Photography’s emancipatory power is understood best by those who use the medium to strive for a more just, equal society. There are two aspects to this power, which now have become firmly entwined. There is the power to be seen not as others see you, but rather as you see yourself. And there is the power to create the photographs yourself.

Very early in the history of photography, Frederick Douglass recognized and used the medium’s emancipatory power. He sat for over 100 photographic-portrait sessions at a time when the production of such pictures was a lot more of an endeavour than it is today. Douglass wanted a picture of his to look the way he saw himself. This was something only the camera could offer — engravers and painters inevitably distorted the way he looked: “Artists, like all other white persons, have adopted a theory respecting the distinctive features of Negro physiognomy.” (here quoted from Ernst van Alphen, Failed Images: Photography and Its Counter-Practices, Valiz, 2018, p. 70 — please refer to the book for details)

Van Alphen writes: “Douglass suggests that posing for a portrait performatively produces dignity. The image is not seen in terms of its likeness to the sitter, but as actively producing a truth about the sitter that results from his posing and other aesthetic elements of the image.” (ibid., p. 71; my emphasis) It is this very idea, the production of a truth about a sitter that is not dictated by anyone other than the sitter her or himself, that should be seen as the driving force behind self-portraiture.

It’s instructive to apply this idea to a number of well-known bodies of work that center on the idea of family (whether literally or somewhat metaphorically). Both LaToya Ruby Frazier and Nan Goldin included photographs of themselves in The Notion of Family and The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, respectively. In both cases, these photographs heighten the work in incredible ways. In contrast, in Larry Sultan‘s Pictures From Home or Doug Dubois‘ … all the days and nights, the photographers decided to remain behind their cameras: beyond dealing with basic family problems (that, let’s face it, we all have), neither Sultan nor Dubois had anything to battle with. For them, there was no need to employ photography’s emancipatory power.

The fact that the so-called selfie is so maligned in the work of photography stems not from what it actually is: a type of self-portrait. Instead, maligning the selfie ultimately is a power play by those engaged in it, especially when it’s done by someone who is a photographer: someone might have no problem with defining another person through a portrait they take of them, to express their own artistic sensibility. But when people photograph themselves, to share the picture, then that’s merely an expression of narcissism. How does this compute?

However much (actually little) I might have in common with so-called influencers who share selfies of themselves on social media, to deny that their endeavour is focused on asserting their power strikes me as possibly the worst possible approach.

I might have problems with the power in question, especially since it often ties in very deeply with consumerism. But the question should not be: why are these people so narcissistic? Instead, we should ask: why have we created a society where for many people an expression of power, an assertion of one’s self, is tied to consumerism? Have we, in other words, put too much emphasis on consumerism, while neglecting so many other aspects of what might constitute a meaningful life?

Asking this question leads us away from photography. But how good is talking about photography when all we do is to talk about the pictures and their makers as if all those connections to the world at large didn’t exist? Do we want photoland to be that solipsistic?

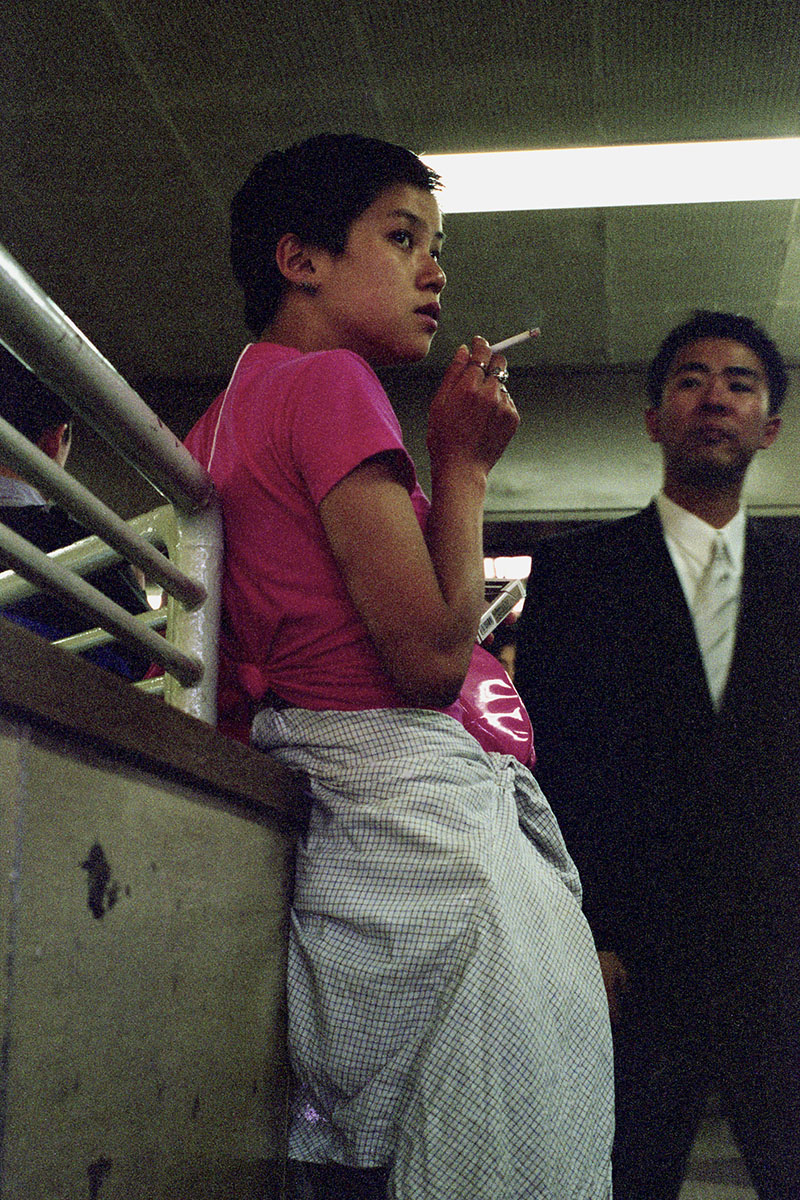

Yurie Nagashima — Rendez Vous (1994) from the series “Myself”

Another interesting comparison is provided by Masahisa Fukase‘s Kazoku [Family] and Yurie Nagashima‘s book of the same title (Korinsha Press, Kyoto, 1998; unfortunately, it is long out of print). In both cases, the artists appear alongside their families. But Fukase’s at times overly cynical photographic nihilism and his being a man in a very misogynistic society prevented him from understanding the emancipatory power of his medium: he had no need for it. The complete opposite is true for Nagashima. It is exactly the emancipatory power a camera can grant those who know how to use it that enabled her to powerfully talk about her own family dynamics.

Another absolutely thrilling example of how Nagashima uses the camera’s power is provided by Self-Portraits, a newly released collection of photographs. At the occasion of her retrospective at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2017, the photographs were shown as a 30 minute slide show with more than 600 images, spanning 24 years (1992-2016). In the book, they are distilled down to a smaller number, presented chronologically.

The earliest photograph shows a young, serious looking backpacker, her face turned to the camera, while the rest of her body is ready to walk off onto some trip. The following photographs employ a variety of approaches to the picture making that continues throughout the book: pictures of reflections in mirrors, pictures of the artist’s shadow, pictures that either used a camera’s self timer or cable release.

There’s a break from black and white to colour, and immediately, the photographs become more deliberate — deliberate in the sense that the artist appears to have started focusing on her intent. A lot of the posing now adopts conventions (if that’s the word to use) that culturally have become established as the ways young women are supposed to be photographed: as sex objects, offering themselves up to male viewers.

The very obvious control that Nagashima exerts over the photographs manages to have the viewer not fall into the trap of seeing a sex object but, instead, to think of the fact that what is presented is a convention, a convention that reduces half of the population to photographic passivity, to define them through the eyes of the other half (the sexualized male gaze).

The variety of the photographs also helps to drive home the point that what the viewer is looking at is a young woman taking back control. It is as if she was taunting viewers — “Hey, isn’t this what you want me to look like?” — while at the same time offering her own counterpoints, such as when lying on the floor of her apartment while being on the phone (possibly with a friend, as the pictures makes the viewer think).

Yurie Nagashima — Self-portrait with R and my mom (2002)

And then there are the iconic photographs, which somehow don’t even stand out that much in the book (such as the tank-girl picture). It’s testament to the photographer’s vision that everything fits together so tightly, that everything speaks so strongly of that main concern: her confrontation of a sexist society, using sexist photographs of herself just as much as pictures we could call punk ones (a Riot grrrl approach in photographs).

At some stage, the punk photographs take over, to eventually fall away, too. This is another break. Now, the viewer gets to see the first larger series of photographs that aren’t relying on some convention, whether sexist or punk. Instead, we see a young woman looking to define herself on her own terms. This is not to imply that the punk approach wasn’t her own. But it’s one thing to define oneself through a subculture, and it’s quite another doing so on one’s own terms.

And then that all ends, because there is a baby. There’s the iconic “fuck you” photograph Nagashima took while being very pregnant. Right after, there’s the baby, at first lying at the artist’s feet and then in her arms. Everything changes so much when there’s a baby. I wouldn’t know because I never had one, but here I can see it, in these pictures. Every picture now has the young son it, and every picture is about that particular relationship.

We see the young boy grow slowly, and we see the photographer making work that is as much about herself as it is about this other human being that, we notice, is always there. Young children require so much time. But the boy keeps growing, and ultimately, at a certain age, he drops from the pictures, and the artist focuses on only herself again.

When I wrote earlier about photography’s emancipatory power, that idea becomes very clear and apparent from this book. It is important to realize how broad that power can actually be. Different phases in the life of Yurie Nagashima played out very differently in the photographs. For example, the early rebellion against a sexist society gave way to an attempt to understand the role of the mother.

If you’re a member of the Japanese society, there is much to rebel against (assuming you’re the rebellious type). But I think that what is on view here will easily resonate outside of Japan, because it’s not like many other societies have reached a stage of complete equality for all its members (I actually can’t think of too many).

Yurie Nagashima — Untitled (2013) From the series “Vous me maquillez”

Looking at these photographs as a man (who grew up in a different society), I still feel a sense of kinship with an artist who is rebelling against conventions and restrictions put onto her. At the same time, I realize that the conventions and restrictions I reject are different — much smaller — than the ones Yurie Nagashima had to battle. I believe this is where photography’s emancipatory power has much to offer even for those for whom the camera does not offer that option (in a Western context, this would be heterosexual white men).

After all, true emancipation doesn’t just mean that those confined to a lesser status finally are granted the same rights de facto. True emancipation also means that those who already enjoy those rights come to a deeper understanding what it’s like not to have these rights and to realize the sheer injustice of that. It’s not a zero-sum game.

In other words, while certain members of photoland simply don’t have access to the photography’s emancipatory power, they still can benefit from it if — and only if — they’re willing to have a hard look. You can learn a lot about yourself from seeing another person’s struggle if you realize that you don’t have to deal with that struggle: examine your privilege. Realize that there exists an opportunity for growth, for becoming a better person. Again, it’s not a zero-sum game.

At the same time, the fact that a camera has emancipatory power for some people points at the fact that operating a camera means exerting power, possibly exerting control over someone. We still have to engage with this fact much more critically and deeply in photoland.

In 1996, Japanese art critic Kotaro Iizawa published a book with photographs by Yurie Nagashima and a number of her peers that presented their work as nothing but the kind of shallow photographs girls make (compare this with the kinds of pronouncements you can find in photoland about photography on social media…). If you find yourself objecting to the word “girl”, that’s the critic’s word choice when he labeled the photographs as onnanoko shashin (onnanoko is Japanese for girl(s), shashin is photograph(s)). In light of the preceding it should be clear how insulting this must have been for Nagashima: photographs that were intended as a criticism of a sexist male-centric society were used by a male critic to make a sexist case.

It’s now up to us to do better and to see and appreciate all the power contained in these photographs.

Highly recommended.

Self-Portraits; photographs by Yurie Nagashima; text and conversation with Nagashima by Lesley A. Martin; 172 pages; Dashwood Books; 2020

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.