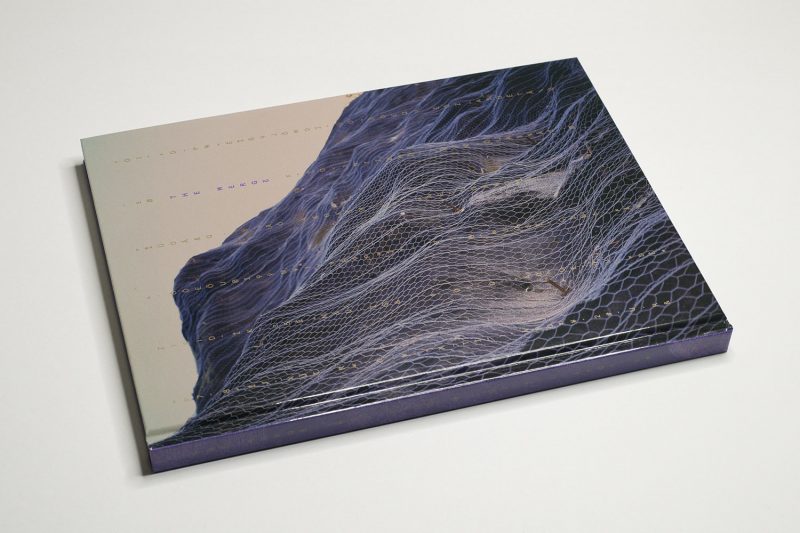

What happens when you’re trying too hard to be clever, when, in other words, you’re so enthralled by your own wit and ingenuity that the outcome telegraphs those more than anything else? Every time I pick up The Merge by Sara Brincher Galbiati, Peter Helles Eriksen, and Tobias Selnaes Markussen, my mind is drawn to that question more than to what the photographs in the book might be getting at. In many ways, this makes it difficult to write something about the book. I will try regardless.

The book’s makers aren’t helping themselves with the inclusion of a text that comes a few pages into the book. The idea of the text is to explain to a reader that we might be living in a computer simulation. This is the book’s focus: are we real? Do we exist? (I’m simplifying this a bit but not all that much.) That in itself might be a worthwhile topic to think about. But it’s conveyed rather clumsily and in a fashion that, well… That’s where the “trying too hard to be clever” bit enters.

You see, I have a background in theoretical astrophysics. I met quite a few incredibly intelligent people who believed in pretty mind-blowing stuff. When I use the word “believed” I don’t mean this in the sense of a religion. Theirs was not a faith. No, they could prove to you that what they told you was if not likely to happen then at least a very reasonable theory.

For example, I once met Frank Tipler. Tipler thinks that “a society in the far future would be able to resurrect the dead by emulating alternative universes” (quoted from the Wikipedia page). He derived this idea in a scientific fashion. But when I heard him speak, I never had the impression that the cleverness of this idea was of any concern to him. It was simply logical (to him anyway).

The problem with such theories is that only those that are deeply embedded in the field can fully understand them. Everybody else inevitably can merely get the gist of it, which might or might not be coming from a book that attempts to popularize the topic for a mass audience (which is a pretty lucrative business by the way). And that’s fine.

For example, I know various aspects of theoretical astrophysics pretty well. I worked on computer simulations of the Universe. Even though this is part of my past, I think if I were to somehow decide to create a photography project on simulations and/or the people who produce them (which, don’t worry, I won’t), it would come out pretty good. But I only have a very surface understanding of, let’s say, mRNA vaccines (I received one, for which I’m intensely grateful). I could probably read up on them. But if I were to decide to produce a project on such vaccines, I’m pretty sure it would result in something that’s rather cartoonish (at least for those people who know more about the subject).

In other words, while I understand the appeal of creating art around advanced scientific ideas, there is a problem with artists doing that. They typically gravitate towards two possible outcomes. They get too drawn in to the point where you can see they think they’re almost a scientist. I once had a very well known German photographer explain astronomical image processing to me. I didn’t have the heart to tell him how wrong parts of his understanding was. Alternatively, they end up being too enamoured by their own cleverness.

In both cases, the outcome isn’t what they set out to do: art. At worst, it’s entertainment that masquerades as art. Art, after all, encompasses the viewer’s imagination, and it does so in a way that’s not prescriptive. Thus, it’s not enough if an artist uses her or his imagination. The viewer also needs to be given the same opportunity. Her or his or their imagination must be allowed to run free — instead of being told “hey, why don’t you think about this and only this?”

There is another aspect of the book that also ties in with something that I have been grappling with for a while. In my book Photography Neoliberal Realism, I use Andreas Gursky as one of the main examples. Gursky’s work is instantly recognizable for its portrayal of ant-like human figures in an enormous, overwhelming world that is governed by forces beyond the control of any of these figures (the fact that most of his pictures are constructed in a computer is irrelevant).

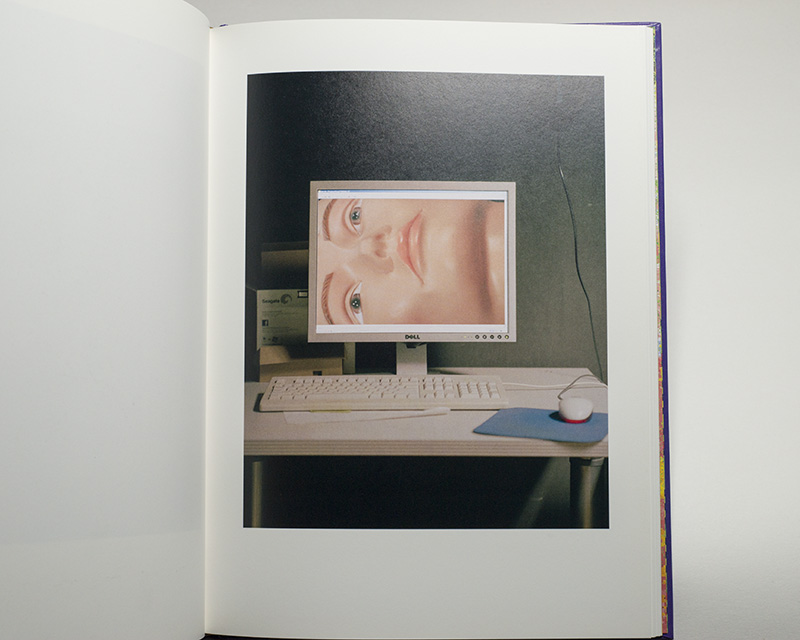

For reasons of space (the book’s intended target length) and time (the deadline), I didn’t dive into an aspect of Gursky’s work that is very important. It’s not just the sublime in its classical form that this artist is playing with. More often than not, it’s the technological sublime, one of the handmaidens of neoliberal capitalism. The technological sublime is a tempting target for photographers, simply because modern technology evokes it quite naturally.

In the past, the technological sublime mostly addressed the physical sense and only if you were actually present at the scene. If you look at, for example, Eugene Smith’s photographs of steel mills, they cannot really convey the heat and noise of those environments. But today, things have shifted. If you see how, let’s say, cars or computers are produced today, you’ll encounter incredibly clean looking environments that are great for photographs. Often, robots play a role in the process (again, great for photographs).

In other words, post-post-modern technology and the places where it is made differ in terms of how we relate to them compared with their modernist predecessors. Whereas it was pretty straightforward to produce deeply critical work around the labour conditions of workers in the modernist era, it has become a lot harder now, given that there is the temptation to essentially produce neoliberal realism around the factories (just look at Edward Burtynsky’s photographs from Chinese hi-tech factories).

Another way to describe the problem would be the following: during the 1920’s someone praising modern factories and someone criticizing them would have produced very different pictures. Today, their pictures would probably look identical.

So when I see a photograph of a man sitting in an oversized somewhat anthropomorphic computer in The Merge (roughly halfway into the unpaginated book), I’m looking at a form of the technological sublime of the early 21st Century, which, as I already noted, plays a huge role in Neoliberal Realism. There are many other photographs in the book that operate in just the same way.

I suppose it’s fine to think about whether we live in a computer simulation or not. I’m personally not all that interested in the idea. I am able to imagine how an artist (or an artist collective) could get me interested in that. However, I don’t think you can do that by producing something that just feels too clever and that also seems blissfully unaware of how large parts of the imagery feed into Neoliberal Realism.

After all, once I see that, I’m wondering why we’re talking about whether we live in a simulation when we could instead talk about the uses of all that technology depicted in the pictures. Even if I’m just some part of a huge simulation, I’ll never be able to escape that fact. So I might as well deal with the other parts of the simulation that effect my life, right?

And if I’m not a part of some huge simulation, it feels like a strange luxury to me to ponder about that while a little over 100 miles from where I’m writing this, a group of engineers build anthropomorphic robots (that we all know will find their first uses through the military to kill people), only to also produce pretty scary videos about what those robots can do, videos that make it clear that these engineers are unaware of the problem: “hey, look at our future killer robot dance!”

I know the inevitable retorts to the above (which I’m cool with): why should artists be only critical? Can’t they just “explore” something? Why would they have to challenge the status quo? These questions have considerable merit. Every single artist should simply be doing what she or he or they feel like doing.

But when the sum of it all — the community — largely fails to respond to all the various challenges to our societies, democracies, and well being, then I’m left to wonder where it all went wrong.

Maybe it’s simply the fact that the world of art has become too enmeshed with the very people who are responsible for the challenges I just mentioned. Why or how? Simply follow the money.

The Merge; photographs and text by Sara Brincher Galbiati, Peter Helles Eriksen, and Tobias Selnaes Markussen; 136 pages; RM; 2020

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.