At the occasion of an exhibition of Nobuyoshi Araki’s work in Vienna in 1997, Austrian critic Christian Kravagna wrote an essay entitled Bring on the Little Japanese Girls! Araki in the West. Its premise was a very simple question: “How can someone’s photographic practice so obviously based on the commodification of the sexualised female body be acclaimed in a context that has become highly sensitive to the representation of gender power relations?” (in Autumn 1999, the essay appeared in the journal Third Text 48, now hidden behind a paywall, p. 65). This is a very obvious question, isn’t it? Yet here we are: at the time of this writing, there’s yet another Araki exhibition in Vienna. And it would be unfair to single out Austria, because the photographer is still being widely and pretty much almost completely uncritically celebrated in the West. Now, though, curators will occasionally call him a “controversial photographer”. Controversial is good, of course, because it helps move tickets.

In his essay, Kravagna offered a number of possible explanations for why Western curators and critics were unwilling and/or unable to realize that they had (and still have) a problem at hand. Araki’s work is very obviously caked in misogyny, yet the bulk of Western photoland simply won’t deal with that. How is that even possible? “Doubly fascinated with cultural difference and the unfathomable in female sexuality,” he wrote, “literature on Araki fits into an old pattern that links exoticism with erotism”. In other words, according to Kravagna, we’re dealing with old-fashioned Orientalism: “Not only does the image of women conveyed in the West through Araki’s photographs largely correspond to these fantasies, these fantasies are confirmed when one finds them in quasi-approved form at the level of art.”

In Representation, Distribution, and Formation of Sexuality in the Photography of Araki Nobuyoshi (positions 18, 2010), Hiroko Hagiwara picked up the thread from Kravagna and developed it a lot further. I suspect that if this article weren’t hidden behind a corporate paywall, photoland would look at Araki differently (or maybe not, I’m often too naive). While there is a long discussion about how to discuss the photographer’s male gaze, the Japanese critic also dives into the perception of Araki in the West. Commenting on often expressed remarks that tie Japanese bondage (which Araki obsessively photographed) to the country’s tea ceremony (and other local customs: bonsai, ikebana, etc.), she writes: “Such a touristic facade of ‘traditional’ art will never provide a contemporary photographer with a metaphorical frame to critically express the rigidity of Japanese society.” (p. 243)

Consequently, people who are very aware of the risk of violating cultural differences end up shooting themselves in the foot by unwittingly applying the very kind of thinking that they hope to work against: Japan is just different, so we can’t apply the same standards. Too afraid of violating cultural differences, essentially neo-colonial ideas serve as a fall back (as both Kravagna and Hagiwara point out). However, the reality is that while there are cultural differences between Japan and, let’s say, the United States, misogyny in Japan is not all that much different than misogyny in the US, even if it might manifest itself differently. The same is true for many other aspects of life in Japan and the US. But the idea of Japanese otherness is just too convenient, even in circles that in principle (should) know about the perils of othering.

Obviously, we wouldn’t be in this situation if we had more access to Japan’s cultural world. As it turns out, there currently is a mini-boom of books written by female Japanese novelists published in translation. If you want to learn more about Japan through novels, put aside Haruki Murakami (whose novels are also caked in misogyny) and check out any of the writers mentioned in this article. If you want to learn more about Japan through its visual arts, then… well, you’re a little bit in trouble.

If we stick with photography, what’s being offered in the West is very limited. It’s either yet another exhibition by Araki or by the other famous old man, Daidō Moriyama. Or if you’re lucky, there is a themed exhibition around something that unfortunately makes it hard to see Japan as just an ordinary country. A good example would be an exhibition like In the Wake. There was some incredible work in the exhibition. On the other hand, I wager that if people remember an artist (big if), he or she will now be seen as being well known for her or his tsunami work. I should note that there exist some pockets in photoland that try to work against the representation of Japan as a profoundly other country and that try to present a wider range of names and topics. For example, at SFMOMA Sandra Phillips has been instrumental in bringing a wider view of Japanese photography to the US.

I should note that Japan isn’t the only country that is seen in a very strange light in photoland. Once you start looking into photography made in pretty much any of the countries south of the United States or in Africa — both huge continents with a large variety of cultures and customs, you’ll run into the very same problem. Don’t believe me? Well, then name a Senegalese photographer, and tell me something about their country and work.

The key to moving away from simplistic ideas about other countries and their cultures is to move towards a more varied and inclusive representation of their art. In the context of Japan, this means that we desperately, desperately need less Araki or Moriyama exhibitions (or books) and more by any of the other brilliant photographers — whether they’re of the Araki/Moriyama generation (now either dead or in their late 80s) or the many, many younger artists working there. And exhibitions should not be themed. I know curators love themes because they’re easy to work with. But themes only invite the problems that I discussed in the above.

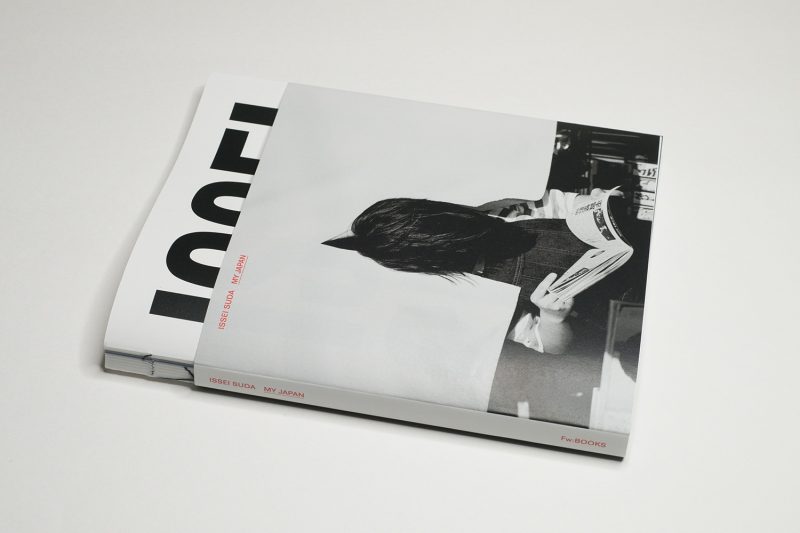

This brings me to the exhibition of work by Issei Suda at FOMU in Antwerp (Belgium). “Issei Suda (1940-2019) is a famous name in the world of Japanese photography,” the museum writes, “yet he remains relatively unknown in Europe. FOMU wants to change this with a first retrospective of his work outside Japan.” My Japan, a catalogue of the exhibition is available through FW:Books (I will use the catalogue for my discussion).

The bulk of Wikipedia’s page about Suda is taken up by a list of his books. This reflects the photographer’s obscurity in the West as much as the fact that the book was (and still is) the main outlet to present work in Japan. At the same time, however difficult it is to get access to Japanese photobooks, for many artists, they are the only type of access a Western audience has.

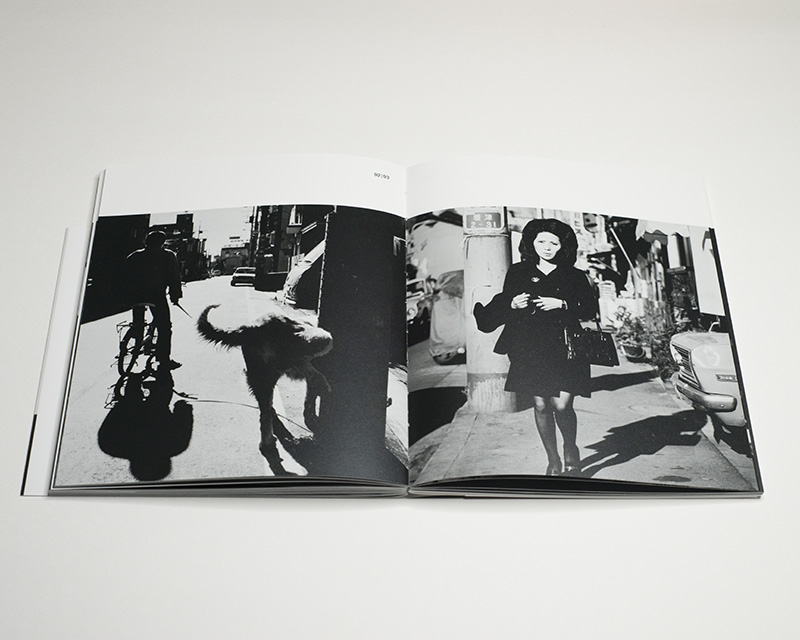

The two earliest books listed on Wikipedia, Fūshi kaden (風姿花伝) and Waga-Tōkyō hyaku (わが東京100), demonstrate an artist at the very top of his game (it’s important to know that the dates of Suda’s books do not necessarily reflect when their pictures were actually taken). Photographs from Fūshi kaden and Waga-Tōkyō hyaku feature prominently in My Japan (in the catalogue, Fūshi kaden is written as Fushi Kaden; much like German umlauts, details such as denoting a long vowel — ū instead of u — often get lost when Japanese words or names are transposed into Western script).

For these and a number of other series, Suda worked with a square 6×6 camera, occasionally using flash as well. The photographs often are what we think of as street photography, even though Suda mixes such photographs with a number of other details from his wanderings. There’s an interview conducted by curator Frits Gierstberg at the end of My Japan, in which the photographer reveals his thinking of the work: “I’m afraid I have no respect for those whom I photograph. I always shoot them as a reflex. […] My manner of shooting people without permission might be rude. […] Nobody was suspicious of photographers in the 1970s, the time when I shot Fushi Kaden.” (p. 136)

Whatever you want to make of Suda’s sentiment here, the fact that these series mix a number of approaches lifts them out of what we’ve come to expect from Western street photography. The majority of the photographs in both Fūshi kaden (風姿花伝) and Waga-Tōkyō hyaku (わが東京100) are absolutely incredible, and they deserve to be seen and appreciated much more widely (I’m lucky to own a copy of the 1979 release of Waga-Tōkyō hyaku so I know the full set of pictures).

If you look through My Japan, you’ll encounter a country that feels somewhat familiar to some extent (through those very cultural markers that are so well known: kimonos etc.). But there also are a lot of other aspects that show a country that is not very well known: the ordinary Japan. There are many pictures of ordinary life, unremarkable moments made remarkable through pictures. All of this is seen through the eyes of an incredibly gifted photographer who despite the generation he belonged to (with its very strong sense of machismo) managed to reveal very tender moments as well.

Obviously, Suda’s Japan isn’t Japan any more than Araki’s or Moriyama’s is: it’s the artist’s (hence the title of the catalogue). It is only through the combination of looking at a country through a large number of eyes that its essence might reveal itself. Ideally, there will be a lot more exhibitions like the one currently on view in Antwerp, bringing a lot more Japanese (male and female) artists to the West. That way, our often simplistic view can finally expand beyond Araki’s misogynistic freak show and Moriyama’s by now incredibly stale Beat photography.

One last comment: My Japan is priced at €20,00. That’s a great price to entice someone who might not be too familiar with this photographer’s name and who might be reluctant to spend a lot more money on a book. It’s a small, unassuming book, and as is always the case with FW:Books, it’s produced incredibly well.

Highly recommended.

My Japan; photographs by Issei Suda; interview with Frits Gierstberg; FW:Books/FOMU; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article about photobooks, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.