One of the biggest disappointments for me as a child was the fact that the city I grew up in didn’t have much of a history. As an adult I now know that there actually was plenty of history for a place that had been founded in the late 19th Century. But children aren’t interested in, say, sailors’ mutinies that lead to revolutions. Instead, they’re interested in castles and knights. There were the remnants of a castle, at least that’s what a plaque said when you stood on top of what was a rather measly hill — both in terms of height and width. But it was said hill that constituted the remnants. The castle, said to have been occupied by pirates that ravaged the North Sea (see, that was exciting history for a young boy), had been razed to the ground centuries earlier. The first sword I saw in one of the small towns nearby barely looked like one, given it had been extracted from rather wet ground, providing me with a lesson that is still very valid for me today: in general humidity isn’t great if you’re interested in preserving things, whether swords (I don’t own any) or books.

As an adult, you’ll never shake all of what excited you as a child, especially not if you’re eager to keep some of the admittedly naive, yet ultimately creative curiosity that children tend to have. I will admit that even though I have by now seen a lot of different places, I still get most excited when I see something old, a place where there were human beings walking around centuries ago. I suppose that it might sound a little trite to write of a connection with those that came before me. But I think that there is a little bit more to it. That connection would be impossible if those human beings had not lived and worked in a community that enabled them to carry it forward (or not: visiting Pompeii left a deep impression in me). It’s possible that I’m writing these words the way I do because I now live in a country where that connection is shallow. While the small town I currently live in is proud of its community, that community pales in comparison to what I know from Europe. And it’s not necessarily a European thing at all. I know that there is a long tradition of civic community in Japan, the one non-Western society that I know more of.

It was by reading Hidden under the Amstel (subtitled — buckle up: Urban Stories of Amsterdam told through archeological finds from the North/South Line) that drove home the point to what extent I am actually not only interested in but also attached to the ideas of civic community and civic pride. If you wanted to see the book as a companion to XXX Stuff (that I reviewed here) I guess you could. That book is a visual catalog of 15,000 items that were unearthed by archeologists when the city of Amsterdam built a new metro line (such infrastructure is part of maintaining a civic community). As I wrote at the time, it’s a brilliant achievement in every way. Hidden under the Amstel is different, though. Instead of “merely” presenting the various finds in an organized fashion, in this book 31 experts (historians, archeologists, and others) present what 107 types of finds mean: how they speak of the daily life of those who owned them and, by extension, how they speak about the city itself and the country at large.

A large part of the reason why this is so fascinating is because for many of the items in question, we don’t actually know all the details. As it turns out, people’s daily lives rapidly fade into obscurity the farther we go back in time. Obviously, written history only remembers famous or important people (where, of course, determining what or who is important forms a large part of the task at hand: that’s where the writing of history becomes political). Everybody else might leave behind no trace other than the items they touched and/or produced during their life time. Hidden under the Amstel dives into this exact aspect of the city’s history: using the 107 types of items, it reveals what they were used for and what the use tells us about life and larger societal circumstances back in the day. Even as my interest in murder mysterious is limited, meaning that I might not be the right person to make the following (trite) observation, I will still make it: in many parts, the book reads like a murder mystery, albeit one where people do not lose their lives.

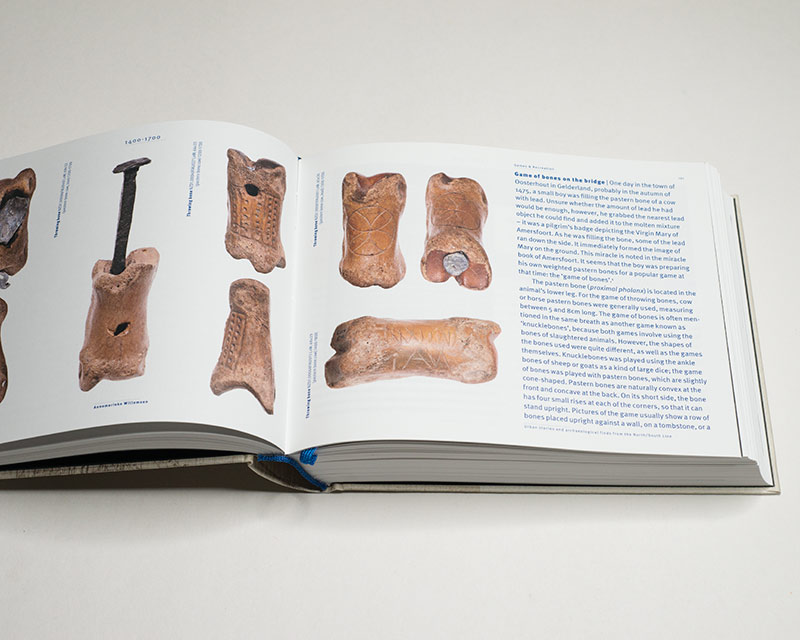

The many authors manage to make the details of the seemingly most mundane items interesting. For example, I now know a lot more about nails than I thought I’d ever be interested in. Furthermore, I had no idea that in the late 1400s, people would play games with little bones that they’d throw. Annemarieke Willemsen, curator of the Medieval collections at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, connects the objects with historical writing and with illustrations. For example, back in the day, it was decreed that children weren’t allowed to play with the weighted bones near a church because of the noise and the possible damage to church windows. For most of the items in the book, it’s stories like these that have them come alive again. I’m imaging the sound of animal bones weighted with lead on a cobbled city street, intermingled with the cries and laughter of the children playing with them.

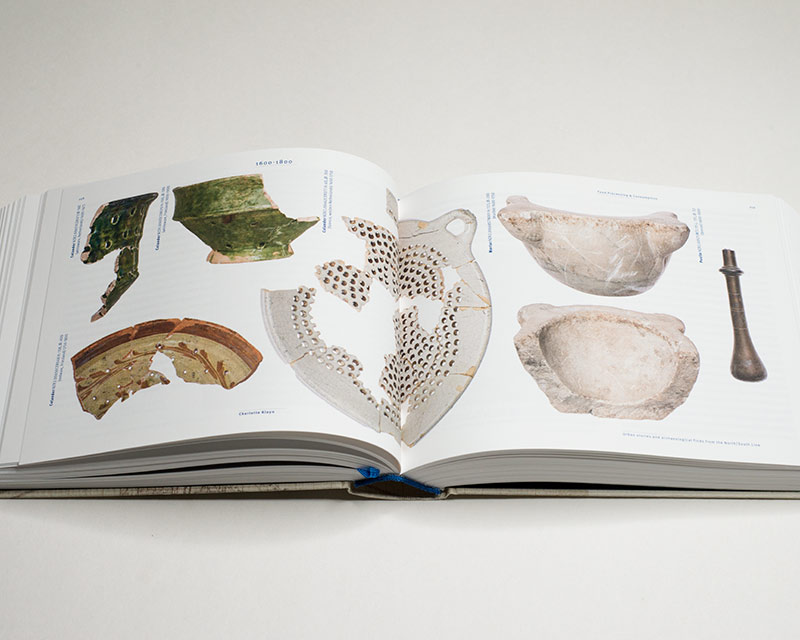

As was the case for XXX Stuff, Hidden under the Amstel was in part conceptualized and then produced by Willem van Zoetendaal. The book is an incredibly beautiful production of modest size but with over 500 pages, filled to the brim with some of the photographs from the older catalogue, with the texts, and with other illustrations from the history of Amsterdam: paintings, etchings, photographs… Reading the book feels a little bit like entering the city’s Wunderkammer, with a trusted expert telling you everything they know about any of the objects on display. It’s not necessarily a photobook in the strictest sense, but then what is a photobook anyway? Why be so insistent on some particular format? It’s true, the photographs play a supporting role here; but without the photographs of these objects (details of which are frequently referred to in the texts) the book wouldn’t work.

Highly recommended.

Hidden under the Amstel; photographs of archeological finds by Harold Strak, with numerous other images and photographs from a variety of sources; 31 authors, ed. J. Gawronski; 2023; Van Zoetendaal

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!