I happened to look at Anne Morgenstern‘s Macht Liebe for the first time after having spent some time on Instagram. This made for a jarring experience. Larger parts of Morgenstern’s photographs would not be able to exist on Instagram simply because they run counter to what the company euphemistically calls its “community guidelines”: essentially a framework that permits complete freedom only to straight white men, some freedom to straight white women, and very little — if any — freedom to anyone else.

Obviously, we could all just leave Instagram. But the company and its app are not any more the problem than Donald Trump was. They’re merely symptoms of an underlying culture that values one particular type of body at the expense of everybody else’s and that equates nudity with sex. If for a reason that is pretty much entirely out of your control you happen to have a body that does not conform to the widely demanded norm, then, well, you’re out of luck.

You’re not only out of luck because you will be discriminated against in a number of ways (whether on Instagram or in our larger visual culture); you’re also out of luck because as a society we’re really bad at talking about bodies and what it means to inhabit one. If you’ve lived long enough it’s not difficult to conclude that almost every person has some problems with their body, and yet almost nobody is able to vocalize them. Instead, we all bottle them up. When someone attempts to do it anyway, let’s say on Instagram, we might double tap to “like”, maybe we leave a comment in some form, and that’s about it.

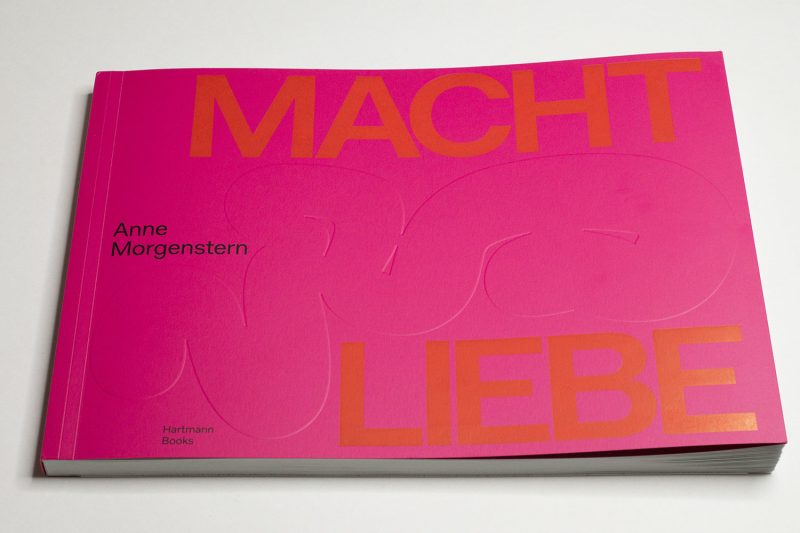

Open Macht Liebe and you’ll encounter a completely different universe. Or rather a version of our world that has shed all constraints and that embraces each and every body simply the way it is. Obviously, one of the reasons why the book is so good is because the photography itself is so stellar. Where Morgenstern’s previous books were already very good — you can find my reviews listed here, this new book feels like a quantum leap forward.

The photography feels contemporary — you can tell that the artist is very much aware of the current visual discourse. At the same time the photographs don’t feel as if they were made for the academy: that cliquish group of art photographers and curators who make work only for themselves, without any regard for the larger world — even as they very much pretend to do the opposite of that. Instead, these photographs are very much alive: they breathe, they’re open, they often are playful, and yes, they’re very beautiful.

The photographs cover a variety of people and objects. There are portraits (photographed with a sense of generous tenderness that is very, very rare these days); there are details of body parts; there are still lifes; there are photographs of animals; there are photographs that evoke snapshots without losing focus of the task at hand.

And there are bodies, large numbers of them, all kinds of shapes and forms and ages and sexual orientations and gender identifications and whatever else. It is the strong sense of acceptance mixed with playfulness that prevents the work itself from being didactic. As a viewer, you’re invited to look and become a part of what is on view, even as for sure every viewer will find their own limit to how far they might be willing to go.

In addition, the object itself, the book, embraces what can be done with this particular form and elevates it beyond your regular monograph. Each spread offers space for four vertically taken photographs, even as that space is not always completely filled. For example, the book opens with a spread of three pictures, followed by four, which are then followed by two. Occasionally, there is a horizontal photograph instead of two vertical ones, so the fourth spread shows one horizontal pictures next to two vertical ones.

While this might sound confusing when described with words, the experience of the book is the complete opposite of that. The combinations of the photographs and the effect achieved through the variations creates a very powerful visual game, in which each and every photography is made to work in some form of harmony with its neighbours. This is no mean feat, given the work that must have gone into constructing this sequence of groupings that, in turn, build up through their sequence to a very powerful whole.

I can’t think of another book that employs this method as successfully. After all, one of the possible drawbacks of this type of book building is that there is the risk of things becoming just much too cerebral or too centered on the bookmakers’ cleverness — instead of on the photographs and their overall message. It is possible that these photographs themselves prevent arriving at such a conclusion; but the edit and design team — the photographer along with designer Claudio Barandun — did an incredible job.

Macht Liebe feels like a welcome addition to Hartmann Books‘ usually elegant but also maybe a bit too predictable stable of books. Don’t get me wrong, I like a lot of their books. But it’s wonderful to see a book break out of the usual a little bit too quiet restraint and throw something wild at you. Macht Liebe is wild — in all the best ways. Its German title is nifty. It translates as either “make love” or “the power of love” into English. As with all great books, it’s the small details that matter.

It’s impossible to know what the rest of the year will bring in terms of photobooks. It’s possible this book is just the first out of many great books this year. Or maybe it will remain that one book that at the end of the year made the biggest impression on me. Whichever it ends up being, Macht Liebe is absolutely brilliant — one of the best contemporary photobooks in a long time.

Highly recommended.

Macht Liebe; photography by Anne Morgenstern; essay by Danaé Panchaud; 192 pages; Hartmann Books; 2022

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 5.0

Ratings explained here.