As is often the case with Japanese photobooks, Shingo Kanagawa‘s A Bright Room comes with a lot of Japanese text (here an essay that spans 26.5 pages) and a very brief English version of it. There is no way that anyone, however gifted they are, can cram those 26.5 pages into one and a half.

Given that my Japanese isn’t remotely advanced enough to read the longer essay, I used the translation app on my phone. But there’s a limit to what such translation can achieve with a language such as Japanese that omits a lot of context (incl. usually pronouns) and where the reading of individual characters can also vary. On their own, the translations of the 27 separate images made some sense; but combined, they did not add up the big picture I had been hoping for.

Long story short (just the facts from the English text), in 2019, Kanagawa started moving in with Aya Momose and Reiji Saito. “We were simply a woman and two men living together,” the English text says, “that Reiji and I got along well with each other; and that we all lived together as friends and equal partners.” Simply — not quite so, as becomes clear from both texts, but in particular from the Japanese one (or rather the fragments I received from my translation app).

I would love to have a full, good translation of the Japanese text. This is not because I need it to understand the photographs; it’s simply that what little I was granted access to has me convinced that in its own right, it would make for very good reading. As it stands, though, I am left with the fragments and, of course, the photographs.

If you’re wondering why I am obsessing over the texts so much, it’s because I started out with the photographs. I always do. When given photographs to look at, I will always ignore the text first, unless it is clear that it is an integral part of the work. Photographers, well Western ones anyway, tend to be rather bad at using text: they always want to explain way too much, and they usually desire to too radically narrow down a viewer’s access to their work (let’s not even get started on the ones that produce International Art English).

My approach is guided by the experience that if a photographer’s work is good, it will withstand the assault produced by bad text. And if it is not good, there’s nothing text can salvage or ruin anyway.

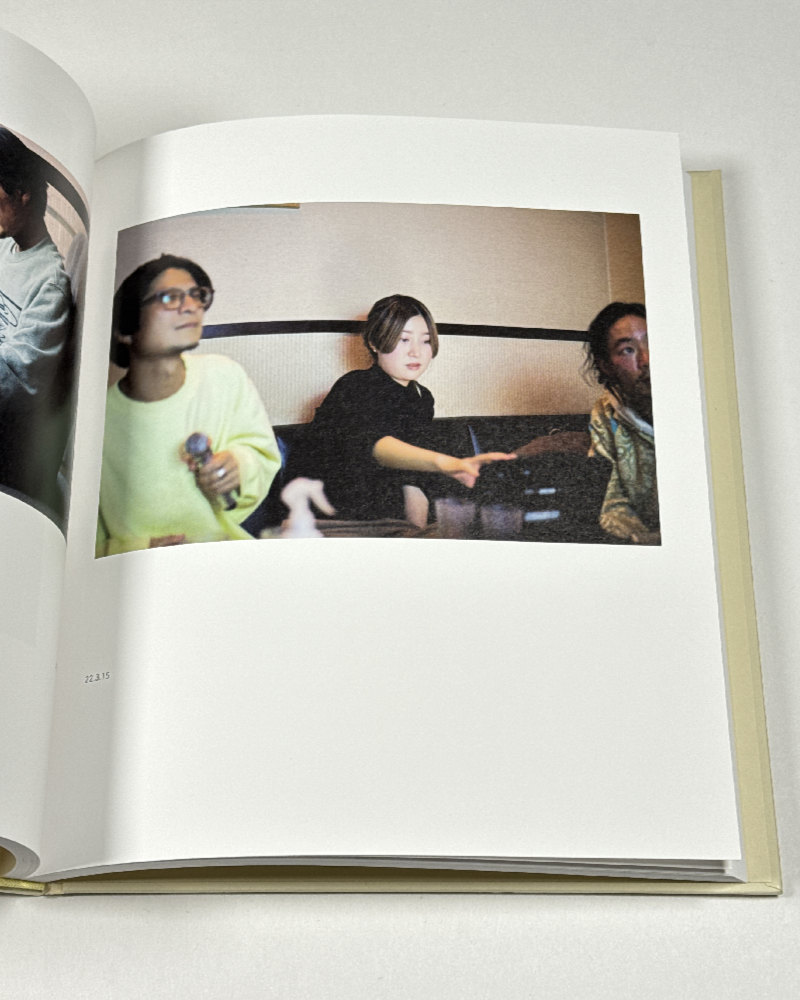

Regardless, in A Bright Room the photographs come first, and they’re sequenced in the order in which they were taken (the dates are listed underneath each one of them). These days, “narrative” is all the rage in photoland. There is none here; but there is so much happening, even though there aren’t really any events taking place.

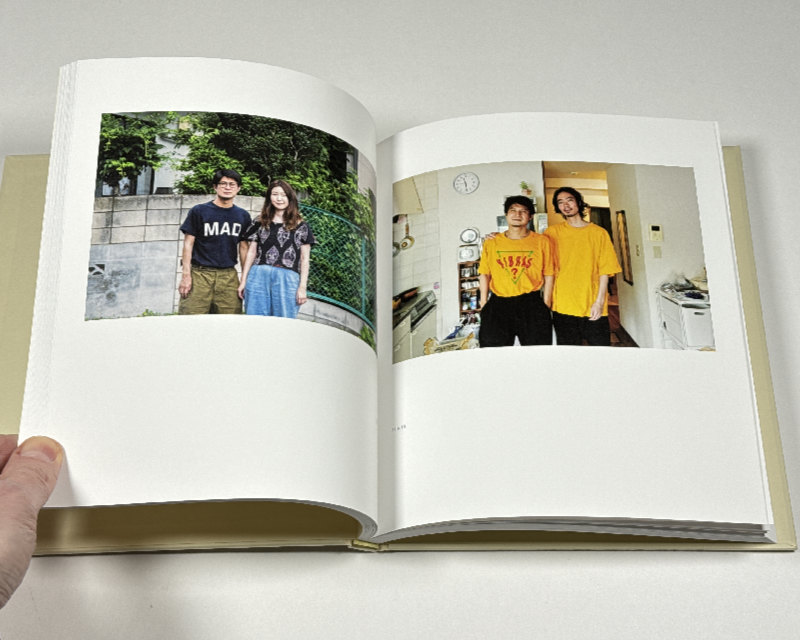

Most of the photographs in the book show either Kanagawa and/or Momose and/or Saito. It’s a rather casual mix of photographic approaches, with snapshots mingling with spontaneous or orchestrated (self-)portraits (and a variety of cameras, including a smartphone). And yet the whole is incredibly coherent in a truly intriguing fashion.

As is always the case with very good photography, the moment the viewer closes the book it asks for it to be revisited: you want to look again. If you maybe want to imagine a contemporary version of Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency that excludes any of the harsher moments from the famous work and only focuses on three people (well, four, at some stage a third man enters the — pardon the pun — picture), you will get a good idea of the emotional weight of the book.

Much like in Goldin’s book, there is an enormous amount of trust, affection, and care between those behind the camera and in front of it. The trust, affection, and care exist between all parties. But you can also see its weight shifting. By that I don’t mean any drastic shifts. It’s just that there are adjustments in the closeness in the three pairs in the constellation.

“I believe the reason I want to be with other people,” Kanagawa writes (in the English text), “is because of a deep loneliness somewhere inside of me. The loneliness I mean is a strong longing to share what I think and feel with another person, an inability to keep these things locked up inside me.” (machine translation of the same quote from the Japanese version of the bookseller’s page about the book produces: “The loneliness I am talking about here is the yearning for someone to receive what I feel and think, rather than just keeping it to myself.”)

Having looked through the book, I had trouble connecting what I saw with loneliness. As someone who knows feelings of loneliness very well, it is certainly not my attention to question the author’s use of the word (さみしさ in the Japanese original). It’s just that in the photographs, I don’t see a lonely person either before or behind the camera.

Instead, I see someone with enormous sensitivity to the weight of human life and to the value of every individual person; again, this had me think of Nan Goldin.

I’m writing these words while there is an all-out assault on both the weight of human life and the value of every individual person by the newly elected government of my adopted home country; a fact that, no doubt, shadows my read of this book.

This is not to say that the book should be seen in this light — it’s a Japanese book after all, and things play out very differently there than in the US (even as in Japan, the rights of same-sex partners are not guaranteed, either).

But for sure, beyond the enormous sensitivity with which Kanagawa has recorded the people he has been living with, despite its very nuanced and quiet voice, A Bright Room very powerfully affirms the rights and value of every human being, regardless of where or how they position themselves in intimate relationships with others.

All of this combines to a masterpiece of a book whose seemingly understated nature reveals deep tenderness and care for the human condition.

If I had just one wish to voice, it would be for someone to produce and publish a translation of the longer Japanese text in the book. I’m longing to read more than merely the disjointed fragments produced by machine translation with its random names and pronouns.

Highly recommended.

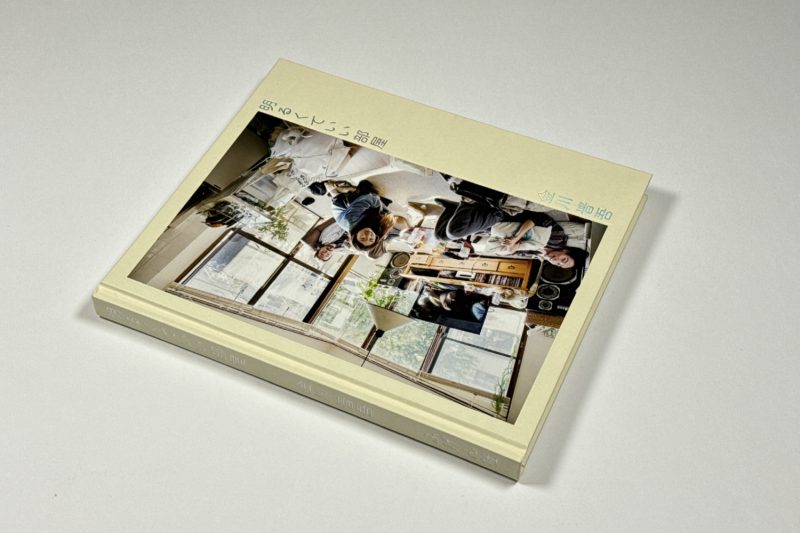

A Bright Room; photographs and text by Shingo Kanagawa; 152 pages; Fugensha; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!