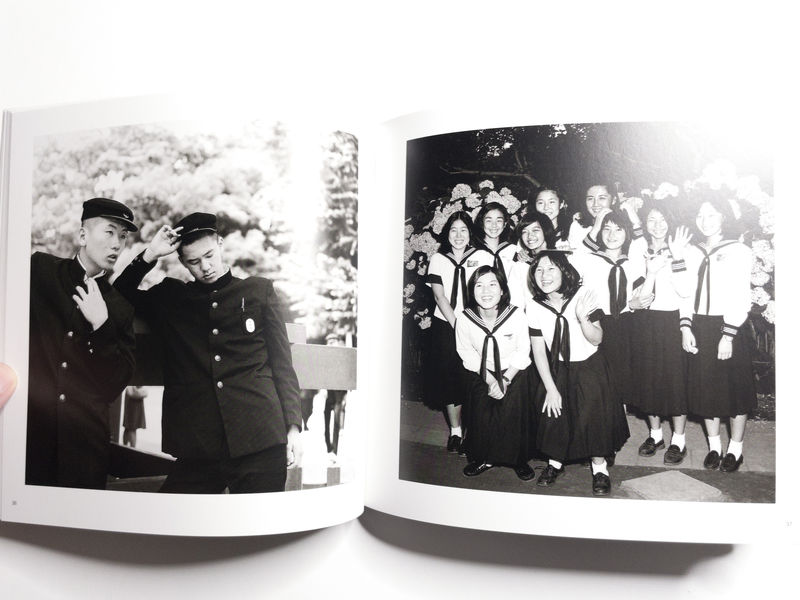

Spread from Moriyama Daidō – Japanese Theater

After all, contrary to what is widely seen as the focus of this photographer’s work, the book does in fact center on Japan itself. In fact, Japanese Theater is a truly essential book. It is possible to read it as a lot more than a photographic exercise. With such a read, Moriyama’s early work is being brought back to some of the contexts it was made in. Furthermore, the read allows for its at times feisty takes on Japan to come to the fore.

Both books have been reissued a number of times. I do not own copies of the original editions. Instead, I have two versions of Japanese Theater, a 1995 version and a 2011 one. Both maintain the original edit and sequence. But both deviate from the original in the chosen layout. The 1995 version adds blank space above and below the photographs (this version is shown in the photographs). The 2011 version returns to the original full bleed but contains some at times drastic layout changes. Pairs of pictures from an original spread might be broken up into singles. And there are at least two occasions where a single photograph was reproduced over two separate spreads.

I also own two versions of Fushikaden, one from 2020 and the other from 2024. As far as I can tell, the 2020 version does not contain the full set of photographs from the original. In contrast, the 2024 version contains an additional 38 photographs that had not been included in the original (an afterword written in 2012 by the photographer makes it clear that he approved of this change).

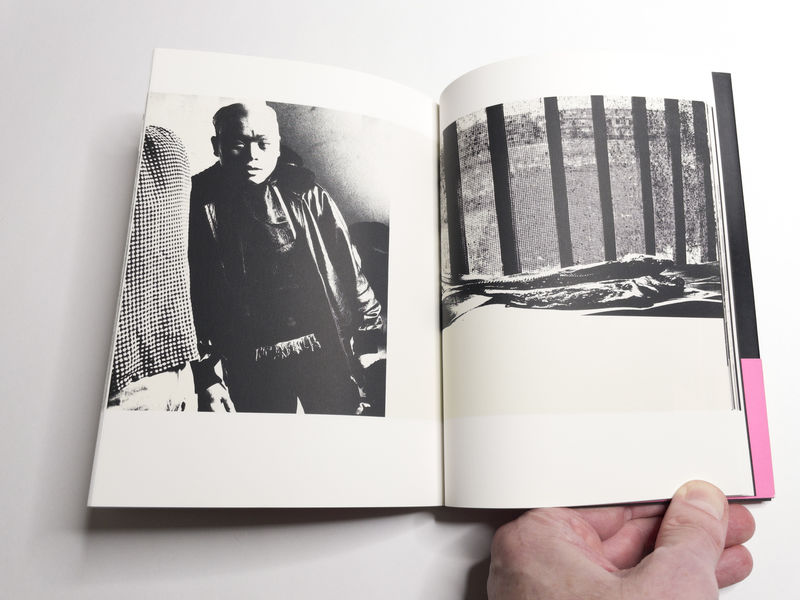

Spread from Suda Issei — Fushikaden

Unlike the photographs published in Moriyama’s later books, the material in Japanese Theater is incredibly heterogeneous. Provoke style photographs flow into street photography, which in turn flows into the documentation of avant-garde theater groups the photographer spent time with and worked for. With the later books in mind, Japanese Theater does in fact feel fragmented and jarring. However, it would be a mistake to dismiss it as early work by an artist who had not reached his artistic maturity, yet. It is true that Moriyama was experimenting, often drastically, such as when he re-photographed images from posters or other media. At the same time, despite the differences in the photographic approaches, a very genuine curiosity for the country he was (and still is) living in shines through the book.

Placed into the context provided by the book, everything becomes a theater: a performance enacted for effect, albeit not always for an audience. It is actually the photographs of the avant-garde theater groups that appear tamest next to the other material. Their nature of producing documents has the viewer focus past the photographs on what’s on display instead. The very first photograph in the book — presented smaller than the rest — shows Isamu Shimizu, an actor, perched on a chair — as if wanting to invite the viewer to the show that is due to unfold over the rest of the book. Shimizu comes across almost as an equivalent of Pee Wee Marquette, the Birdland MC who would introduce a number of Art Blakey albums on Blue Note between 1954 and 1960 (here’s an example).

And then the show unfolds with its rapid-fire sequence of photographs, some helter-skelter, others less so. There’s an abundance of symbols to give away the times and the place: there are Japanese flags (the post-World War 2 one and the older one), and of course, there are frequent depictions of members of US military forces. Crucially, the Japanese people themselves are shown in any number of ways, whether wearing traditional attire, Western dress, or they’re dressed up to perform their avant-garde theater.

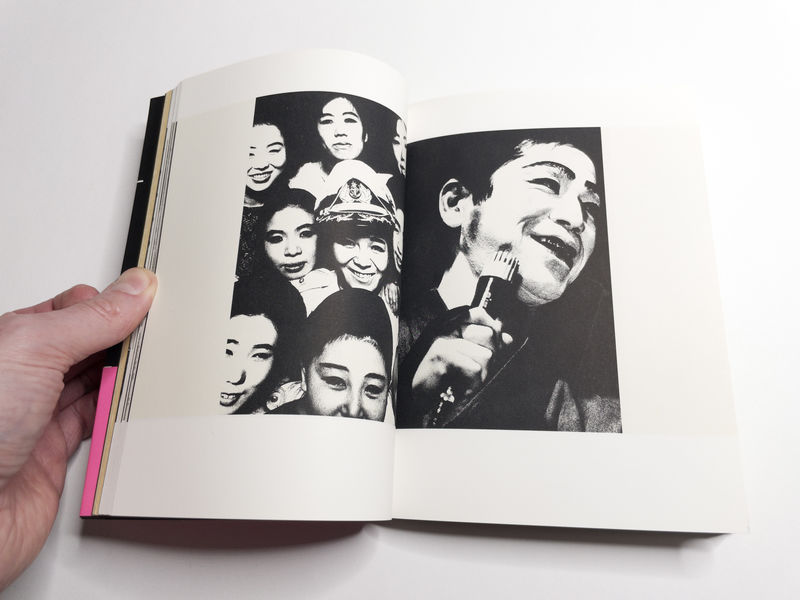

Spread from Moriyama Daidō – Japanese Theater

If it is not clear what exactly the Japanese are standing for or who they are, that is precisely the idea of the book. Moriyama doesn’t appear to be taking sides, either, instead following along and recording with the detached approach he became known for. The viewer is constantly being thrown around the different faces of Japan, with the effect that at some stage, the normal looks crazy, and the crazy looks normal. It’s a very free-flowing approach to making a book, one in which there is no real narrative. You end up with what in German is called a Stimmungsbild: a visual depiction of a mood. But unlike in Moriyama’s later books, it’s not the photographer’s mood. The “hunter” persona he would adopt later (in fact there even is an eponymous book) had yet to emerge. And it precisely that fact that makes Japanese Theater more effective than any of the later books (and most certainly the most recent ones, in which Moriyama in effect has become his own cover band).

On a photographic level, Suda Issei’s Fushikaden is much simpler. Even as the photographer did experiment considerably with the cameras he used, for his different projects he mostly used one tool, in this case the square format with the occasional use of a flash (there are a few non-square pictures in the 2024 edition of the book, which I’m pretty certain were part of the later add-on). As the list of photographs in the back of the book makes clear, Suda photographed all over Japan.

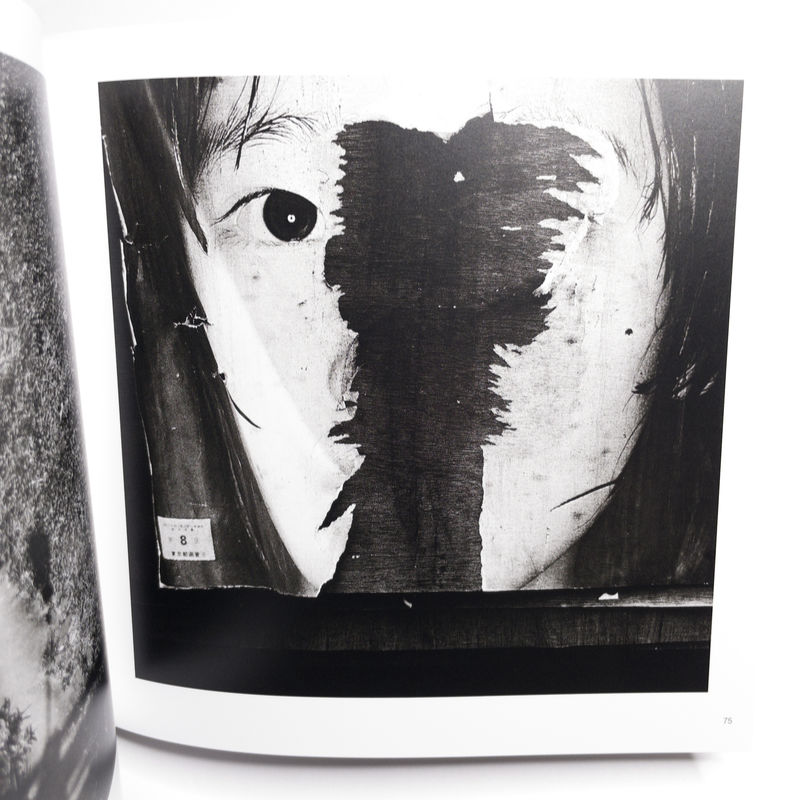

A few of the photographs appear to have been taken at any of the country’s frequent and still common summer festivals where visitors wear yukata (a light and less complex kimono) to watch performances of music and processions. Some of the most jarring photographs feature tightly cropped closeups of performers or observers. What in real life would merely be a person performing in the context of a larger festival, through the framing and often through the use of flash is transformed into an actor on their own — or rather Suda’s stage. Much like in Japanese Theater, these performance photographs pull the other ones into the same realm: suddenly, everyone is performing a role, and the whole country becomes its own slightly strange play.

Photograph from Suda Issei — Fushikaden

As in Japanese Theater, the traditional mixes with the modern and slightly premodern. Despite the relative photographic uniformity, with Fushikaden Suda ends up creating the same atmosphere Moriyama did in his debut book. We encounter a country that manages to be at peace with itself while being engaged in a struggle over its own identity, a country that desperately wants to embrace all that is new while clinging on to its ancient traditions, a country that simultaneously is insecure and overly confident. This certainly is not a uniquely Japanese predicament: watch Germany struggle over what it wants to be or any of the other nations currently stuck at some stage of the theater of fascism (with Japan’s politics essentially frozen in the place after World War 2, the country has so far managed to avoid going down that road).

Suda took the title of his book from Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443), who played an essential role in the creation of Noh theater and who wrote material about it, notably “The Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style” (Fushikaden). In fact, in the late 1960s Suda had photographed avant-garde theater himself, working with the same Terayama Shūji (寺山 修司; 1935-1983) who had also pulled Moriyama into his world (he wrote the text that is contained in Japanese Theater). There even was a joint book produced in 1968, which, alas!, is hard to come by.

Thus, in light of both photographers’ involvement in the world of Terayama, the emergence of the two books does not come as a surprise. That they would both pick up on the cultural and societal convulsions of the newly emerging consumerist Japan also is not quite as surprising as one might imagine: great artists are able to pick up on the movements of their society’s shifting tectonic plates (see Robert Frank’s The Americans or Michael Schmidt’s Ein-Heit).

What is remarkable, though, is how these seemingly so different photographers both produced variations on the same theme. It is almost as if they had had an arrangement to make the same book, one in which the seeming certainties and denied uncertainties of late 1960s/early 1970s Japan were going to put on full view and in which the country itself was being transformed into one gigantic playhouse where every street and every alley was transformed into a stage. Interestingly, despite the vast differences in these two photographers’ personalities the two end results are very similar in spirit, and they both refuse to provide answers.

What is Japan? What does it mean to be Japanese? Where will the country go?

Who knows.

And who cares?

The pendulum will keep swinging.