We don’t really know much about Tomas, other than what we can infer from the photographs and words he left behind. Oh, and there are the snippets of memories by his grandson Terje (Terje Abusdal, the photographer), who was too young to ask more questions around the time Tomas took his pictures.

Tomas moved in with Terje’s family after his wife had died. He was already in his seventies. Even as his upcoming exploits — in the form of travels — would hint at a man aware of a newly found freedom, it would appear that he also was fundamentally lazy. Without a wife serving him life might have been too difficult, too tedious certainly.

There’s a short story in Costa Bravo Holiday Paradise about how Tomas, the widower, went to see his childhood sweetheart who had remained unmarried. Alas, he was told that now it would be too late to get married.

Which is interesting, because on the one hand, there is the possibility of romantic love and the reality of life near its end. On the other hand, the childhood sweetheart might not have needed a possibly rather helpless and lazy old man to take care of, given she had avoided just that all her life.

We will never know. We can only imagine.

By the way, if you spotted a typo in the title: congratulations! It’s Tomas’, and Terje carried it forward. So please don’t email Terje or me. We know.

But it’s a very interesting typo, isn’t it? Having taken up traveling late in life, Tomas went to a number of places to enjoy the good life. This included the Costa Brava. I’m imagining that he maybe misread the name of the locale as a confirmation that finally!, he had taken up living the good life. Bravo! (Again, we will never know.)

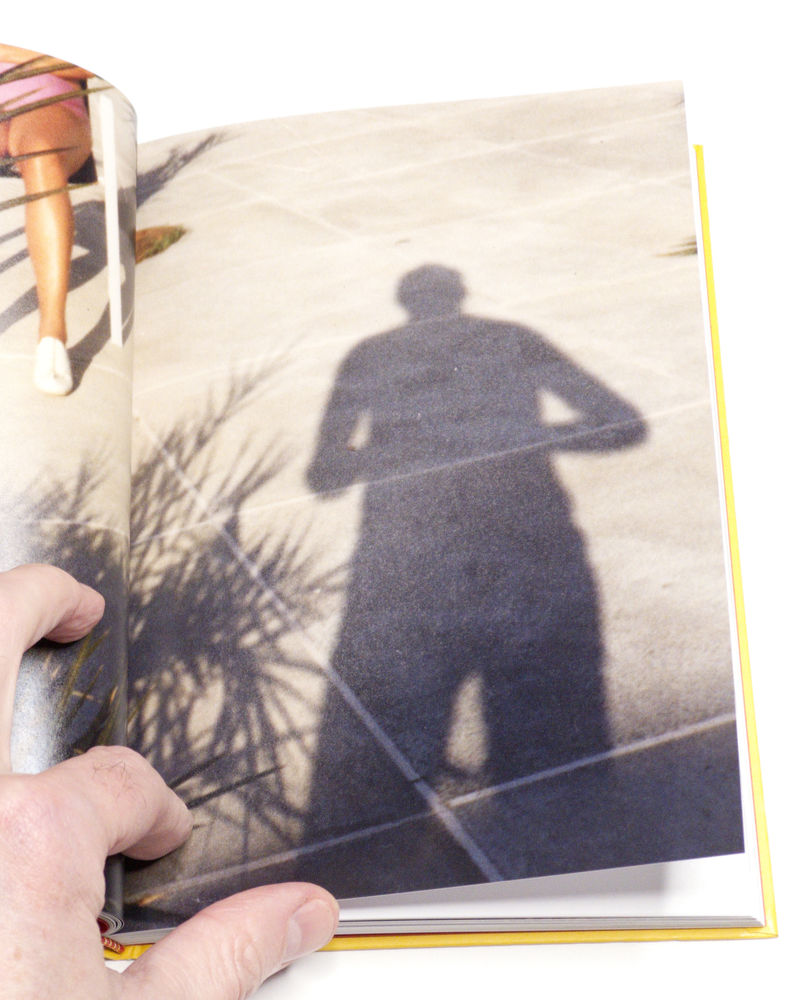

The good life thus consisted of traveling and seeing places and people. People inevitably included women, and as far as one can tell the seeing remained that, seeing. “There are many out of focus pictures of younger women,” Terje writes, “and over seventy self-portraits. He gave the camera to strangers and posed.”

For many of his photographs, Tomas wrote short captions. The photographs are interesting because they’re so utilitarian and artless, and the same is true for the captions. A somewhat blurry photograph of some red and white flowering bushes, possibly located in the setting of a shopping mall, comes with the caption “Many flowers” (the captions were all written in Norwegian, there are English translations underneath).

It’s hard to tell whether there was any depth to Tomas’ life. There might not have been. Depth does not necessarily make for an interesting or good life. (The lack thereof doesn’t either, though.)

At some stage, Tomas was so old that he was unable to travel on his own any longer. Given the above, you can probably guess what happened. Yes, that’s right, family members had to travel along to make sure that Tomas was not missing out.

And who can blame him? From what Terje infers, Tomas had never liked the work he had had to do his whole life. And he might not have liked his deceased wife, either: “There are no pictures of his wife in the albums. There is only an image of the headstone on her grave.”

Ultimately, though, all we can do as viewers is to infer what we might be able to come up with, given the photographs and the few details that Terje is able to remember or was told earlier.

The more often I look at the book, the bleaker it gets. Obviously, that’s me seeing Tomas, and it’s me seeing the world. Your own impressions might be very different.

There have been many books made with photographs left behind by often nameless strangers. Working with such imagery has spawned its own industry, with some artists doing only that. The problem with those books for me usually is that the material is enticing or maybe even really interesting. But once the novelty has worn off, you’re left with… Well, not much.

In the case of Costa Bravo Holiday Paradise it’s the other way around. The photographs aren’t particularly spectacular. But there is enough in them that forms an image of the person who took them (or had others take them for — and of — him). There are, in other words, many small hooks that attach to a viewer’s own flesh, making her or him think about life choices and about what it means to be a person in this world.

Whether or not the life choices one infers for Tomas have anything to do with reality is completely besides the point. The man has been dead for a long time, so there is no way of finding out. It seems clear, though, that he managed to set up a relatively happy ending for an otherwise unhappy or maybe discontented life.

And that’s what we all have to do with our own lives: deal with their realities and see what we can make out of them. Ideally, we’ll be starting to think about this a lot earlier than Tomas might have done.

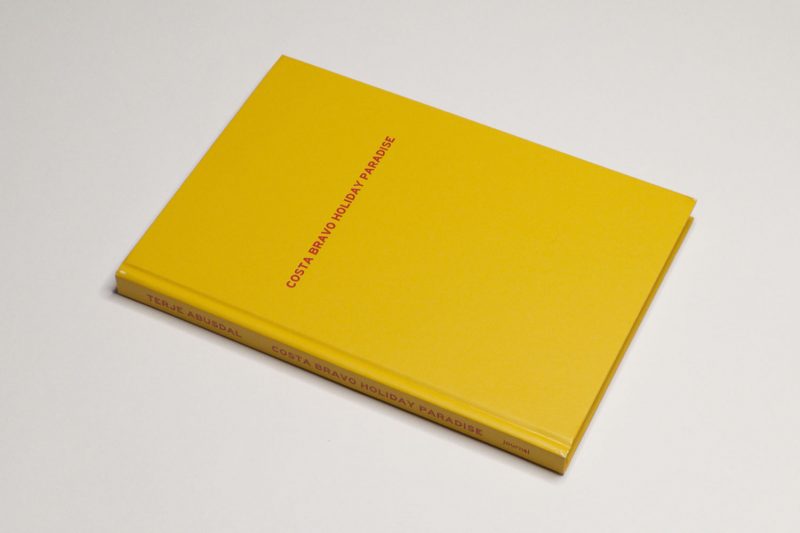

Costa Bravo Holiday Paradise; photographs by Tomas Mølland, edited by Terje Abusdal; 144 pages; journal; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!