The Weimar Republic coincided with one of photography’s few major inflection points. As a consequence, no other location propelled photography forward quite as much as Germany during its ill-fated attempt to establish a democratic society. The Bauhaus whose 100th birthday is being celebrated this year provided a large section of the laboratory in which photographers worked on expanding what pictures might look like and what could be done with them.

But of course, there were other non-Bauhaus affiliated artists such as, famously, August Sander or Karl Blossfeldt both of whose main ideas originated in 19th Century thinking but who allowed themselves to see the potential of their work truly blossom. For a variety of reasons, Aenne Biermann is a lot less well known. To begin with, after a period of less than ten years of intense photographic activity, the photographer died in 1933 at age 34. Large parts of her work — prints and negatives alike — are considered lost: the family was Jewish, and her widower was unable to save anything other than bare necessities when emigrating.

An autodidact, Biermann is considered part of the New Objectivity movement, even though as Hans-Michael Koetzle points out in his afterword to the newly reissued 60 Fotos, this label for sure is somewhat debatable (much like most labels are). While the hallmarks of New Objectivity are present, so are photographic approaches that are a lot less cerebral and a lot more felt, such as in the photographs she took of her two children.

This book was supposed to be a part of a much larger series of books entitled Fototek, devised and partly realized by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold, the former an art historian and journalist, the latter one of the most important graphic designers of the 20th Century. There is an ad in the book that lists of eight existing and planned books. The first one, also entitled 60 Fotos and produced by László Moholy-Nagy, has become famous. The six other books never appeared, which is a real pity. El Lissitzky‘s 60 Fotos (book number six) would have been marvelous, as would have been book number 3 entitled The Monstrous (dealing with the idea of kitsch in photography).

Biermann’s 60 Fotos follows Moholy-Nagy’s in style and spirit, offering 30 pairs of photographs, many with a pithy caption added (in German, English, and French). Unlike in the Hungarian Bauhaus teacher’s case, the focus is solely on straight photography. There are no photograms or collages. In addition, perhaps not surprisingly Biermann’s book is a lot less didactic than Moholy-Nagy’s, a lot less cerebral.

In the world of contemporary photography, pairings of pictures are often produced in so-called conversations between two separate photographers. There, more often than not the pairings are based on a “this looks like that” or a “this is that” approach. Both 60 Fotos books push this rather simplistic idea further, by offering unexpected pairings. This is where things get interesting and enlightening. For example, pictures 21 and 22 are both called “Fried Egg”, but only 21 shows an actual fried egg in a pan. Twenty two shows the face of a jolly looking man with a rather round face. Even without the captions, the effect is striking and also quite silly.

There are many other pairings that have much to offer. Pictures 51 and 52 show a close-up portrait of a woman and a man, respectively, who each look into the camera as if they were facing a lover. Ten images before, a very New Objectivity still life of three apples is paired with the portrait of a woman wearing a monocle. Many of the photographs show microscopic close ups of minerals — in the late 1920s, Biermann had been tasked with making such pictures by a geologist.

It is heartbreaking to imagine the what ifs. What if this artist hadn’t died so young from a liver disease? What if so much of her work hadn’t been lost as a consequence of her husband’s forced emigration? What if…. To imagine that the pantheon of 20th Century German photography would now feature Aenne Biermann besides August Sander and the various other men… Maybe the reissue of 60 Fotos can help to at least remind the world of photography of this singular talent whose work can easily hold its own next to, say, Albert Renger-Patzsch’s.

Highly recommended.

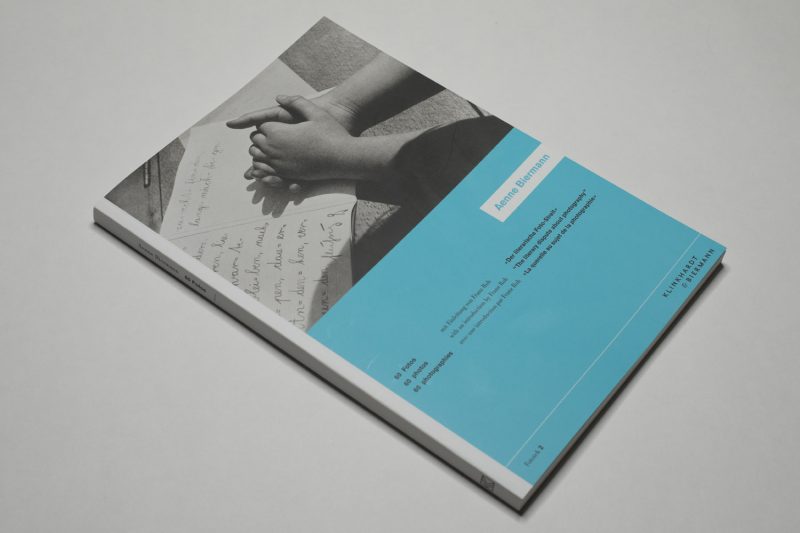

60 Fotos; photographs by Aenne Biermann; essays by Franz Roh (from the original edition) and Hans-Michael Koetzle (for the reissue); 104 pages; Klinkhardt & Biermann; 2019