Earlier this year, I spoke with my friend Tobias Kruse about Deponie, a body of work that he photographed in East Germany. At the time, it was only available as a newsprint publication. But now, Tobias has made a new version with Spector Books, and the photographs are going to be on view in Berlin from mid December this year until the end of January 2023. This seems like a good moment to share the conversation I had with him.

Actually, it was maybe the most unusual interview I’ve ever done. I asked an introductory question, and Tobias told me the whole story, without me having to ask any further questions. The following is a transcript of Tobias’ words, edited for length and clarity and translated from the original German.

I had wanted to work on the project for a while, maybe for ten years. Then in 2015 the so-called refugee crisis and Pegida and the AfD happened. All of a sudden I had the feeling “Shit, you’re familiar with this. This happened before. You wouldn’t be able to go to a restaurant in the countryside without getting harassed from all sides. You know what it’s like to feel unsafe everywhere.“ There was this feeling of „I don’t belong here“, a feeling of „this is dangerous“. Everything could be dangerous. It could be dangerous to go shopping. Somehow the situation had come back, where these people, these radical people, were no longer in hiding but instead showed themselves and their mindsets.

One day, Ingo Taubhorn called and told me that I had received the Olympus Recommended Stipend. That’s what it was called. Unfortunately, Olympus was sold, which ended the relatively short period when this stipend existed. There were only two rounds. Anyway, that gave me an OK amount of money and some Olympus camera gear. I had to use the camera, that was part of the deal. That made it a little bit difficult for me, because I’m not good with new gear. Actually, I simply don’t care about camera gear. When I have a camera that works for me I’m happy.

The grant provided the perfect opportunity to work on the project. But how do I explain what I wanted to do? I didn’t really know I wanted to take pictures of. But I knew the feeling associated with the project very well. It’s a feeling of anxiety, of something unpleasant, associated with the concept of Heimat. The focus is indeed that I am from the East. But it doesn’t only center on the 1990s.

Something has emerged (already at the time of the fall of communism) that was kept under wraps for a long time. It’s the fact that there were and still are very widespread authoritarian attitudes in the East. After the end of Nazi dictatorship those continued during the SED dictatorship. It was as if those attitudes were immersed in nutrients. They held up quite well. And that has continued until today. There is the relatively well-known study done by a Leipzig centre studying authoritarianism, which is being conducted every two years. It uses relatively subtle questions to ask Germans how they feel about certain things. Results have consistently shown that the trust in authority is actually much higher in the East than in the West. Researchers produce statements such as „What Germany needs right now is a single, strong party that embodies the people as a whole.“ And 38% of people agree with that. That’s crazy, isn’t it?

The 90s were totally intense. I was 10 when the Wall came down and 11 when reunification happened. At the beginning of the 90s, there were Nazis everywhere in the East. You’d go outside and ask yourself “Which way do I walk now? I’d rather not cross Platz der Freiheit“, because that’s where they always met. We always hung out in the youth center. That was a fairly left-wing youth club in Schwerin, the city I grew up in. The center was also attacked by them. At the same time, after the fall of communism there was a deluge of drugs in the East.

For me things were clear: as soon as I’m able to I’m going to go to Berlin. Back then, that was simply the place to be. In addition, party people from the big cities had started to discover the Mecklenburg fields as locations to party. The Fusion Festival was born at that time. Back then, those were events with 300 people. We were there, too. So on the one hand, you had a strong right-wing scene in the East. On the other hand, there also were alternative subcultures in smaller numbers. We were always fewer than them. And what we did wasn’t all good either. Many people took way too many drugs. Friends of mine died. These aspects show up a little bit in the work.

There was also such an intense moment of freedom. You have to remember that we had been locked up, and suddenly we weren’t anymore. I was young, but I perceived everything very clearly. My parents were Bürgerbewegte, they were members of the opposition. For them, everything was great. My father took part in disbanding the Stasi in the Schwerin district. For us, the fall of the Wall was the most important event in our lives. Now we were released into freedom. But we had no money. We were unable to make use of our freedom. That sucked. We found ourselves being told “now you can travel to America“. But who was going to pay for that? You also didn’t have money to buy Coca Cola. You had to shop at Aldi.

During the first few years, people tried to save their money. For years, people saved money. We kids tried to find shortcuts. We wanted to live life to the fullest. But it became clear relatively quickly that throughout the 90s we were second-class citizens. So there’s this component of identity politics. We were looked down upon. We were ridiculed. It simply sucked to be an Ossi. That only ended at the beginning of the oughts. In Berlin it was a little different because East Berlin was considered cool. But you really only were able to say “I’m from Schwerin” in Hamburg or Munich without worrying about it in the noughties. We East Germans have a fine sense for that. If you’re asked at a party where you’re from, you’ll often hear „ah, oh… from the East“.

Coming back to what I mentioned earlier, about that faith in authority and Nazis in the East… In fact, another type of fascination with the Nazi era has been preserved. My grandparents’ generation who had fought in the war — they were treated a bit like heroes. They had been in France, they had seen the world but in connection to the war. That fact was glorified so much. Those had been the good times before the war. In the East, there were many Nazis, people who were born at the end of the 60s or at the beginning of the 70s, who celebrated this. Of course, that erupted when the Wall came down: now we’re somebody again. All the West German neo-Nazi leaders recognized that immediately. They went East and grabbed people: the dissatisfied, the unemployed, the disoriented, kids… That’s still the case today. The AfD’s entire leadership is from the West.

There is a historical component that has always interested me very much. In the East, it was a thing to look for Nazi memorabilia in the woods. After the war, there were no funds. What was left behind from the war was not properly cleared. Perhaps metal was needed, meaning tanks were melted down. But even today, the forests are still full of war materials. The East had been one of the main theatres of war, because the Reich capital had been there. Around Berlin there still are thousands of installations, bunkers, and all the concentration camps: Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald… Buchenwald alone had over 400 subcamps. South of Berlin, East Germany was littered with subcamps. Nobody can tell you that they didn’t know that. They were everywhere. In Nordhausen in the Harz region, it was on the market square. Sachsenhausen is right here in Oranienburg. In Fürstenberg was the Ravensbrück women’s camp. These two concentration camps also had subcamps as far away as the Baltic Sea. In Buchenwald you arrive at this big parking lot, and there are old SS barracks. The Buchenwald staff lived there. Now Weimar squares live in them. The houses belong to the memorial. They rent them out themselves. All this Nazi shit — that was already an issue in the 90s. There are bunkers here that were never cleared out. Of course, Nazis happily have their campfires there.

And there is the landfill, the starting point of the story. If you drive from Schwerin to Lübeck, where back then we went from time to time, you drive past the landfill. (Lübeck was the closest place where you could buy Stüssy tshirts. “Forty marks for a tshirt – are you out of your mind?“) In 1979, they set up a landfill close to the German-German border near Lübeck. The idea was to earn foreign currency. It was done as a hush-hush operation that was illegal under GDR law. Western waste was dumped there for cheap, including from companies such as Shell and Bayersdorf. A lot of waste came from Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein, but also from Holland. It’s a toxic-waste dump, the largest toxic-waste dump in Europe. There was a toxic-waste scandal in Seveso, Italy, in the 80s. Barrels disappeared in Seveso, and it is thought that they’re there. There still are eighteen million tons of toxic waste lying there, and nobody knows what to do with it. The operating permit for the landfill was granted on a questionable basis. It was not really legal, not even under GDR law. In the area, clay and gravel rivers alternate in the subsoil. It is relatively important to know whether it is clay or gravel. If it is gravel, it is bad. Lübeck is not far away, and they are worried that the groundwater will be contaminated. I thought this was quite a nice image for the unresolved issue of Germany’s East and West: toxic waste lying around in the landscape and nobody knows how to deal with it.

You cannot change the fact any longer that after reunification, the entire East was sold to the West. That means that all the real estate is owned by West Germans. It will never get adjusted again. I think 5% of the real estate in East Germany belongs to East Germans. This totally cements the question whether you are an Ossi or Wessi. If you are an Easterner, you inherit nothing. The huge inheritances that are going on right now are all inherited only from West Germans to West Germans. Prices for real estate in the area surrounding Berlin — this surrounding area has become very large, it’s already half of East Germany — are as high as in Berlin. In the Uckermark, 100 kilometers from Berlin, you pay half a million Euros for a simple little farmhouse. Ten years ago it still cost 50 thousand Euros. The people who can buy it are West Germans. Now, West Germans are buying up the very last remnants. It remains to be seen how such a social transformation is going to be handled. You have to make sure that things are fair. In Poland, for example, they put a stop to this development. Twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, foreigners became practically unable to buy real estate in Poland. It was possible, but you had to found a company and that was a considerable effort. But that didn’t happen here. That is another aspect of Deponie.

It was obvious that I wouldn’t do a reportage about a landfill. It’s just a huge green mountain. It’s not interesting. I started taking pictures in the immediate vicinity and realised relatively quickly that that wouldn’t work. So I decided that the project would cover the whole East. I went to places that clearly played a role in my personal life but also for the country: Hoyerswerda, Rostock-Lichtenhagen, and other locations. I drove around a lot. In terms of distance, I covered three times the circumference of the GDR: 8,000km. But initially, I didn’t know what to photograph at all. I didn’t have a list of subjects. I started making a list of words that came to mind while driving. I tried to make sense of them. When you think about a word, you start thinking about images. In the end, I also compiled a list of the places I’d been to. Combined, this resulted in the list that is part of the exhibition.

Images then fell into place. You can also push your luck when you go to AfD events or demonstrations. There’s a legal element to it, because you’re not allowed to photograph people without their consent. But you are allowed to do so at demonstrations and political events.

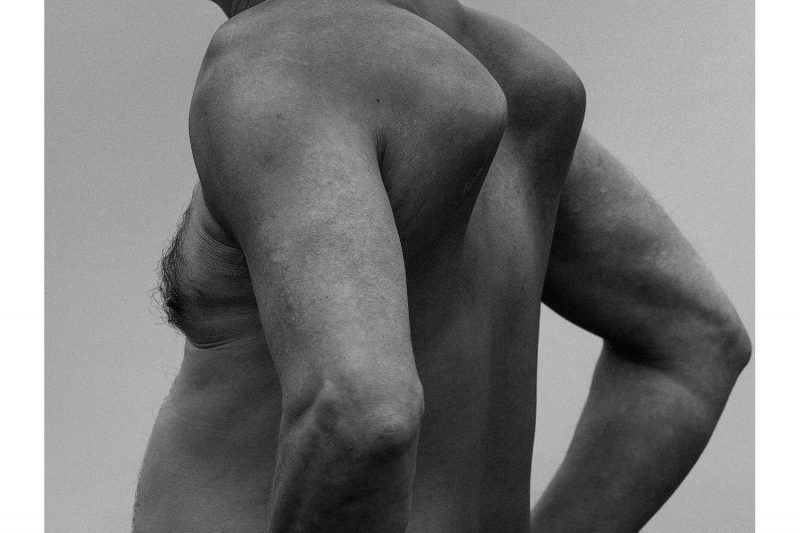

Violence was a topic. Where do you get a picture of a people’s brutalization? I don’t necessarily mean a brawl. Where does brutalization manifest itself? I simply went to a football match: Dynamo Dresden playing FC Sankt Pauli in Dresden. I got accredited and stood at the sidelines. I always stood with my back to the pitch in front of this wall of 5,000 hooligans from Dresden. Whenever the La Ola wave came around, they always performed the Hitler salute. I had not expected that they would show it so openly. I wanted that picture. I wanted to tell the story of the past and present at the same time. That was important for me. That’s why early on, it was obvious that I had to photograph in black and white to create that connection.