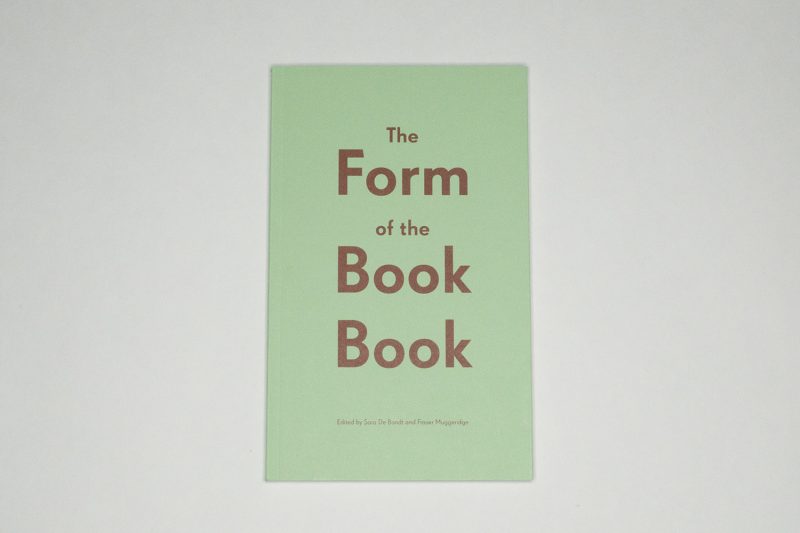

Of all the books in my library, the one with seemingly the most intriguing title is The Form of the Book Book. A look inside will make it very clear how and why there is absolutely nothing peculiar about the title at all: a number of essays by well-known designers explores the form and function of books working with photographs. Yet somehow, its mint-green cover also has it stand out among the other books around it as well, making me look at the spine regularly. Ah, yes, the form of the book. It’s a useful reminder that it matters, that, in other words, as a photobook maker, you will want to consider the overal form of your book, in other words the design along with the choices of materials.

Given there are so many Tupperware photobooks — books where the photographs were dumped into a generic looking and feeling container, I find well-considered books rewarding. Especially in the US, there is strong resistance to producing anything other than a glorified Tupperware photobook: after all, shouldn’t a photobook be concerned with the pictures?

This attitude is grounded as much in the fact that the world of US photography is overall very conservative (for many practitioners, contemporary photography means the likes of Garry Winogrand), that the role of design and production usually is not very well understood at all, and that many photographers don’t trust in the power of their pictures. After all, if you know you have good pictures, you’re unlikely to be worried that design might somehow overshadow them, right?

So let’s look at a number of recent photobooks using this particular angle.

When I received Stijn van der Linden’s Essay on the Concave City Corner in the mail, I was bewildered. The mailman made me sign for a very long package, and I didn’t remember having ordered anything long. Having received a great many photobooks in the mail, I knew their boxes or envelopes would typically be wide, tall, and more or less flat (as an aside: if you ever publish a photobook, do yourself a favour and never send it in merely an envelope). But no, it was a book that clearly required the unusual dimensions of its packaging (it’s 13 x 36.5 cm). There was, however, no information on the cover or spine — other than cryptic numbers (if you ever publish a photobook, do yourself a favour and print the title and your name somewhere on the cover and spine).

Looking inside, I found photographs of a large number of corners in some city that each come with a little diagram plus some more cryptic numbers underneath, making it the kind of conceptual photobook that does not need to rely on anything other than competent pictures. The former scientist in me found that potentially interesting, and the few science corners in my brain that are still in operation started attempting to figure out the meaning behind all of it. At times, there are gatefolds in the book that are constructed in such a fashion that parts of separate corners will combine to form a new one until the viewer unfolds the paper. Neat.

After the sections containing the photographs, there is a lengthy essay about the project, which I have to admit I never finished reading. I tried a couple of times, but it’s just too tedious (that’s obviously on me, not on the writer). I did, however, read the end (this writer knows some of the tricks), to arrive at “this research on concave city corners might be criticized for failing to answer a meaningful question. This could be extended to a critique of the scientific process as a whole, nowadays above all incentivising scientists and academics to publish or perish” (with a footnote pointing to some article on VOX). Hmmm, OK, this is cute, but this former scientist would be tempted to think that — as you say in German — der Schuß geht nach hinten los (which in English rather prosaically means it backfires).

After all, if anything I’d see the book as one of those many attempts by an artist to mimic the scientific approach (honestly, how many projects are there where some photographer is “exploring” something?); to then take the whole thing, to apply it to the sciences, and to say “hey, look, I’m just going to show you how meaningless so much of science is” — that doesn’t quite cut it for me.

In fact, it’s the criticism approach that bothers me. Had this all been done in a completely deadpan fashion, as, in other words, an attempt to come to conclusions about cities based on their corners, then I would have been happy. There could be, after all, a scientist engaged in what to laypeople might be similarly meaningless research.

Especially in this day and age where, to give the possibly most important example, a tiny minority of freak scientists and pseudoscientists is used by the fossile-fuel industry and right-wing governments all over the world to question climate science — in such a day and age, this questioning of the scientific method and its process contributes to undermining the very sciences we need to take more — and not less — seriously.

That aside, ignoring the fact that the book makes it so hard to find the name of its author and title (there’s no title page, either), the form of the book is about as good as it gets. It employs all the right tools and tricks to present its information, and it literally stands out. It is a book that you will remember (even though you might never find it in your library again, given there’s no information on its spine).

Essay on the Concave City Corner; photographs by Stijn van der Linden; essay by Stijn van der Linden and Katrien Vanherck; 144 pages; photobook week arhus; 2019

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 3.8

As far as I can tell, there’s no shortage of photobooks about guys who decide to build and/or live in cabins in the woods. A future critical history of photography should contain a little chapter about this particular topic (which, I’d argue, is tied to many photographer’s focus on depicting the lives of underprivileged bearded strangers living off the grid or roaming the lands). How refreshing then to find the following in the larger text piece of Karianne Bueno‘s Doug’s Cabin: “I shoot a full film on the graveyard and car wreck, despite knowing they’ll be too cliché to use. Regardless: I feel great. Like a conqueror. I, the city dweller, found a hidden piece of history in this faraway fairy-tale forest.”

Much like all books I’ve seen by Breda based The Eriskay Connection, text plays a vital role in this book. Bueno’s first-person account describes what the photographer saw as much as more general aspects of the process, in particular her being out of place in her chosen location. That, I’d argue, is one good approach to solve the conundrum of some “city dweller” photographing this kind of situation.

In addition to being very smart about the inclusion and use of text, The Eriskay Connection also excel at working with design and materials. Bueno’s photographs of landscapes are often presented full bleed, which especially in the very beginning very aptly sets the tone of the book and which makes for an immersive experience for the viewer. Of course, archival materials are being used, and those are printed on a different paper, on newsprint actually, and those sections are untrimmed at the bottom (with trim marks provided for the viewer).

I was writing “of course” because archival materials appear to be a prerequisite these days for photographers attempting to portray strangers living in the woods. The more often I see this, the less I like it. To be honest, to me the use of archival materials has begun to look and feel like an unnecessary trope (obviously, your mileage might vary). Instead, I would have preferred to see some actual people here: some faces (c.f. my earlier piece You Haven’t Seen Their Faces).

Near the end of her text, Bueno writes “I admire Doug for his way of life. Untamed nature, solitude, and confrontation with one’s own insignificance within the planet’s bigger picture, has always deeply haunted me. I admire his fearlessness.” As much as there is a lot to unpack here, I appreciate the photographer’s honesty. Might she not be describing the sentiments of all those venturing out to photograph, say, bearded strangers in the American West?

I don’t think the honesty absolves the photographer of the possible problems that come with such a portrayal. That future critical history of photography might venture into that (somebody commission me already!). But this is a good first step for larger parts of photoland to examine their motivations for putting certain types of people — more often than not quite a bit worse off — in front of their expensive cameras.

Doug’s Cabin; photographs and text by Karianne Bueno; 180 pages; The Eriskay Connection; 2019

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.4

When you first look at Grid Corrections by Gerco de Ruijter, open the book at page 157, and marvel at the following 143 pages. This, essentially, is visual communication in book form at its best. It’s incredibly elegant and actually somewhat understated. But the combination of very smart design and production choices makes for a thrilling experience for the reader/viewer. Perhaps not surprisingly, the book was designed by famed Irma Boom Office (who is Irma Boom? you might wonder — watch this video to find out).

At the core of the book lies the fact that in order to organize land, grids have been the go-to solution in the post-Enlightenment West. You can see such grids in an abundance of example culled from Google Street View before and after the book’s central section. Looking at these screenshots, I am reminded of modernist ideas of grid-based graphic design. The grid is obvious and easy because it tessellates very well — unlike the irregular, rounded shapes used to organize medieval European cities (or farmers’ plots), say. As is well known from the game Tetris, the grid works best if squares or rectangles are used, ideally all of the same size.

So there’s the idea of the book. That’s it. That’s all you need. Simple ideas are often the best, in part because simple is not the same as simplistic. Still, De Ruijter’s idea could have resulted in a dreadfully boring book, had there not been the smart and elegant design and production. Sometimes, that’s all it takes to elevate a book out of the pit of boredom (that all those Tupperware books exist in).

Now, I can imagine the Tupperware crowd to argue that the pictures aren’t that interesting, and they’re right. They’re not. But that’s just missing the overall point here. This is a not a book filled with jewel-like pictures. Instead, it’s a photobook that conveys an idea very well and that makes for an incredibly engaging experience. And there really is no need for any more description or commentary other than if you have the chance at all, you certainly want to look at this book to see what can be done with smart design and production choices.

Grid Corrections; images by Gerco de Ruijter; text by Peter Delpeut; 304 pages; Nai010 Publishers; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.