One of the most interesting properties of photography is that the more you attempt to force meaning onto it, the less it will conform to it. Despite its technical nature and apparent degree of descriptiveness, photography works best when someone understands its limitations and gently works with and around them.

In effect, photography is most effective when it’s used to create what in the German language is called a Stimmungsbild, a term that photographically speaking does not make sense. Stimmung translates as mood or atmosphere: it’s that which photographs expressly are unable to depict.

Through combining them in such a fashion that their individual voices assemble like a choir, a collection of photographs can forcefully evoke an atmosphere in ways that rival (possibly surpass) other forms of art.

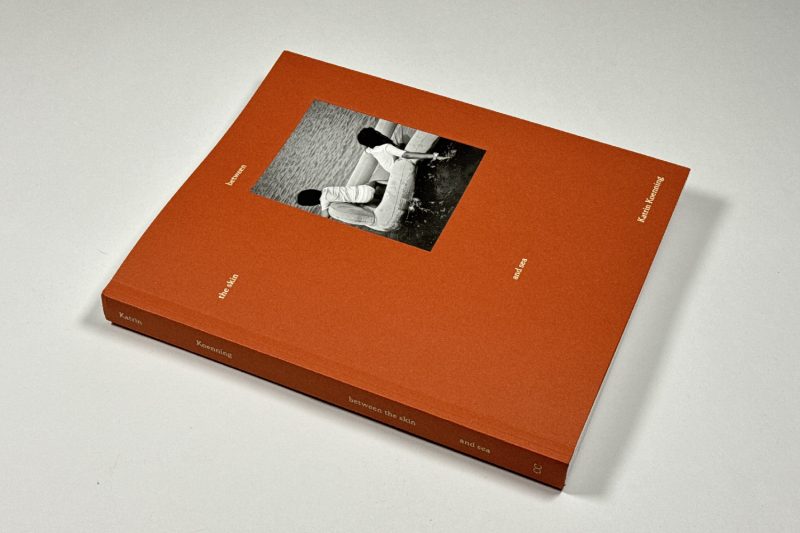

One of the reasons why description is such an impotent approach to photography criticism is based on the above: if you describe photographs, you do not in fact either engage with them or acknowledge what they do. If I went through Katrin Koenning‘s between the skin and sea and described the photographs, you would still have no idea what the book actually does.

In fact, I don’t envy the poor person at the publisher who had to describe the book. The best description of this book (and many others) would be: “just have a look at the book with an open heart, and you will see!” Obviously, you can’t sell books that way; but then it’s not clear to me whether talking about “tales of entanglement, relation, connection and intimacy” that “unfold” does the job.

That’s the thing with photographs: they need you to see; a Stimmungsbild defies language. Or rather, it defies description. Someone more gifted than me who knows how to use language to create a Stimmungsbild could conceivably assemble something that would approach between the skin and sea. But that would then be its own piece of art, one that evokes the mood of this book using text.

How does one go about living in difficult times? Well, I don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows (the fascists pretend that they know, but they only know a lot less than the rest of us: strength isn’t strength if it denies its own weakness). I haven’t spoken with Katrin about this, but I am certain that she would tell me that she doesn’t know, either.

At least that’s what I’m gathering from the book, because as far as I can see it was made from exactly that position: from finding oneself adrift in a sea of impossibility and uncertainty, the sea that stared washing over all of us maybe a decade ago (was it then?) and that since has not receded.

And I don’t mean that literal sea, some of which can be found in Katrin’s pictures, even though, yes, if you really want to by all means think about that sea as well (the amount of literalness in the world of photography has been driving me crazy for a while).

If you think about it, you could view the recent pandemic as a metaphor that became its own, real-life threat. Appearing seemingly out of nowhere, it put an initially puzzling danger into the air, and it pitted us against each other: you might be sick or at least might get me sick, and I don’t want to die from it.

I don’t think that it’s fair to say that the pandemic brought out the worst in us; the fascists had already done as much. But it amplified what had been in the air (not literally); and I am convinced that the fascists reacted so forcefully against our collective efforts to bring it under control because they sensed the disease’s potential.

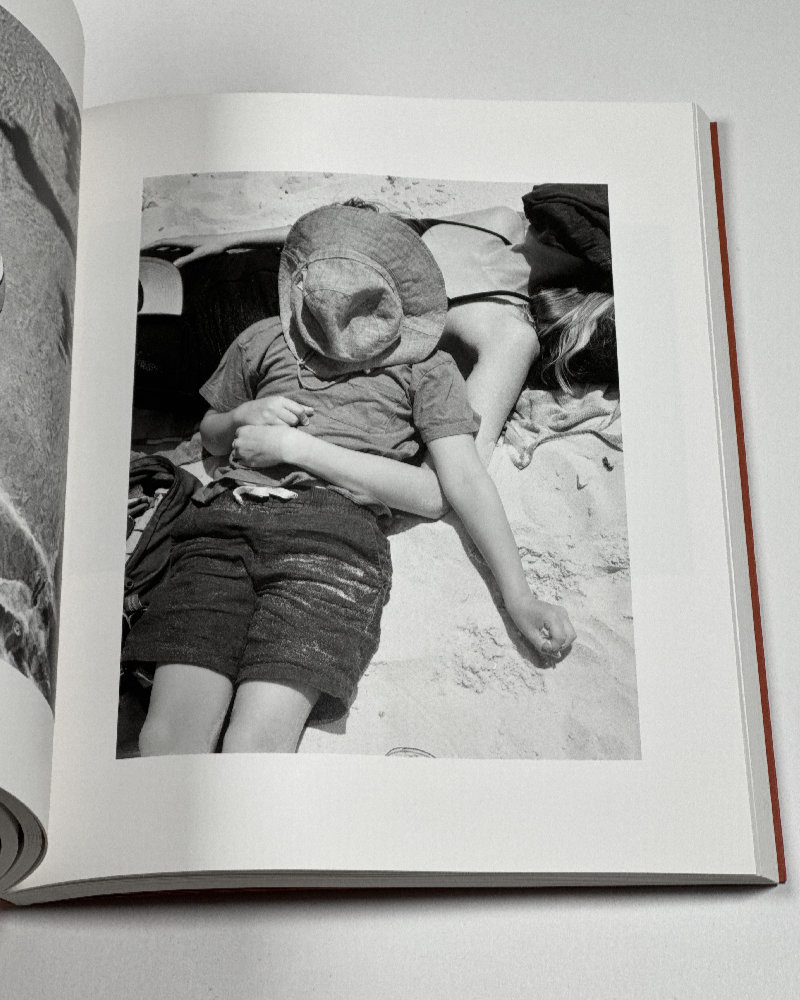

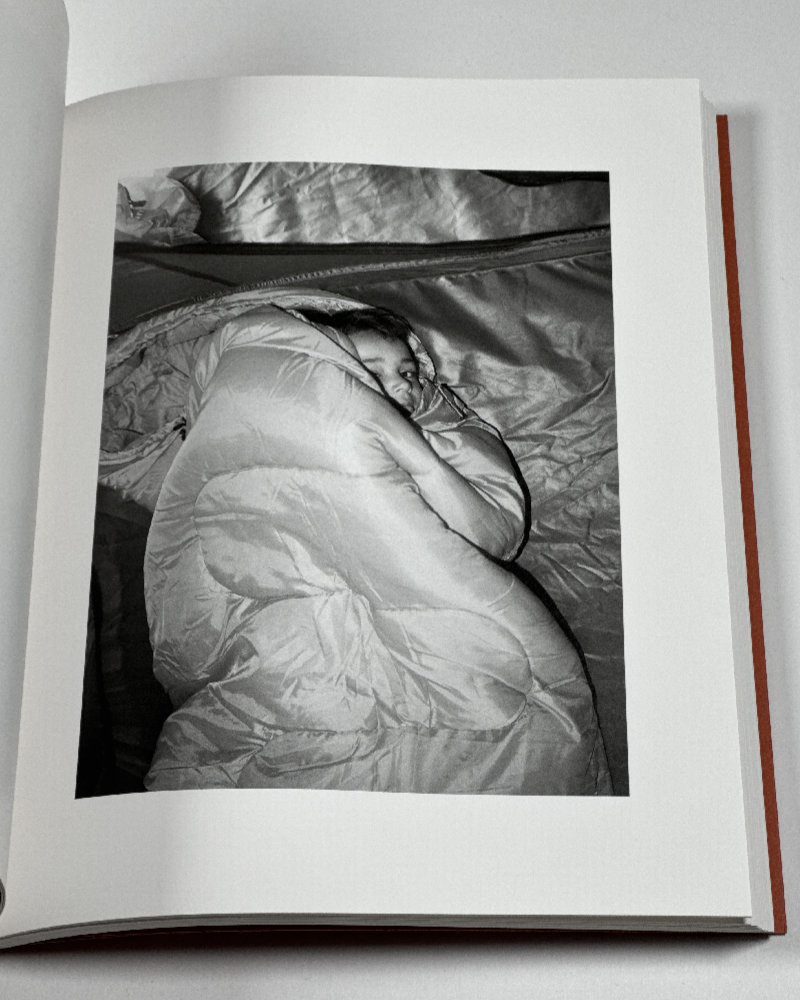

between the skin and sea is filled with a dread that cannot truly be named because it’s more than what was produced by the pandemic. It’s difficult to remember this now, but there also was a real beauty to the many manifestations of solidarity that emerged at the time (at least until we all got so tired of living under that particular Damocles sword).

The book contains frequent allusions to those as well, to the reaching out and being with each other, realizing that the physical distance we would have to observe only served to remind us of the closeness we felt with each other.

This is the kind of book that could only have been made by a mature artist, someone who has been in this world for a while to know about her own and other people’s vulnerabilities, someone who has had her fair share of suffering and disappointments, someone who knows how to pull a widely felt sentiment out of her innermost emotional core.

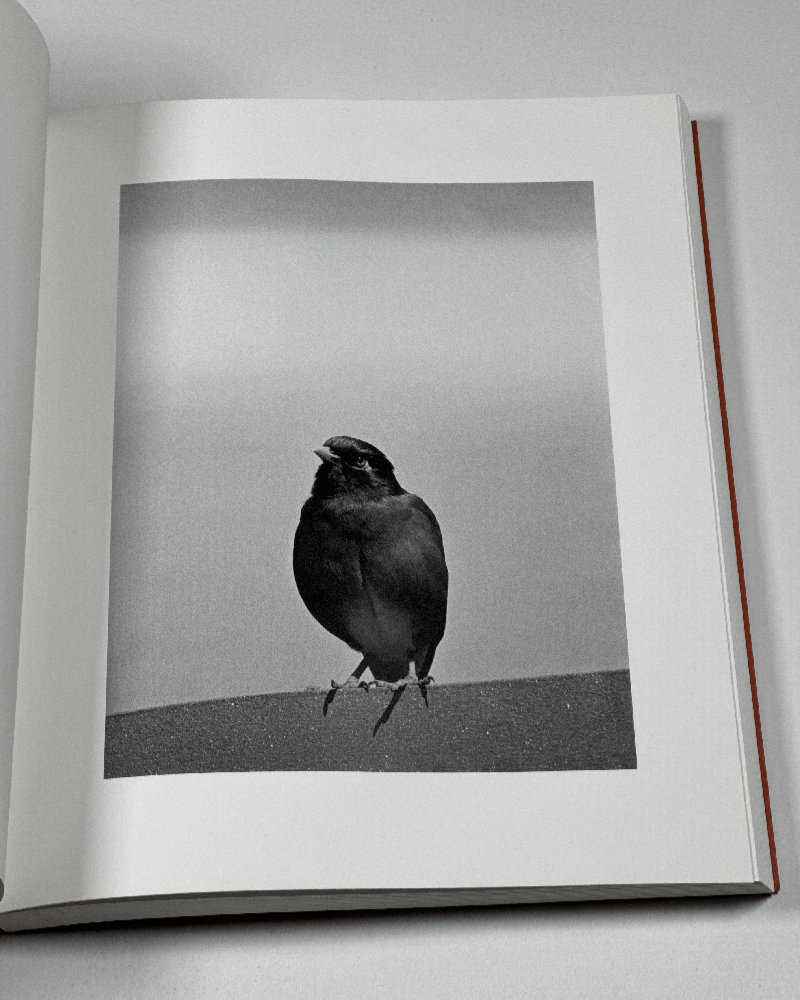

It’s a book that is mostly inhabited by innocent creatures — children and animals, and the few adult figures seem lost and uncertain how to proceed. (By the way, really good photographers don’t shy away from making really good photographs of cats and putting them into their books.)

If by now you don’t want to race to get a copy of between the skin and sea, it’s unlikely that anything else I might write will sway you. That can’t be the idea of criticism anyway, to sway people. After all, that’s not the idea of art, either.

Art isn’t trying to convince people of something in the way that you might get convinced to eat broccoli because even though you hate the taste you know that it’s good for you.

Instead, art has to remind us of what little shards of shared humanity we have left. Photographs ask us to see — and then to feel (or rather the good ones do; the others are still only pictures of sticks and stones that no highfalutin statement can salvage).

And this is the age where we have to force ourselves to look, to see, to feel — and then to act. For things to get better, we will have to start out at the smallest scales — a little kindness to a stranger maybe, or a smile.

Highly recommended.

between the skin and sea; photographs by Katrin Koennings; 188 pages; Chose Commune; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!