Sometimes, I wonder why I’m supposed to meddle in the lives of strangers. OK, I understand that I’m not really meddling when I’m looking at an art book in which a total stranger exposes their own private life. Still, it does feel like meddling. Or rather, it’s not the looking that feels like meddling, it’s the writing about it.

More often than not I’m thinking that the only people who really care about these photobook reviews are the books’ makers — the photographers, the publishers. I’m not really meddling, then, more like writing an extended set of words from which they can pick a blurb for the websites (if, that is, I’m complimentary enough).

I also know that when photographers ask you “what do you think?” after they’ve shown you their pictures, they’re not really asking for what I am in fact thinking. Instead, they want reassurance more than praise. Praise is cheap and can be had accordingly. Reassurance, though, is hard to come by in this cold, neoliberal world.

Sometimes, I wonder how or why I ended up in this position as a person who is supposed to provide that — reassurance, especially if the work in question is very personal.

I suppose especially with very personal work that’s the biggest challenge: to publish very personal work that will be meaningful in the fullest sense only to yourself.

Then again, we could probably say that about any piece of art made. Who other than the maker will see everything that went into it?

But that’s precisely where art will be art, namely in all of those infinite situations in which a complete stranger sees something in what you’ve made that resonates deeply, even if the people in the pictures are complete strangers.

Obviously, there’s also the sisterhood or brotherhood aspect of art, in which a group of people, whoever they might be, can relate because theirs were the exact same experiences even if their pictures or words would have been completely different.

Which leads to the very valid question of how you would even assess the “success” of a photobook (or any piece of art) other than by insisting that it succeeds on its own terms?

But that can’t be quite it, because it sounds so detached, especially in cases where a book centers on the possibly the most personal experiences a person can have — a mother dying, two young daughters coming into this world.

If the emotions come across that’s everything you can ask for. Everything else is a bonus. What does it matter what a total stranger, sitting far away in his own home, has to say about it?

I suppose if I had been involved in the making of Lydia Goldblatt‘s Fugue… Which already is a ridiculous way to talk about the book, given that I have not been involved. Still, if I had been involved I would have pushed for the book to be simpler, because its underlying emotions are simple.

It’s the simplest emotions, though, that are hardest to deal with. Grief is such a simple emotion, and yet it can be so overwhelming. Love is simple as well, at least in its most basic form.

What makes emotions not simple is the fact that we’re not well equipped to allow ourselves to exist in their simplicity. We tend to make things too complicated, or we are being pulled by conflicting emotions into different directions, or those around us are so concerned about us that things will become much too complicated, because everybody is trying too hard to avoid hurting feelings where there are so many raw emotions already.

I don’t have any children, so I have no way of knowing what that feels like. It’s mostly second-hand knowledge — and not actual experience — that’s driving this writing.

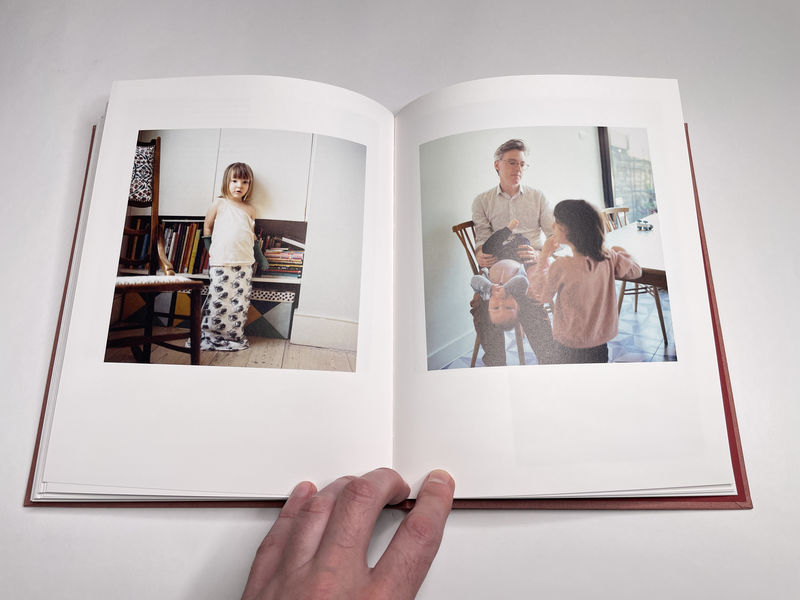

In my life, I have experienced being pulled into different directions. But I have not experienced it in the context of a parent dying while there are young children in the house. And it’s not just a parent dying in the book, it’s the photographer’s mother, and it’s not just children in the house, it’s her young daughters.

I’m imagining that under these circumstances, beyond the grief and the love there is another emotion that here and there comes across in some of the writing in the text. Or maybe I’m imagining it. And I don’t even know how to put it into words in a fashion that will get at what I think might have been present (because ultimately, only the photographer will know).

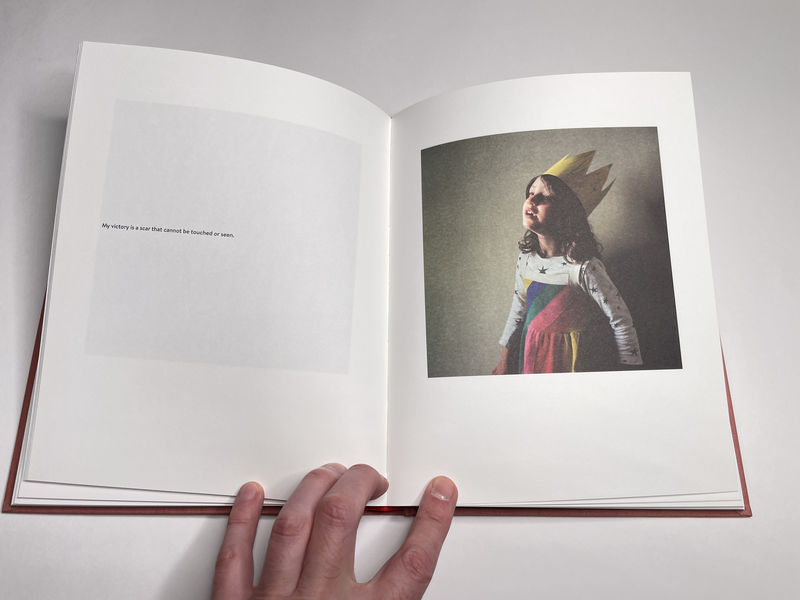

But there is this chain of women that’s continuing through the generations, and every woman in that chain is merely a link, a link that, yes, is incredibly important, but that is also being used by those coming after her.

This connects to what many women have told me about being mothers and trying to be something else (a photographer, an artist, …) at the same time. Usually, you can only fill one of those roles. So there’s a decision to be made: in any given moment, do you want to be a mother or do you want to be a photographer?

Having a moment with one of the daughters, Goldblatt describes this basic conundrum: “Turning to the window, I meet our reflection in the glass […] I like seeing us together, the embrace…” But then comes this: “I think that I should photograph it, but it’s too dark, and I don’t want to exchange child for tripod, the embrace giving me as much as it does her.”

The embrace giving her as much as it does the child — except for a picture: “An unmade image to add to the archive.”

There it is, one of the many complications that sits on top of the simple emotions. I’m imagining the wrestling in the photographer’s head (even though obviously I have no way of knowing): should I do the picture or be in this moment and enjoy what it gives me?

Assuming that there was even that choice. After all, especially with very young children, there is too much work to do, while there is only so much time left, only so much mental energy left. How would you explain this to your photographer colleagues that you’re a photographer but you are unable to take pictures? Maybe ask them to read, say, Rebecca Solnit’s writing about it?

So much pulling from so many directions.

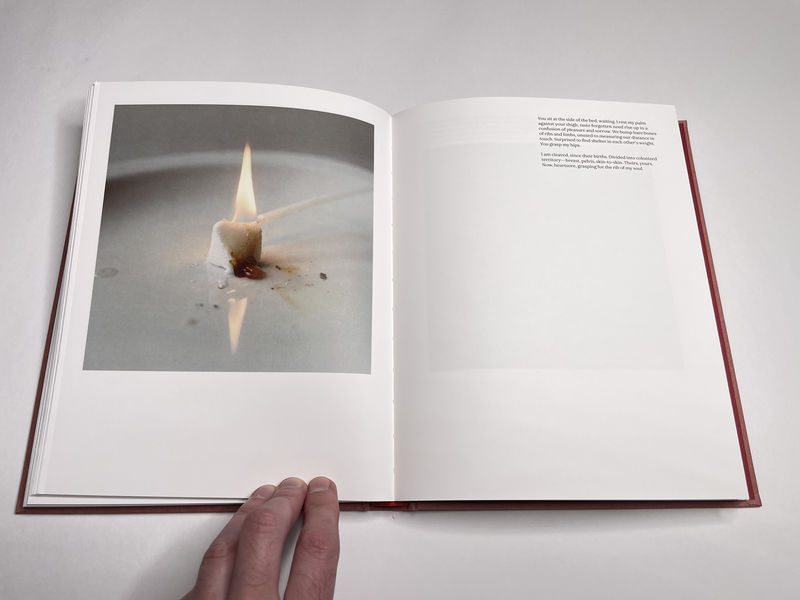

As I already noted, there are photographs in the book alongside Goldblatt’s own writing. It’s the writing that mostly pulls out the mother’s death and its aftermath. And a reader will have to pay attention because the writing will not reveal things too easily.

Once again, I’m thinking that this should have been simpler. But life itself isn’t simple, and dealing with simple emotions isn’t simple. After all, as someone who comes to the book, I’m hoping to connect to my own emotions by way of a stranger’s. In the end, though, it’s not my own mother that has died, it’s this stranger’s.

How could I possibly ask for this to be told more forcefully when I possibly couldn’t do the same — were the roles reversed?

Because that’s the thing, we always ask too much of artists. We always want them to be better and more perfect people than we are. We want them to be making all the right and perfect choices, simply because we are incapable of doing that in our own lives.

There are those pictures in the book where the two conflicting strands I spoke about come together. Maybe the light was right, maybe there was no tripod to be produced — it doesn’t really matter.

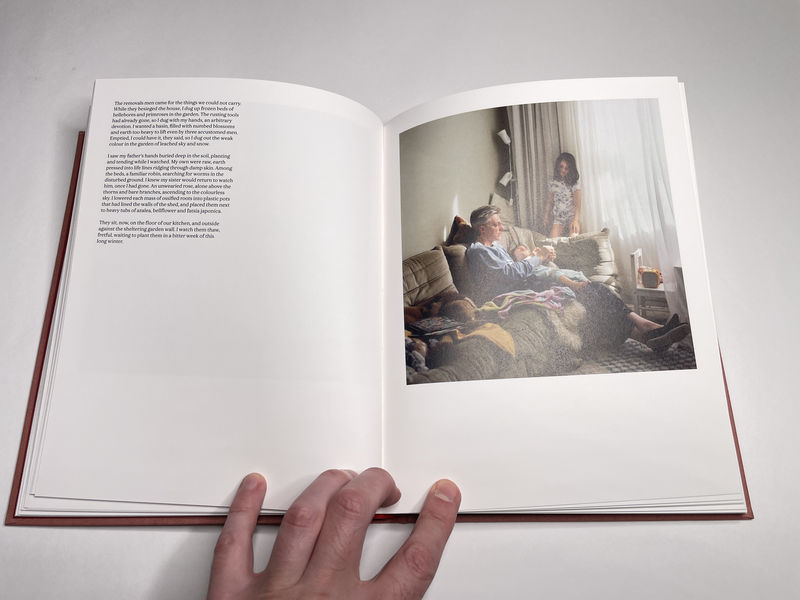

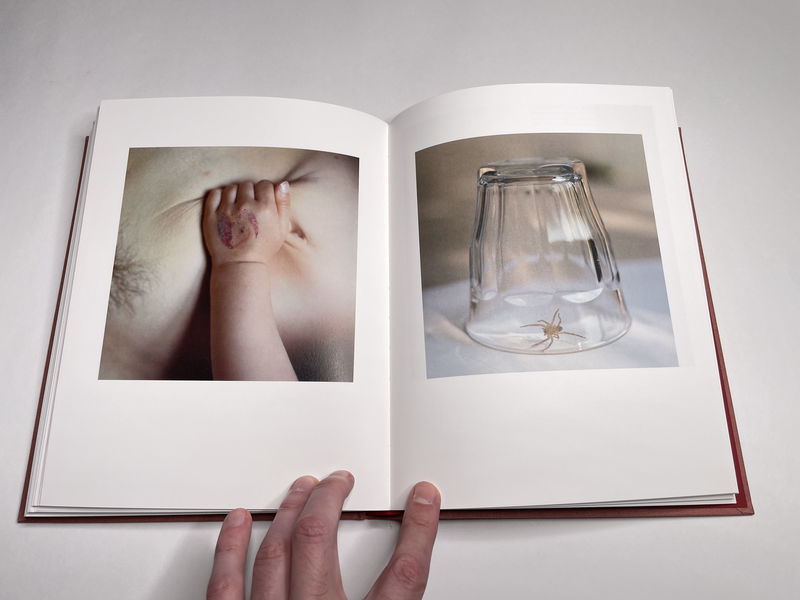

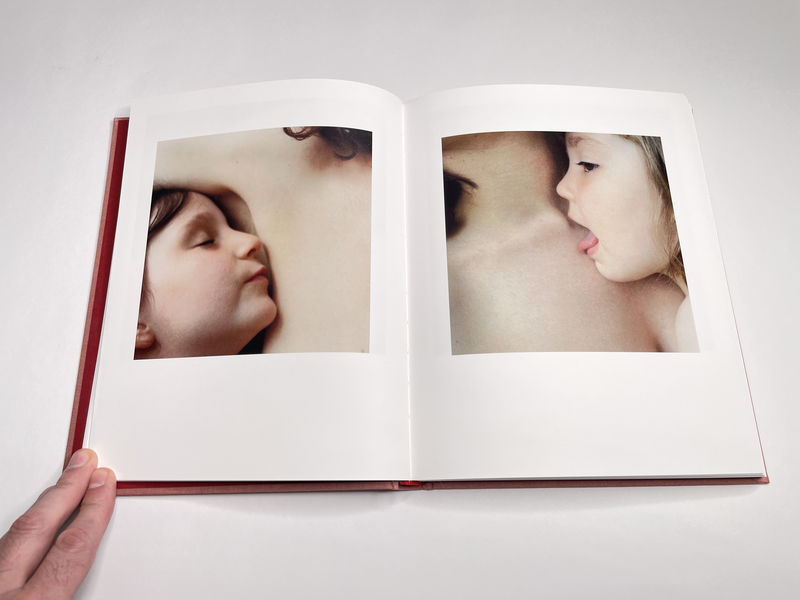

For example, early on in the book, there’s a spread that shows two photographs of the daughters nestled against their mother’s body. The tight framing forcefully pushes their girls to the fore.

In the picture on the left, the daughter’s eyes are closed as she lies in her mother’s armpit. In the picture on the right, the other daughter appears to be licking her mother’s collarbone. Through the layout, the two girls are made to face each other, and in the center, in their center, there is their mother, the photographer.

Even as what we see of her merely is some skin and a few locks of her hair, she is the complete opposite of what is on view in those invisible-mother photographs that routinely make the rounds in photoland. She’s very much the visible mother. She is the center of their world. There is incredible tenderness in this spread, and so much love.

Through the hectic edit and the desire to include too many pictures, some of that tenderness and love gets lost a little bit. And obviously, it’s not just those emotions, because there also is the grief, and there are all those other emotions.

But for me, the book succeeds the most in those moments where a picture, however reduced it might be, reveals the whole world and where a picture (or two) is (are) given the chance to do that.

There is no shortage of photobooks about children made by photographer mothers. In fact, there is no shortage of photobooks about family. For the most part, I have never been particularly interested in them. It has taken me a long time to understand why: in almost all of the cases, the mother (or father) made the decision to be a photographer first and then (maybe) a mother (or father).

I mean that’s fine, who am I to tell people what to do? If you want to be a photographer first and then a feeling human being, I have no problem with that.

But I’m not looking at photobooks to see photographs. I look at photobooks to encounter life.

That’s why all those books filled with sticks and stones, made by (mostly) male photographers who have feelings (or think they do), leave me cold. In the end, it’s not the feelings that shine through, it’s their avoidance of dealing with those feelings by taking pictures that you can frame and hang on a wall: it’s just stick and stones.

What makes Fugue so special is that it appears to have arisen from a situation where the opposite happened. It’s a book filled with photographs that are infused with emotions, with being gentle — even where two of the protagonists often enough were not gentle at all (young children tend to explore the full range of feelings and experiences around them).

In the end, the two people for whom this book was made are the daughters. I don’t know whether the photographer feels that way. I’m just going to make the claim anyway. I have the feeling that once they’re old enough to be able to see and understand, they will treasure the book forever.

For the rest of us… We can only partake in small parts of what they will see — and connect those small parts with the larger emotions in ourselves. It’s very much worth it.

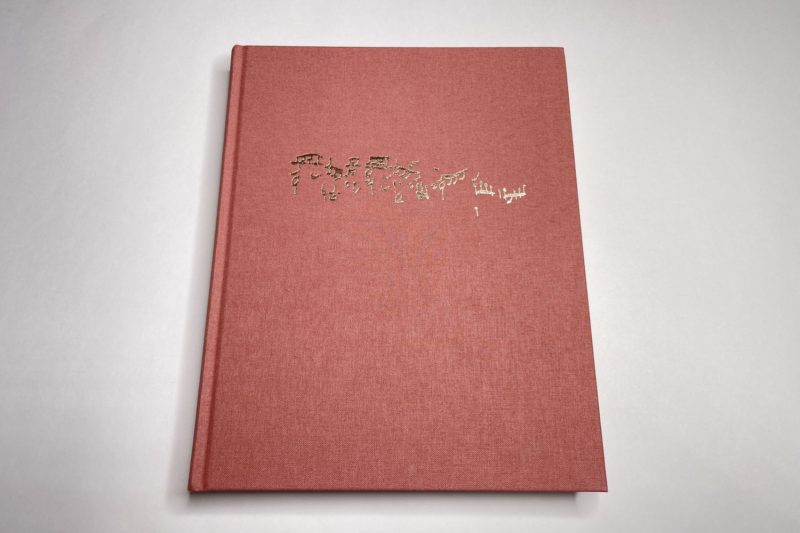

Fugue; photographs and writing by Lydia Goldblatt; 192 pages; GOST; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!