Every once in a while (and it’s typically a long while), a book comes along that blows my mind. Typically (and maybe that’s why it’s a long while), such a book offers me more than merely cerebral insight (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

Three of the four books that were able to do over the course of the past five years that were written by women. The former scientist in me knows that four books is a small data set, meaning that any conclusions arrived at from this number stand on shaky ground. And yet…

I’m not well enough informed about writing, whether the fiction or non-fiction kind, to make pronouncements that are more than hunches. As a person, I like my hunches, even often enough they are completely wrong. As a writer, I like my hunches, too, but I tend to edit them out: you want to write what you write from a position of certainty because you take your reader seriously.

That’s bad writing, though, isn’t it? Did you notice the switch from “I” to “you”? Occasionally, a “we” might pop in.

Maybe given that I never properly learned how to write — I didn’t go to any writing program and thus should be considered an abject amateur — I mustn’t assume that all writers take their readers seriously. If writers think like photographers, some of them actually might not. But that’s not my concern, because you… I have to write following my own instincts, following what is true to me, the consequences be damned.

Those consequences might then have more to do with myself — not the writer self but the person self (and no, those two are not necessarily identical at all). But I might also arrive at conclusions that have the potential to be uncomfortable for readers.

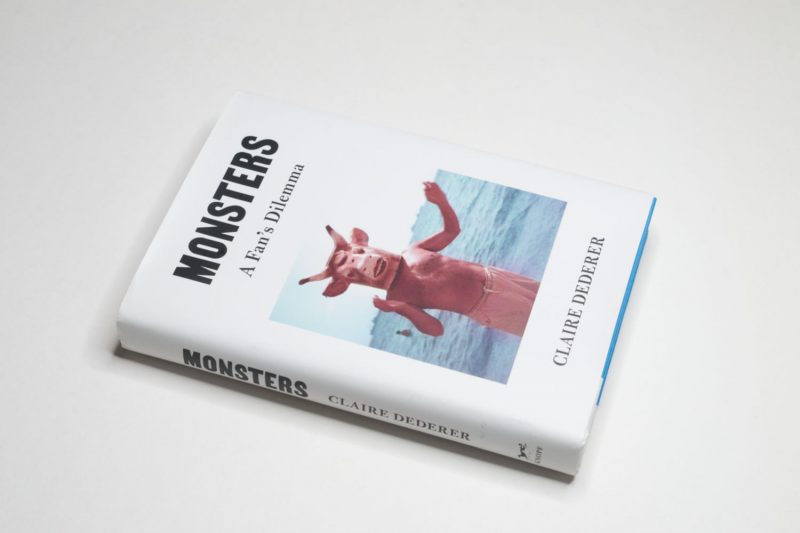

Claire Dederer decided to write a book about the people she calls monsters. In fact, we all might call them that. We all know the monsters, even if we might not apply that label. The monsters are famous artists who created widely admired pieces of art and who in their private lives engaged in terrible conduct.

The Prologue in Monsters (subtitled A Fan’s Dilemma) is entitled The Child Rapist, and the heading on top gives a name: Roman Polanski. If you had any doubt about what’s going to come in the book, that’s being brushed aside swiftly.

How does one or maybe should one deal with art made by terrible people? Can one still enjoy a movie by Roman Polanski, given all that’s known about him? Especially after the somewhat recent Me Too explosion, this topic has become widely discussed, (inevitably) leading to its own backlash. How do you deal with this?

The problem is easy to deal with when the person in question has never produced anything you enjoy. For example, I’m not into his movies, so it’s very easy for me to simply ignore Woody Allen. There’s no work that I possibly have to re-evaluate.

But I am fascinated with the work of Joseph Beuys, who now is very much tainted (Dederer uses “stained” in her book) by all of I read in a massive biography written about him (I’m not sure it has been translated into English). It’s easy to suspect that much like Neo Rauch, were he alive today Joseph Beuys would probably seek the company of far-right people, making dark pronouncements about today’s Germany.

These would be in line with the kind of utterings produced by someone like Ernst Jünger, a far-right writer who became well known for a novel that glorified the mass slaughter during World War 1. Jünger was far to the right, but he wasn’t a Nazi. The Nazis simply were too uncouth for him (this didn’t prevent him for serving them anyway as an officer in occupied Paris). When someone told me about Jünger’s writing, I read that book in question and thought it was pretentious, unreadable nonsense. Problem solved. For me anyway.

But it’s not so easy at all to solve the problem when there is something at stake for yourself: when you like the work but dislike the person. And that’s what Dederer dives into deftly.

“We tell ourselves we’re having ethical thoughts,” Dederer writes relatively early in the book (p. 24), “when really we’re having moral feelings.” These two entities are italicized, and they provide the nexus around which large parts of the following 233 pages circle.

It’s easy… Relatively easy… Well, we can at least have some sort of discussion around ethical thoughts because by definition ethics are communal, and thoughts and speech are connected.

Morality also is communal, but here, things become a lot more complicated. I mean what’s the difference anyway: morality vs ethics? Right? But anyway, the real problem is the feelings part. We all have them, whether we admit them or not. We all have some capacity to share them, even as that capacity can be severely underdeveloped (especially if you grow up as a man in a patriarchal society).

How do you reconcile that which can be spoken of easily (even if that speaking might contain any number of actually pretty bad elements, whether bad faith, virtue signaling, or whatever else) and that which cannot be spoken of easily at all?

And how do you even go about writing a book about a problem that sits at this very intersection of thought and feeling and that deals with art, maybe the one communal source of joy we have left, now that the combination of neoliberalism and neofascism have so severely degraded our democracies and societies?

Read Monsters! That’s how you do it.

I don’t necessarily want to discuss too many of the many, many details discussed in the book. To begin with, I don’t want to take away any of your enjoyment. Yes, I said it: while the book tackles a terribly complicated subject that contains gruesome human behaviour, it is incredibly enjoyable to read. At just the right moments, Dederer manages to throw in humourous curveballs — lest you choke on the general awfulness you might have just encountered.

But there also is the enjoyment of reading things that you maybe suspected or thought, and yet never heard anyone else say or write. “Part of the reason so much attention has been trained on men like Picasso and Hemingway,” Dederer writes, “is exactly because they’re assholes. We are excited by their asshole-ness. Wasn’t that what we saw with Trump?” (p. 109) This is from the chapter on geniuses, which is worth the price of the book alone for its insight.

There is a flip side to toxic masculinity (“genius”) and patriarchy, and that’s what women have to experience if they aspire to enter the world of art. Making art requires a considerable commitment, and that commitment often comes at the expense of all those who live around the artist. In a long and searing chapter, Dederer dives into what women have to deal with, women who might or might not have children and who thus have the added commitment of motherhood. Do you become a monster when you focus on your art — instead of your children?

This is subject matter that I have no experience with whatsoever. I decided not to have children because I suspected that I would be a very bad father. Of course, now I know a lot more about myself than I knew a couple of decades ago. But at times, I still find myself thinking that were I to have a child right now, I would be a bad father, given that I’m giving preference to something that good fathers know to avoid (I’m writing this article on a Saturday morning for crying out loud!).

Obviously, being a father is different than being a mother, and I can’t tell to what extent the chapter on motherhood and art will resonate with women. I suspect, though, that it will ring many bells — much like all the other chapters as well.

I’m not going to tell you about the conclusion (if that’s the word) Dederer arrives at in the book. You’ll have to read if yourself, in part because the real insight you will gain from the book is not so much the conclusion (which is brilliantly frustrating and insightful at the same time) as the way this author leads you through this impossibly complicated maze.

As you’re reading along Claire Dederer’s exploration of ethical thoughts and moral feelings, you realize that right at those moments, you’re growing as a person. At least I thought so (but hey, maybe as usual I’m just desperately trying to kid myself).

One last thought: it would be a real shame if after reading the book someone would still come away with the idea that there are those monsters, and then there’s the rest of us. In some ways, we all are monsters, even if some monstrosity obviously is a lot worse. We need to learn how to navigate that continuum.

Given that we approach all of this with ethical thoughts and moral feelings, and given that even in situations which aren’t about monstrous people, those two usually are not being made to speak to one another, too often discussions in the world of photography fall short. Just take, for example, all those discussions around appropriation and how none of those ever go anywhere — leading them inevitably to the courts (those are not the places where art should be discussed).

In much the same fashion, terrible art can be made by OK people. And terrible people can make lousy art. We all know. (I don’t want to give any examples, because almost inevitably the fact that I mention someone and their work will overshadow everything I wrote here.) In those situations, the insight provided by Claire Dederer in Monsters can also help.

We need smarter — and by that I mean a lot more considered — discussions in the world of photography, and we’re not going to get them until people will understand and deal with the conflicts between ethical thoughts and moral feelings.

Furthermore, in the end, it’s not so much about the art in question anyway. It’s all about us.

Oh well, I gave away the conclusion after all.

What a brilliant book!

Very highly recommended.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!