Before I met Rafał Milach for the first time in person two years ago, I had known of him as a prolific photobook maker and one of the driving forces behind the Polish Sputnik photography collective. When I went to Warsaw for the first time last year, the US election campaign was still in full swing. Much like many other people I was convinced there was no way someone like Donald Trump actually had a chance to win — I told Rafał that such a blatantly racist and sexist person would simply not get the majority of voters. Turns out he didn’t, but he won anyway — just as Rafał predicted.

At the time, Poland was already under the rule of the authoritarian PiS party, which would bring to Poland what the US has so far been mostly spared, given Trump’s sheer incompetence: an erosion of civil liberties and of democracy in general. With Rafał’s (and Sputnik’s) work centering on the post-Soviet landscape in Eastern Europe, including the kind of politics that now broke out into the open, these types of topics have always played some role for him. We had lots of discussions about it all.

Talking with Rafał about his work for this site had long been overdue. I wish larger circumstances would be a bit better. But if there’s something said about “interesting times,” it is that they can make for interesting work.

Jörg Colberg: To start off, could you talk a little bit about your background as a photographer? How did you come to photography? Why photography and not, say, writing or something else?

Rafał Milach: Actually, I did try something else. I never planned to become a photographer. My primary education is in graphic design, and I wanted to make posters. Poland has a strong tradition in poster design that was paradoxically developed under the communist regime. Photography came as an obligatory course that I had to pass at the Academy of Fine Arts. Not a romantic start at all, right?

I used to draw and paint a lot. But when I discovered photography (mostly documentary) I fell in love with it and almost stopped doing everything else. I could finally refer to so called “real world” which was not always the case in my previous practices. With photography I learned how to observe. Ironically, most recently I started to question the boundaries of photography concerning some aspects of reality that surrounds us. My attraction to documentary photography is still strong. But I started to look for a relevant visual language that could reflect the problems I want to talk about. Strangely photography which is my primary medium seems to be insufficient. I restarted drawing and doing collages or playing with various archival materials.

JC: You’re part of the Sputnik collective. Could you talk about the ideas behind and mission of the collective?

RM: Sputnik Photos was created as a platform to comment on Eastern Europe. The collective initially started as a group of photographers. But with time we expanded our collaboration to writers, graphic designers, educators, cultural activists, visual artists, curators. The only thing that hasn’t changed is that we still refer to the region where we come from. For more than a decade we’ve been working on stories commenting on the economical, cultural, and political transition of the former East Block countries. We’ve published a dozen or so books (group and monographs) alongside the exhibitions that deal with the post Soviet legacy and other aspects. For a couple of years, we’ve also been running our educational platform (Sputnik Photos Mentoring Programme), and we are very proud of our talented students.

JC: Sputnik have been celebrating their anniversary with a series of books and exhibitions with all kinds of different formats. Somewhat unusual, at least for most collectives I know, was that you decided to mix your photographs, not listing individual names. What are the ideas behind this approach?

RM: We indeed celebrated the 10th anniversary of our collective’s activity by launching the “Lost Territories” project. It’s a complex structure which deconstructs the stories each one of us developed in former Soviet republics for the past eight years. The Lost Territories Archive (LTA) that we created doesn’t care about the authorship behind either single images or the stories. Instead, it focuses on the meaning and contexts behind the pictures. For each reading of the archive we build a different narrative for a book or an exhibition.

Reducing authorship in the field of art is nothing new. But in terms of our practice inside Sputnik it was experimental but also a natural process. On the one hand this gesture was required by the structure of the project. On the other hand it was an ultimate way of merging our pictures while working as a group.

JC: Poland has been ruled by a far-right government for two years now. In many ways, the government foreshadowed the Trump administration, with maybe the only exception that in Poland, the reality-TV aspect and the tweets are maybe missing. What has this meant for you, both as a photographer and, of course, as a citizen?

RM: Is it possible at all to separate one from the other, especially today?

We have our local political folklore here. Some of it also includes tweeting, and frankly I wouldn’t complain if it would be just that. But coming back to my position. Early on, I got interested in politics. Not that I wanted it. And I mean the daily politics – not the long term processes and their impact on society that we can explore and digest slowly. Some years ago as an editorial photographer portraying presidents, prime ministers, and politicians for magazines I had to be aware of the current political situation. Then my focus drifted in a different direction, so I was able forget about it. Two years ago everything changed, and I now have refer to our current political environment again.

JC: And then how does one deal with such a situation? What’s photography’s (or art’s) role when confronted with such a massive challenge to basic democratic institutions?

RM: It’s very simple. It has to react to that. I can’t see any other role for art (photography included) than a commenting one. Art is a tool, and we have to use it. If we use it in an intelligent way it can be powerful.

JC: If I’m correct, you had the photograph to photograph the behind-the-scenes ruler, Jaroslaw Kaczynski for a Newsweek cover. When Nadav Kander photographed Donald Trump the result was oddly — and maybe disconcertingly — non-committal (as was the photographer speaking about it). How did you go about your job?

RM: I had an opinion of this politician, and I hope it was visible in the portrait.

JC: Your newest project — and book — now are a deviation from your earlier work, and they seem to reference the situation in Poland and in some other places. Could you talk about it?

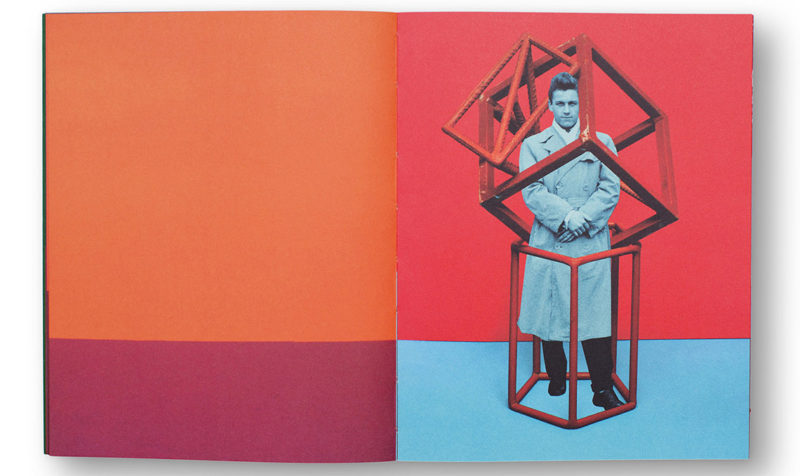

RM: “The First March of Gentlemen” I did within the Kolekcja Wrzesińska residency program is a formally abstract comment on the current situation in Poland. It can easily refer to other places as well. It’s about protest and public manifestations of opinions. It’s my vision of a civic society that in my opinion we don’t have in Poland. We have protested a lot over the past two years in Poland. But it’s still not enough, and most people are simply not interested in politics and in the ongoing processes that devastate democracy. In a way I can understand that: large parts of our society are forgotten and marginalized by people in power, so why would they care?

The series of collages I made is sort of an Arcadian space where citizens express their fears and desires publicly. Regardless of possible consequences they are active.The images contain both the idea of freedom and the oppressive apparatus. The fictional story is based on facts linked to the small Polish town of Września, famous for its children strike against German occupants at the beginning of the 20th Century. A second layer refers to Poland’s communist regime in the 1950’s.