In the world of contemporary photobook making, Laia Abril has become a fixture, having pushed the boundaries of narrative-based storytelling as much as addressing timely and very important topics such as, for example, eating disorders or reproductive rights. Of course, her work is not restricted to the format book. It also is shown at photography festivals and in other exhibition venues. At the occasion of the release of Abril’s latest book, On Abortion, I am thrilled to have had the opportunity to speak with the artist about her background and work.

Jörg Colberg: To begin with, can you give us some background information about yourself and about how you got to photography?

Laia Abril: I studied journalism in Barcelona, and that’s when I came into contact with photography. I guess we can skip that moment when my parents got me a camera – I was 9 years old, and I made a photobook based on my grandmother’s five-house village in the Basque country. Inspired by a teacher who used to be a photojournalist in the Balkans, I made my first trips to that area – although I was still writing at the time. I ended covering some events related to the post-Balkan war.

In class, I was fascinated by the book Non sono obiettivo by Oliviero Toscani, the first COLORS magazines, and the work of Nan Goldin, Donna Ferrato, or Duane Michals. So I started to work as a photographer for the university magazine. After graduating, I went to New York with the intention of enrolling at ICP. There, I began to develop personal projects while attending some courses – see my series Femme Love; still naive as to why those kinds of stories attracted me more than the international and conflict journalism I was suppose to pursue.

It was in the middle of this New York experience that I returned to Europe and moved to Italy since I received a scholarship from FABRICA – Benetton’s artists’ residence and communication center. There, I started to develop my long-term project On Eating Disorders in parallel with working at COLORS magazine as photographer and photo editor for almost five years. It was also there where I met Ramon Pez – former art director of the magazine, starting our creative book-making team.

JC: How would you talk about your general, larger interest as far as your work is concerned

LA: Throughout my projects I focus on telling the most uncomfortable, hidden, stigmatized, and misunderstood stories. I often find myself trying to photograph invisible issues, aspects recurrently connected to mental states, mental illness, prejudices, and taboos. The topics I work on are generally close to my personal experience, since I always thought that it would be easier for me to connect with them and, in turn, be able to translate them for an audience.

Sometimes, I feel my job is actually to get into mental places nobody wants to go to and to digest hard and personal stories, so I can deliver something people would be able to be empathic with and relate to. Indeed, if you ask me about my work methodology, I would say it all started considering the many different approaches to empathy: with my characters and between the work and the public.

It has been said and written about me that I often work on female issues. This might be true, but not all my characters are women, and certainly they are not my only target. But is true that there is a pattern around the politics of difference and human rights. I am connected to topics such as sexuality, ethics, morality, psychology, gender, and identity and how our society handles all these together.

JC: The photobook plays a central role in your practice. Before we talk about individual examples, what is it that the photobook offers for you that has you work with it so much?

LA: I’ve been obsessed with books my entire life. I used to be that kind of kid hungry for getting to the library to devour books and buying them with my family at the flea market every Sunday. I was particularly interested in pure literature, aside from some comic books at my early years. I remember feeling calm being surrounded by books. I still do.

On a more current note, my projects are also research based. My background in journalism allowed me to create a methodology of investigation that precedes my visual documentation in order to achieve a deeper understanding of environments, subjects, and stories. I also grew up with the first generation of modern TV show narratives.

I never understood photography as a “decisive moment” rather than a sequence or a whole. So books allow me to combine photography, text, research, design, and deeper and complex narratives to give the reader time to consume them. Intimate or psychological stories like the ones I do need time to be read, so the reader is able to develop empathy with the subject and finds the mental space to change.

JC: Speaking about projects/books such as The Epilogue or Lobismuller – how do you engage with them? Is there the idea to make a specific book, or do these projects start out with explorations and then end up as books?

LA: I usually work thinking first of the story, then of the platform; then of the tools. I might have been born photographically at that specific time when suddenly we were forced to create content and the platform were the content (images) is going to be consumed and distributed. I could not be happier, since the complexity of the topics – along with my intrinsic urge to always get out of my comfort zone – force me to work across different platforms.

If I believe the story needs to be a book or an installation or a web documentary I will produce it in a completely different way. That doesn’t mean I cannot adapt the project later. But the primary carrier always determines the mood of the content later. Even though I create a story to be shown in, let’s say, a book, later on it can be adapted to be shown in the form of exhibition or something else. But the soul, the mood, the essence of it, is determined by the first platform. This often is a photobook, in the case of On Abortion it’s an installation.

This methodology of work has obviously evolved with time. In the beginning, everything was much more intuitive. Now that also my projects have become more concept based it’s easier for me to visualize the end result in the beginning.

JC: Can you maybe speak a little bit more about the process of making these books? They’re both so interesting, but also so different, so it would be nice to learn a little more about how you made them.

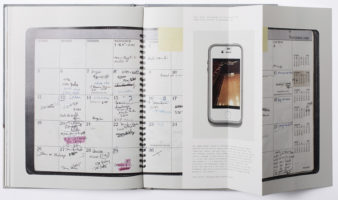

LA: To be honest, it is a very organic process. It has been changing over the years, changing my relationship with photography, with the process of learning, also by changing my relationship with my team and the different stories. With The Epilogue, I produced the story, and when I returned from the trip edit, design, and production merged into one. The visual research process gave us the keys to configure and translate the key elements of the story into an object, the book.

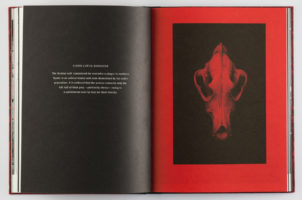

Lobismuller was different. At times, the book had more of the design developed than the story itself because I still needed to photograph pending aspects, and I was stuck. All of these process issues are often also affected by external factors, such as deadlines, creative blocks, production blocks, budgets, etc. As I said for each story, each project, I tend to leave my comfort zone. Lobismuller was my first book based practically on landscape photography, black and white, and analog; I was trying to tell the complex psychology of a character without the character itself being available. The process of editing and design was affected by the search for a solution for the storytelling.

With On Abortion, it was the first time that a project was born as an installation. I photographed strictly thinking about how it was going to be seen – just like when I photograph for a book. But then I had to translate it into a different narrative format, like the one the book offers. It also was the first of my personal books where I had took on the role of creative director. In the beginning it was a struggle. But when you then understand how to fit it into a book, you simply benefit from what the format offers you: in this case more space and time to read, to reflect, to leave and return to it, a more intimate, more personal engagement.

I suppose that if I have to look for what these projects have in common, it’s always the same: visual and production research linked to a concept, the search for a balance of the three, constant empathy with the characters, the reader, and the sensations that they can have or that I want them to develop with their reading, a coherent justification for each decision made, a balance between the conceptual and the sensory, and a great responsibility in tone and content since I usually touch sensitive topics.

JC: Given you’re so invested in the photobook, whose photobooks do you particularly enjoy? What are your favourite books and why?

LA: Books that I like – not the best books: I prefer those books that you have to “chew on”, books where you cannot turn the pages quickly, that make me “stop” to read, to analyze, to understand. I like stories that can be explained to me in two sentences but then have used 200 pages to develop. I like it when there are several different elements. They do not always have to have text. But I do have a certain fascination for when disparate elements fit well. And the design has to be balanced and at the service of the story.

I have a certain weakness for archives, for the anthropological, the strange, the human. Quite often, I also like the opposite. Beautiful books, printed with very high quality in which you can lose yourself in a photograph… But I almost find that to be an experience more similar to what you have in an exhibition.

One thing that I often look for in a book, and especially in my own books, is that when I touch it has to be solid. That does not mean that it is a hardcover, but that has a certain consistency between what it says and what it is. I also like books that take a risk in some element, but I cannot deny that I have a tendency towards the classic and elegant at the same time.

That is why books published by Xavier Barral often fall into my hands with pleasure; I also follow practically whatever they do, authors like Christian Patterson, Sophie Calle, Will Steacy, Rob Hornstra, Rafal Milach, Taryn Simon, or Broomberg and Chanarin. Although I consume a lot of books, I am not a collector. So often the books I buy are for research reasons, for a certain fondness of the story or the author, or because – sometimes, I feel I have no choice but to take it home.

JC: Spain seems to have evolved into one of the new powerhouses of photography, both in terms of the book, but also just in terms of the photography emerging from there. Can you talk about the scene there, how things evolved and blossomed so much lately?

LA: Since I developed myself and my career abroad sometimes it’s hard for me to keep up with the scenes as we are all very much blended nowadays. However, since modern culture in Spanish is intrinsically related to our repressive history, on the one hand it’s true that our generation has found itself with certain disadvantages compared with other societies with a longer tradition of freedom — such as the French one. But at the same time our youth gives us a freshness and freedom of innovation that can be seen in the desire and amount of high-quality projects that are taking place nowadays.