Last week, I argued that in light of the fact that Donald Trump is going to be the next president of the United States, the world of photography (“photoland”) might want to take a good, close look at itself and consider changing things up a little. To what extent change is going to happen I’m not sure. After all, however limited and outright self-serving large parts of photoland actually are, however limited the options are for many of those eager to be a part of it, the current system works well for enough people (much like politics itself). And many of those people will resist change.

It’s really up to all of those for whom the system does not work so well to demand change, and to make it happen. I believe that there will be enough people who are part of the system, in whatever capacity, who will ask for and work towards change as well. That change will have to entail breaking out of established structures, to find new ones. This is not an impossible task. The gallery system, for example, has not always existed the way it does now. It was established not so long ago. In a similar fashion, the kinds of discussions around photography now happening online, of which this site is a part, have also been started not so long ago.

When I started working on the earliest version of this site, I didn’t have a master plan. I believed (and still believe) that the internet was (and is) a great way to look at and discuss photography, and whatever I could (and can) do to contribute I would (and will) want to do. It hasn’t always been easy working on this site. I have at times been wracked by doubt and uncertainty. But I also know that that comes with the territory.

Given last week’s piece did not include any specific examples of what could be done differently, I thought I’d follow up by doing that. I will say this, though. The key to change in photoland is to get rid of the expectation that there will be easily available solutions. While the ultimate goals can and probably should be crystal-clear, the paths getting there are not. These goals might include, but are certainly not limited to, reaching out to much larger segments of the population, including and reflecting a much wider range of voices beyond the often narrow range of middle-aged white men (the irony of me being exactly that does not escape me), and more.

If what I did with this site can in any way serve as an indicator, doing what one believes in is the thing to do: a goal in mind, an uncertain path ahead. What makes good photography good — an absence of clear-set answers in the presence of the right questions — might here help get things off the ground as well.

How then do you reach other people, people who are not part of photoland? How do you reach those who might be subjects of photoland, subjects of any of the products produced, first in the pictures, and then maybe in the books?

Two years ago, I wrote about Paolo Woods and Arnaud Robert’s Haiti work. There was a book, State, one of those standard photobooks. Really, nothing wrong with that. I quite liked the book. But it was also a book whose price was way beyond what many of its subjects would be able to afford. Not the rich people depicted therein, no the vast pool of the population in Haiti. So Woods and Robert made a version of the book for Haiti, produced there, with text in the local language. And they made an outdoor exhibition, putting up poster-size copies of their photographs in a public space. You can find all the details in the piece I published.

There’s a video at the top of the Just Another Photo Festival website that ends with the words “We take photography to the people.” After all, all you need to do just that, to take photography to the people, out of the white cubes and the Grand Palais, is a projector, some electricity, and a screen to project on (a big piece of white cloth will do). And then you’re in business.

Mind you, Just Another Photo Festival (JAPF) is exactly not that. It doesn’t offer the usual circus (portfolio reviews, talks, etc.). It brings photography back to what the medium does best. It brings it back to the photographs themselves, and these photographs are shown to people who otherwise wouldn’t have access to them. Started by Poulomi Basu and CJ Clarke, JAPF shows what you can do if all you have is a simple, basic idea and the will to make it happen.

While the Trump presidency still is some time off, other countries have experienced having to deal with toxic governments already. Right now, Trump is merely following in the footsteps of the authoritarian governments currently in power in places as diverse as Russia, Turkey, Hungary, or Poland (to name just a few). It’s easy to look at Canada right now and think there’s much to be admired there, but things looked a little different under the previous prime minister, Stephen Harper.

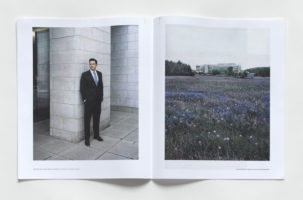

In an email to me, Tony Fouhse writes that he photographed Official Ottawa as “a reaction to the chill in the capital (and across the country) brought on by Stephen Harper’s policies and approach.” He then published the work using newsprint, which he gave away for free: “I have noticed a big difference in how my work is approached and consumed when it is on a gallery wall vs being distributed at random for free. People go into a gallery primed to look at art, they are in that mode and, so, regard the work from a mind-space that is ready, if you know what I mean. Then I’ve seen folks bump into the Official Ottawa newsprint and, more often than not, flip through, look confused or bored, set it aside, flip open and begin to read the local tabloid newspaper.” There obviously is the fact that the context in which your work is being seen matters.

Taken outside of the context of the white box, your pictures will not be treated any longer they way they do when they hang on those walls, with a price list available at the reception desk. In other words, to reach those not part of and not familiar with photoland might require a rethinking of one’s strategies. And even ignoring that, there will always be the possibility that something does not have the intended effect. Of course, that can also happen inside photoland. People might prefer their local tabloid newspaper.

“This can be a bit dispiriting.” writes Fouhse. “But I have come to understand that once you try to reach outside the box the results are less assured. But I have always held assured results with a certain amount of contempt. What, after all, is the point in executing a plan designed to arrive at a foregone result (unless you are an engineer or a manufacturer of widgets, or something)?” To me, that would be the key here: Once you’re outside the white cube, things will look a lot different, and you will not run into the same reactions. But that’s really the beauty of it, because it opens up possibilities.

As stifling as being part of that narrow white-cube-plus-photobook scene is for most, there also is the comfort that you know what to expect. Your friendly reviewer will write the right things about those working-class people in your pictures — a world that neither of you is actually part of.

Consequently, a change in thinking is required, not just about how to break out of photoland. What does artistic success actually mean? What can it mean? What should it mean? In its current form, photoland is unlikely to offer much, if any success, to those inside (if you haven’t done so already, you certainly want to read this piece). If you get some success, you know what it looks like (some blog featuring your work, your book on any of the five million short lists, or whatever else). But outside? It’s not so clear. And that’s the beauty of it.