Masami Yamagiwa has been living at Atelier Yamanami since 1990. According to the Atelier’s website, he “likes his daily tasks such as cooking, washing, cleaning and collecting waste paper for recycling, at a fixed time every day. For him creating artworks is one of them. […] His most important work subject is called ‘Masami Jizo’. ( ‘Jizo’ is a small stone statue representing bodhisattva, wearing a red bib.) Masami Yamagiwa has been creating ‘Masami Jizos’ for more than 20 years, and the number of the statues he made now exceeds over several hundred thousand.”

Rinko Kawauchi encountered Yamagiwa at her first visit to the Atelier in 2018 as she details in her afterword to Yamanami (やまなみ). Upon entering, she came across his booming voice singing Happy Birthday. On top of making a huge number of ‘Jizo’ sculptures and going about his daily chores, Yamagiwa has also memorized the birthdays of every person at the Atelier, inhabitants and staff alike. On their given day, Kawauchi notes, “first thing in the morning […] he walks up to that person and sings the song.” (quoted from the afterword)

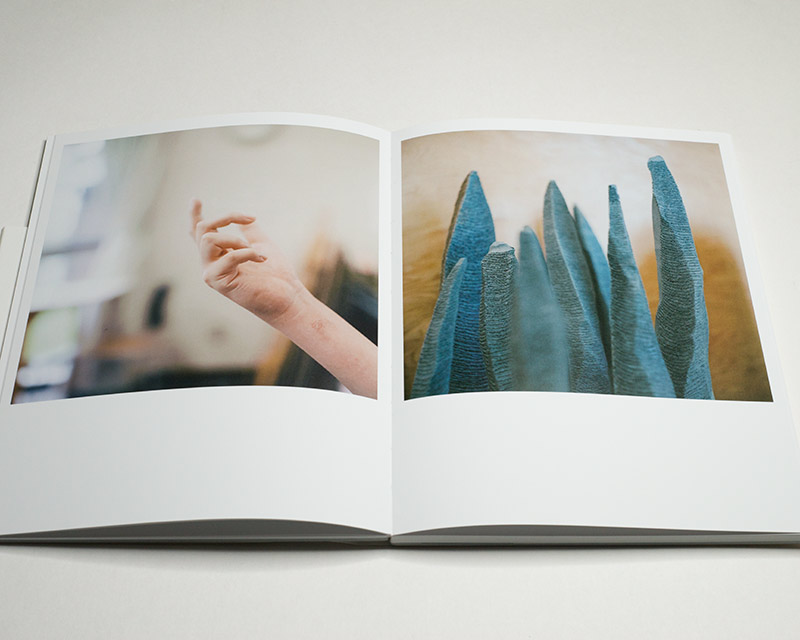

There is a photograph of some of the ‘Jizo’ in the book. There must be dozens and dozens of such figurines, but due to the camera’s limited depth of field, only perhaps three dozen of them can be seen clearly. A viewer familiar with Kawauchi’s work might detect the artist’s visual signature at play right away, with its heightening of what is being paid attention to. In this Japanese photographer’s pictures, every little detail, however significant or insignificant, becomes a little miracle.

Another photograph of some artwork at first looks like a collection of leaves from an aloe plant. But then you realize that it must be a sculpture. In the index at the end of the book, the photograph is revealed as Hideaki Yoshikawa‘s ‘Eye, Eye, Nose, Mouth’. What initially look like dots reveal themselves as tiny faces that the artist uses to cover his artworks with. There is a photograph of Yoshikawa in the book. Holding a wooden (bamboo) tool in his right hand, you can see him work on an object that bears similarity to the ones in ‘Eye, Eye, Nose, Mouth’. The tip of the tool is placed in the center of the frame; as a viewer, you can feel how all of the artist’s concentration is channeled towards what for other people might be an insignificant detail.

Most photographers are aware of the fact that taking pictures of other artist’s work creates a conundrum. A very well-known German artist once told me that he stopped taking accepting commissions by architects, given that in the photographs, so much attention would be garnered by the buildings — instead of the photographs themselves. Kawauchi clearly didn’t seem to concerned about this problem. Reading her afterword and having followed the trajectory of her career, I’m not even certain she would consider it as such. When you see her photographs you know why. They are very much her own, betraying her very specific artistic sensibility, even where they focus on artworks created by other people.

Atelier Yamanami is no ordinary shared art space. Instead, it houses almost 90 people with disabilities who are encouraged to channel their creativity into artistic outlets — much like Masami Yamagiwa and Hideaki Yoshikawa. Its website features the artworks created (with text in Japanese and English). You might want to set aside some time to look through what is being on offer.

With a little disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Kawauchi spent three years photographing at the Atelier. The outcome is nothing but magical and endearing. As a viewer, you can feel an incredible amount of tenderness at play. Thinking about the photographer’s approach, I have been imagining a fly-on-the-wall approach (what an ugly image, though): being observant, while resisting the temptation to interfere too much. But many of the photographs show a closeness to what is being shown that is not just physical but mental as well. The photographer clearly must have felt a very deep connection with what or who was in front of her camera.

In her afterword, Kawauchi conforms the suspicion a viewer might have arrived at earlier. “Laughing with the person in front of me,” she writes, “or being absorbed by the great concentration they put into working, allows me to rediscover the space within me.” If only all those other photographers supposedly collaborating with their subjects would realize the importance of this sentiment! “It is like a mirror,” Kawauchi concludes, “everyone reflects the light illuminating each other.” (For more details on the beauty of Kawauchi’s afterword, please see the article I wrote for my Patreon.)

After As It Is, a book about the birth of her child (reviewed here), the Japanese artist has now produced another stellar photobook. Kawauchi has clearly found back to the visceral strength of her early work, which has now been infused with all the insight you gain from having lived on this planet for a while. Yamanami not only proves all those people wrong who claim that photographers produce their best work early on. It is true, for many photographers their early success traps them in that narrow space where everything merely is but a weak copy of something already done.

But photography — as much as anything else that can be art — gains much from an artist’s maturity, assuming they are able to listen to the lessons provided by early success and to see the world anew every day. Of course, this can only happen if — and only if — they are paying good attention to it.

It’s hard not to see Yamanami as an absolutely essential masterpiece that I’m sure will hold a special place in Rinko Kawauchi’s career trajectory.

Highly recommended.

(Please note that I’m supplying a link not to the original publisher, but to a Japanese distributor whose site offers English text and which offers convenient and very reliable shipping to destinations outside of Japan. Please also note that the books comes with two different covers — essentially different wrappers around the hardcover, which are referred to as “A” and “B”. My copy is “B”.)

Yamanami, photographs by Rinko Kawauchi; essays by Rinko Kawauchi and Masato Yamashita; 104 pages; Shinyodo; 2022

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 5.0

If you enjoyed this review, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles and videos about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!

Ratings explained here.