Sandwiched between two perpetually murderous nations (Germany and russia), Poland has had its fair share of tragedy over the course of its history. It is situated at the western edge of the region termed Bloodlands by historian Timothy Snyder who described the reign of destruction inflicted by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. At various points in time, Poland ceased to exist as a state, having been parceled up and incorporated into neighboring empires. No surprise then that national identity and history — mind you, the writing of it — play an enormous role in Poland.

This became especially clear during the recent reign of the neofascist PiS party that sought to re-define history (as all neofascist parties do) to further the country’s glory, elevating any number of odious characters (ditto) and demonizing its neighbours, which, granted, had brought much destruction to Polish lands. Of course, given how bad it had been that destruction did not need any PiS efforts to talk it up. And PiS’ embrace of some of the more odious aspects of Polish history also did not reflect well on the country.

But neofascism isn’t interested in historical facts or truth: it’s interested in a glorified past that aligns with its ideology, and it’s interested in constantly whipping up voters’ resentment. Resentment drives the neofascist project, in particular the ideas that a) people voting for neofascist parties somehow are overlooked, ignored, and/or forgotten while others reap the benefits (cue the inevitable racism and antisemitism) and b) the country needs to go back to a glorious past that has been betrayed by “elites” in power.

Even without the neofascist project history is constantly being re-written and adjusted. This is not just because there might be the occasional new discovery, whether archeological or otherwise. But people’s thinking also evolves. A few hours ago, I visited a village just to the north of where I am writing these words. In one of the historical houses, one of the volunteers bombarded me with details about the various rooms none of which I retained, simply because I was so struck by her use of “we” and “the English” — as if somehow this was still the 18th Century.

In a different building, a museum, you could easily discover updates to the various displays. A number of stone plaques, created to memorialize people (colonial settlers) who had lived there, had been covered up with cloth ones: the language had been changed in order to reflect today’s sensibilities. A corner now contained word of the role of slavery in the village, and various items had been removed from vitrines and replaced with signs that they were now being looked at to determine whether it was culturally sensitive to still display them.

History, in effect, does not exist. History is always an exercise in ideology, however benign one might imagine that ideology might be. It is the telling of history that reflects what a country believes about itself, and for me, that is one of the most interesting aspects of history (because, let’s face it, the re-telling of most historical facts — usually endless names of rulers — is mostly very tedious).

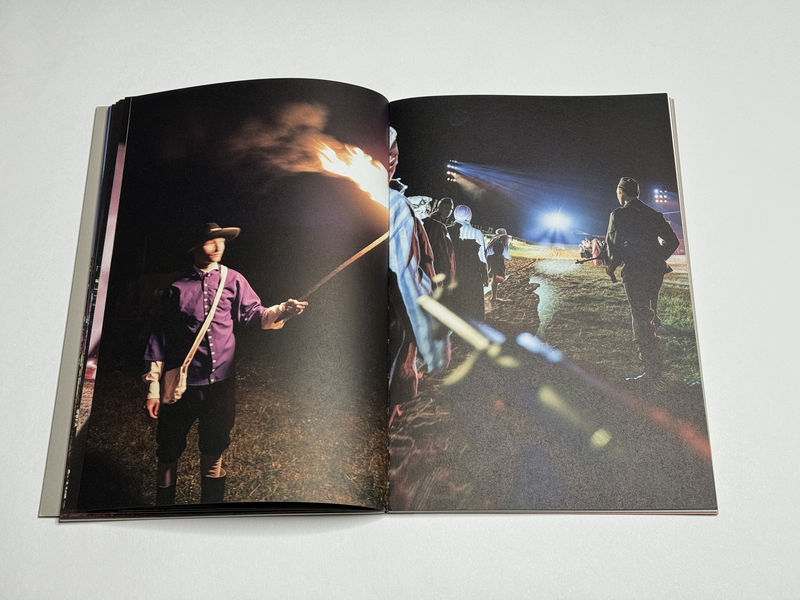

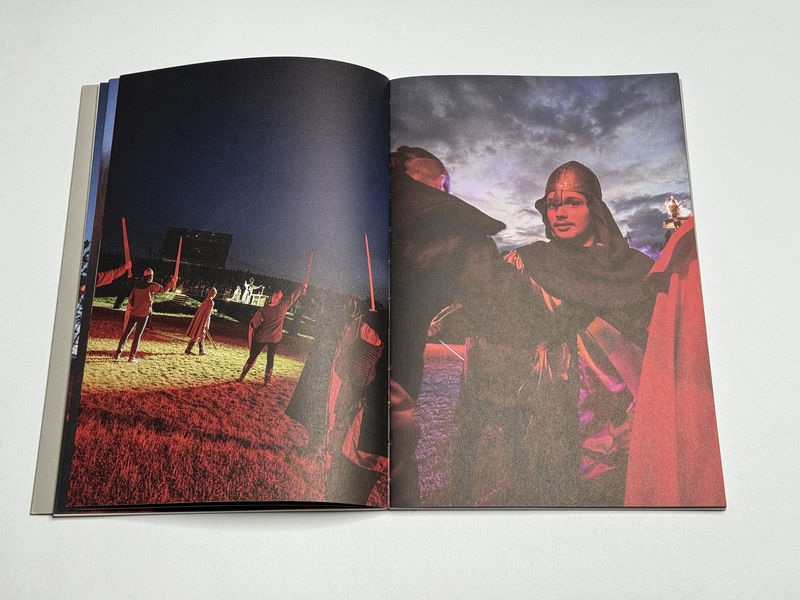

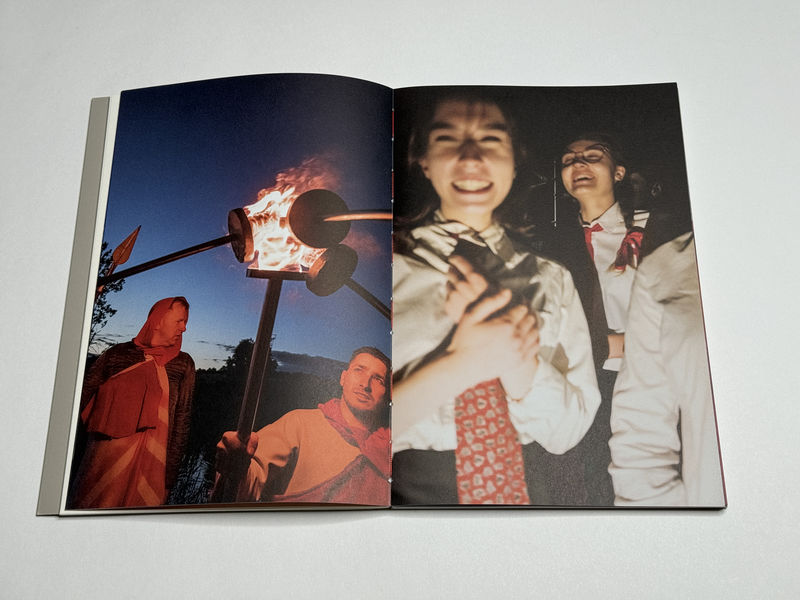

By construction, there is a certain cartoonishness to historical reenactments. Everybody knows that it’s costumes, and everybody knows that those wearing them typically live much more comfortable lives than the ones they pretend to exhibit during the shows. Furthermore, the selectiveness of their historical narration is amplified through the spectacle itself, which, of course, has to be entertaining for spectators.

With all of the above in mind, historical reenactments really are not about the past. They’re about the present: they reflect what people want to believe in. And that’s why they can be so interesting. Over the years, I have seen a number of photography projects about such reenactments. The problem with such projects is that it’s so easy to get the pictures, but it’s so hard to make them about more than the costumes. It’s the costumes, after all, and possibly the fake blood that will get all of the attention.

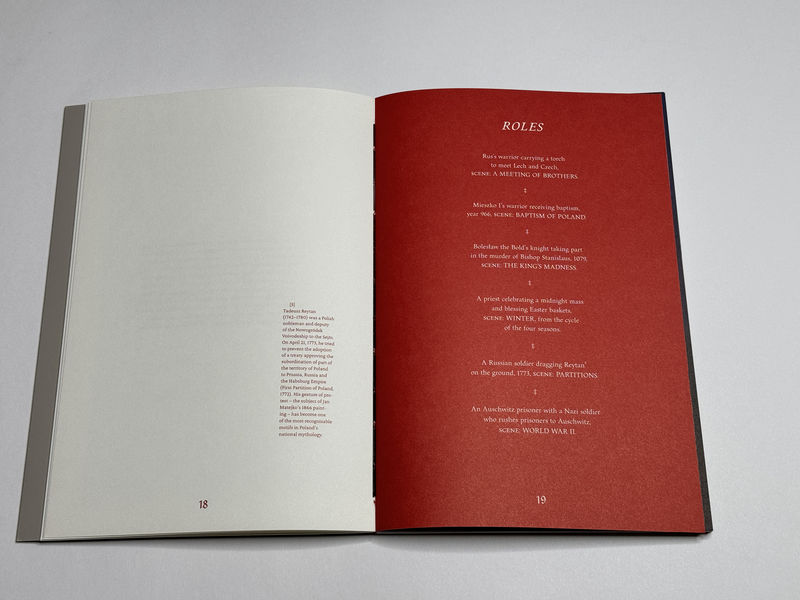

Michał Sita‘s History of Poland Vol. 2 differs from such project for two reasons: first, there is added text, words spoken by some of the reenactors. Second, and crucially, Sita himself was one of them, wearing a camera around his neck during the proceedings (the camera took a photograph every second, and while it was not visible for spectators, the other reenactors were aware of it). There also are a few other photographs that look as if they were taken with a different camera.

The show in question is called The Eagle and the Cross, and it’s happening in Murowana Goślina, a small town in western Poland, just north of Poznań (which, if you don’t know, sits about in the middle between Berlin and Warsaw). The show feature six separate chapters, starting somewhere in the Middle Ages and ending with a Nazi soldier sending prisoners to Auschwitz (the book explains some of the events and characters).

I was particularly struck by one of the text sections in which a volunteer actor imagined how one of the thousands of Polish officers murdered by Soviet soldiers in Katyn might have faced his death. It is clear that the actor does not have the unnamed officer in mind. There might not have been a specific officer anyway, a person with a family. No, it’s an unknown officer, one whose death will later play a role when both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union will accuse each other of the massacre.

And of course, the death also plays a role in the play: yet another, very different role. “Pride,” the actor imagines, “is not a smile, but rather a grimace showing that he is no longer afraid and is ready for what is about to happen.” “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” the Roman poet Horace had already written two millennia earlier: “It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country.” But it’s not just sweet and proper, you also have to go about it with pride so that your death might serve those who survive or live later.

There is something unsettling about a book that lays out so clearly how the past is made to serve contemporary purposes. But it’s an important book, especially given the fact how the past has become weaponized by the neofascists — in Poland as much as in the US, Germany, Hungary, Italy, russia (the movement’s center), and elsewhere. Even as it’s important for us to understand the past, it’s equally or possibly even more important for us to understand to what end we want to understand it.

History of Poland Vol. 2; photographs and text by Michał Sita; 96 pages; Sun Archive Books; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!