Hardly a day goes by without some photobook arriving in the mail that attempts to impress me with an overly complex and/or convoluted attempt to tell some usually quite mundane story. You know the book: pictures are all over the place, in tandem with the photographer the designer appears to have consumed way too much coffee, and the production involves all kinds of gatefolds and pages of various sizes and papers.

That approach can work when it’s done well and when it’s appropriate. I have reviewed quite a few of such books. But now you can go to workshops where such a book will be made for you, regardless of whether or not the photographs in question and the project itself actually require such an approach: that’s just formulaic, reducing what can be a very valuable way to make a photobook into a cheap gimmick, a gimmick used to attempt to dazzle the audience (which, granted, appears to be easily dazzleable).

Speak with photographers, and all you’ll hear is their interest in “narrative” (I’m placing the word in quotes because many photographers don’t really know what the words means). Mention the word “catalogue,” and you’ll get looks as if you just showed up at Count Dracula’s house with a bunch of garlic and a cross. Frankly, this is an absurd situation, which I hope won’t last much longer.

The reality is that even in the most complex narrative-driven books that I enjoy very much the quality of the photographs themselves tends to be at a high level. In other words, I personally prefer photography that is visually engaging (if not more). There’s nothing more tedious for me than to make my way through some interesting story that is told with mediocre or lousy pictures.

In the case of photography that doesn’t fall into the category of narrative-driven work, this would appear to be a widely accepted statement: you don’t want to look at lousy pictures. How or why so many photographers interested in narrative-driven work somehow appear to have forgotten this aspect of photography is not clear to me.

I’m hoping that the pendulum is now going to swing back and that renewed focus will be put on photographs, on making photographs that are visceral or beautiful or stunning or moving or whatever else they can be.

After all, at its very core photography should be about the excitement of experiencing in the medium’s particular form the end result of having truly seen something or someone. It’s not just about looking, and it’s also not about recognizing — it’s about seeing, about discovering. And that excitement, that joy can simply come from what the camera does itself, when it’s being used under the right circumstances, by the right person — the right person here the one who directly taps into her or his visual cortex.

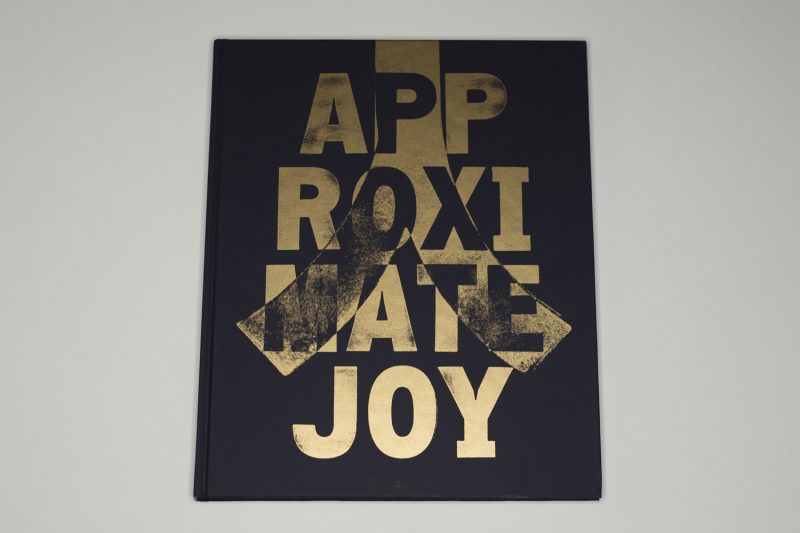

It is repeated exposure to Christopher Anderson‘s Approximate Joy that triggered the above for me. The book is really “only” about the things a camera can do when in the hands of a gifted photographer, but, boy!, is that a lot! I have read the way the book is being described by its photographer, publisher, gallerists, and others. But honestly, I don’t buy any of that stuff. The photographs might have been taken in China, but they’re not about anything other than being made themselves, about existing as beautiful images.

You might wonder why I am so insistent about reducing them down to that. But I actually don’t think of stripping them off all the added verbal artifice as anything other than doing them — and the photographer — a service. A couple of years ago, I wrote an essay entitled Why does it always have to be about something?, and I stand by that piece to this day. Beautiful photographs ought to have the right to be just that, beautiful photographs, without requiring some verbal crutches. In fact, truly beautiful photographs such as the ones in this book don’t require any such crutches: their own sublime beauty almost resists being forced into what ultimately only is a simplifying Procrustean bed.

For the most part, the photographs in Approximate Joy are tightly cropped portraits of what look like pedestrians who are illuminated by very direct, mostly artificial light. Like the crescent of the sickle moon, contours of faces are being thrown into sharp relief against an often murky background. Most of the portrayed appear unaware of the fact that they have become photographic subjects, showing their faces in the kind of state common when being in public on your own: your face’s expression is publicly private, attempting not to betray too much, if anything, of what might be going on beneath the surface.

Our — the viewer’s — gazing at these faces allows us to project our own ideas onto these faces. Mind you, we don’t have full license to do so, given the photographic choices at hand here. We are guided in specific ways. And I can’t help but feel the photographer’s own joy of making this work here. These photographs are about nothing other than seeing and about crafting beautiful images — crafting here not in the tediously joyless Ansel Adamsian sense, but rather in a much more excited intuitive way (much like the difference between Christopher Kimball’s cooking show and Jacques Pepin’s, respectively).

Of course, you might point out that I have no way of knowing all of this. You’re right! Who knows, maybe Christopher Anderson did go to China to make some statement about the future or any of the other stuff mentioned in the verbiage around the work. Regardless of whether that’s the case, it doesn’t matter. The work itself, these sublimely beautiful pictures, demand to be taken for what they are: they are all about the joy of looking, the joy of making beautiful pictures. That’s it.

“That’s it?,” you might ask, “how can that be enough?” Well, of course it’s enough! It’s photography! It’s what we seem to have forgotten about photography, having seen all this stuff put on top of pictures, whether by photographers themselves, by editors, curators, writers, critics, educators… There is something to be gained by adding words to pictures, by talking about pictures, by putting them into context. But the adding of those words must not become the same formulaic tedium as the creation of endless amounts of narrative-driven books.

Seen that way, Approximate Joy is a radical book: its insistence on picture being allowed to be pictures should remind us of the essence of the medium and of the fact that beauty on its own is not something we should run away from. It’s something to embrace, something to cherish.

(At the time of this writing, the book is sold out. Let’s hope that there will be a second edition.)

Update (15 November 2018): There is going to be a second edition that can be ordered here.

Approximate Joy; photographs by Christopher Anderson; 120 pages; Stanley Barker; 2018

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 4.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.6

Ratings explained here.