On April 30th, 2019 (which at the time of this writing is tomorrow), Japan’s Emperor Akihito will abdicate, leaving the thrown to his son, Crown Prince Naruhito. It is, so I am told, a momentous event, given that Japanese Emperors don’t tend to do that. Much like British monarchs, they die in office. But the event is maybe more interesting not because of basic facts but because of its symbolism. A new era will begin. Heisei will end, Reiwa will begin.

However, on the last day of Heisei, the country will more of less look exactly the same as on the first day of Reiwa. Political and cultural symbolism tend to be entirely at odds with most people’s lived reality. That reality stubbornly refuses to conform to the expectations placed upon it by the symbolism (if you don’t believe me, just wait for the day when you turn, let’s say, 50): everything changes, we think, and everything just stays the same.

It is this basic fact that has put Japan on a curious trajectory over the past few decades. While the current prime minister seems to want to turn the country into a much more militarily aggressive version of itself, its rapidly aging population is due to increasingly pose considerable problems. This is, of course, a situation not unfamiliar to many other so-called developed nations (including, of course, my native Germany). How to go about this basic conundrum in a day and age where neoliberal politics (that hollow out societies rapidly) are considered the highest good is not clear.

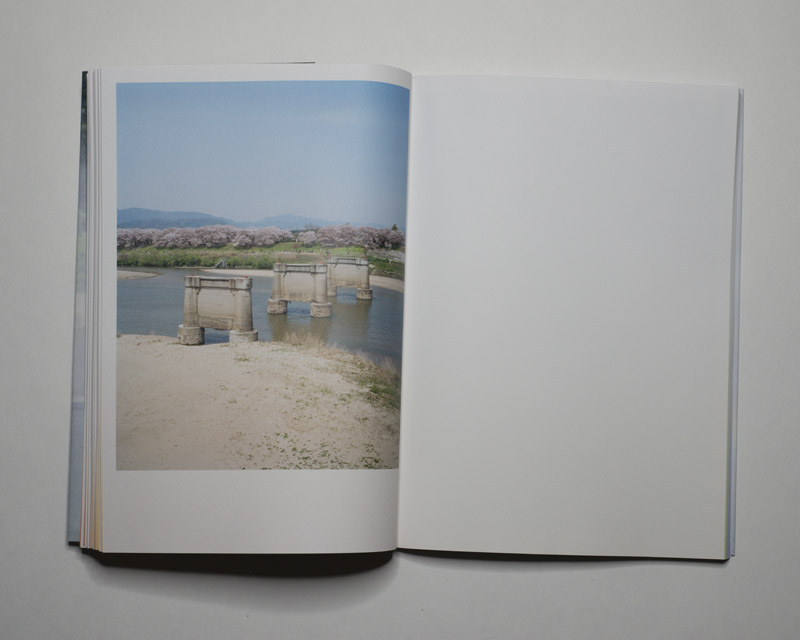

How would one go about dealing with such a situation photographically when all there is to be recorded are surfaces? I think it’s obvious that the only solution is to plow straight ahead and to work towards the symbolism of the recorded surfaces adding up to everything that is inexpressible in photographs. Contemporary photography is filled with work that does just that.

There is a challenge for the viewer, though: these days, I’m sensing the general expectation that photographs, whether as singles or as groups, express more than they actually can. Frustration is expressed concerning a perceived lack of specificity, of photobooks being “too complicated.” As a consequence, many photographers are embracing what I call art-editorial photography: photographs that look like they were made to illustrate an article in some magazine (we just saw the release of a very prominent example). There is nothing wrong with such work even though for me it falls way short of the medium’s true potential.

The alternative route is to let photographs do their job, realizing that what they will add up to is ultimately left to the viewer. This approach was pursued by Miki Soejima in The Passenger’s Present. I always tell students that one should make photographs or books for a sufficiently attentive audience, an audience, in other words, that will spend some time with the work without wanting to be presented with immediate satisfaction (for that they’ll always have the art-editorial work). This book could serve as a good example of what can happen when one does indeed spend some time.

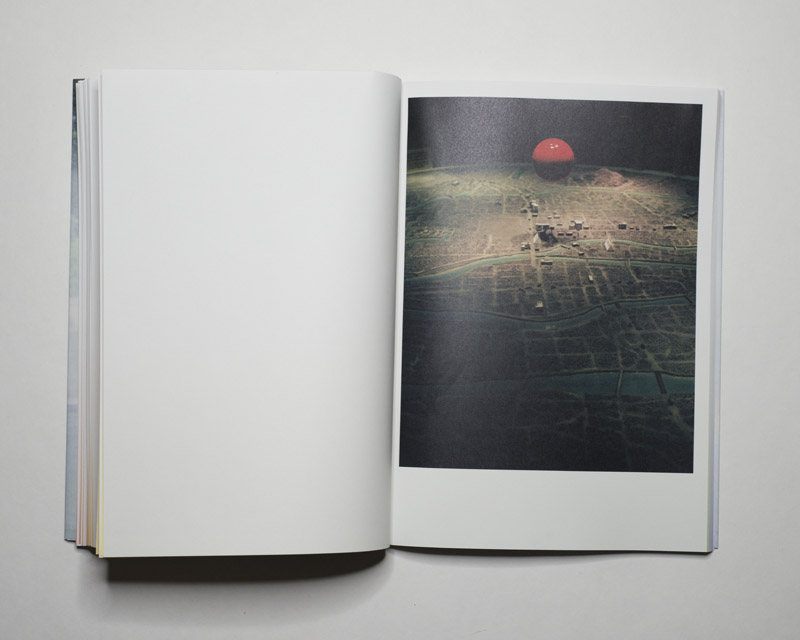

Just to give one example, the second photograph in the book shows two red spheres in a rather minimal still life. Anyone not living under a rock might connect these red spheres with the flag of Japan, in which the red circle represents the sun. There are, of course, no two suns. But a few images later, there is another such red sphere hovering curiously over what looks like a diorama of a destroyed city. There probably is no need to spell out what this means. The very last photograph in the book then shows a cluster of very bright red flowers against an otherwise somewhat dreary background, setting what could be seen as a counterpoint to the other two images.

There is a lot more symbolism being used throughout the book, some of it in straight photographs, some in constructed still lifes. What this all adds up to in the end is not all that clear — but I think that’s exactly the point. After all, if it were a photographer’s task to provide solutions (or, possibly, solace) then she might as well put down the camera and become a politician (or therapist).

So what Soejima does with the book is to express her conflicted feelings about Japan — at least that’s how I see this. And that’s more than enough for me. After all, it’s now up to me as a viewer to imagine myself in that situation, or to maybe think back to my first trip to the country to think about what I possibly sensed, or to think about my own native country to consider my own misgivings about it.

Much like many contemporary photobooks The Passenger’s Present thus presents a riddle, and the viewer’s enjoyment derives from being presented with that riddle — and not its solution.

The Passenger’s Present; photographs by Miki Soejima; 128 (pouch) pages; Fw:Books; 2018

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.4

Ratings explained here.