It’s a strange world, isn’t it? On the one hand, we’re fine with being filmed by surveillance cameras all the time, whether by governments or private corporations. On the other hand, we’re usually absolutely not fine with a private individual taking our picture. For me, this is a pretty stunning reversal of the attitude people used to have when I grew up. Then, mass surveillance was one of the worst possible ideas, but few people would complain about some stranger taking a picture of them. I usually don’t belong to people who’ll revert to doe-eyed nostalgia concerning the past. For sure, I would not want to go back to the days I just mentioned. However, I would happily go back to this one particular aspect (just that one, though).

In the world of photography, this reversal has had obvious and often problematic repercussions, especially in the world of street photography. It is probably no secret that I’m not a particular fan of the genre. I feel what little artistic utility it might have had in the past has long exhausted itself. As far as I am concerned any attempt to do street photography today for sure would have to attempt to raise the bar considerably. Of course, that’s true for photography in general, assuming it wants to be art: you will have to ask yourself to what extent and/or how you are raising the bar.

Peter Funch‘s 42nd and Vanderbilt sits at the intersection of Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s Heads, Paul Graham’s The Present, and any classic street photography, let’s say Joel Meyerowitz’s. From diCorcia, it uses the intense focus on a single person even when there are more people in the frame, in other words the way you can use a camera to isolate someone from their surroundings. From Graham, it adopts the idea of multiplicity: two (or more) pictures of the same person in roughly the same location can lead to very different photographic moments. This all brought together and edited smartly resulted in 42nd and Vanderbilt, a selection of street photographs that show the same group of people multiple times.

An index at the book’s end informs us of the precise dates and times when the photographs were taken. For the individual groupings — typically pairs but occasionally three pictures, the resulting intervals fall in the range somewhere between a day up to roughly a month apart. There’s one group in which a pair of pictures was produced within four seconds, and another one where a pair was produced within the same second (there might be more such instances, I didn’t check the whole index). To focus on these times, however, is somewhat besides the point, the reason being that the edit itself does not look as if it had been made with the element of time itself much of a consideration.

Instead, the edit appears to have been made with gestures in mind. For example, if in a pair someone is holding a coffee cup in their right hand, looking down, in that next pictures they will do the same thing. This is interesting. It is interesting because it telegraphs an opinion about those in the pictures. In all likelihood, we would all love to think that we’re unique personalities and that we’re also not entirely predictable. On the other hand, we clearly all have our habits and little ticks. We might pick up that same kind of coffee every morning on our way to work. Most of us also possess a finite wardrobe, meaning that if someone observes us often enough, they will eventually see us wearing the same clothes on different days.

The edit in the book distills these ideas down in such a way that 42nd and Vanderbilt is less about street photography and, instead, about not just surveillance but a particular kind of surveillance, namely one that comes to conclusions. That’s what I meant earlier by “opinion” — someone’s getting at something here. In the afterword, Douglas Coupland mentions the movie Groundhog Day. That’s an interesting reference, albeit one that seems slightly out of place here. After all, in the movie the main character realizes the predicament he is trapped in, and his attempts to escape are shown. But there is no such character here. It’s like a version of the movie Groundhog Day with the main character removed, leaving all the extras behind who do the same stuff day in, day out.

Then again, who says the viewer can’t be the main character? After all, the effect of the book for a lot of viewers clearly must be an eerie realization of how unbelievably tedious life is under late capitalism. OK, so that’s good, albeit not any less obvious than talking about Groundhog Day (Coupland, of course, goes there as well). But in this day and age, one cannot talk about these pictures without taking the photographic aspect itself into consideration. This isn’t 1975 any longer where there aren’t ubiquitous surveillance cameras and where the idea of self-monitoring devices in people’s pockets (that double as telephones) would have been science fiction.

This is where things get interesting, because if Funch is able to record a group of people and then construct something like a critique of late capitalism out of it, what can and will the people do who record us with those other cameras? What do they know? What can they know? What will they infer? What conclusions will they come to — conclusions that might in fact run counter to what we believe in or think is right? In 42nd and Vanderbilt, we find out what is being inferred. With all the other data, though, we usually don’t — unless some whistleblower tells us and then has to live in Russia or in a US prison.

Cameras are tools. The ability to edit a set of photographs to come to a conclusion — that’s a skill. In the hands of fine-art photographers, we’re cool with all of that. We might get offended by someone coming to the wrong conclusion. But what about the wrong hands, the hands of people whose business involves “security” or “business”? Those people largely operate in the dark, and it is that dark that we desperately need to shine some light into. There is a lot more at stake for us than being merely displayed as extras from the movie Groundhog Day.

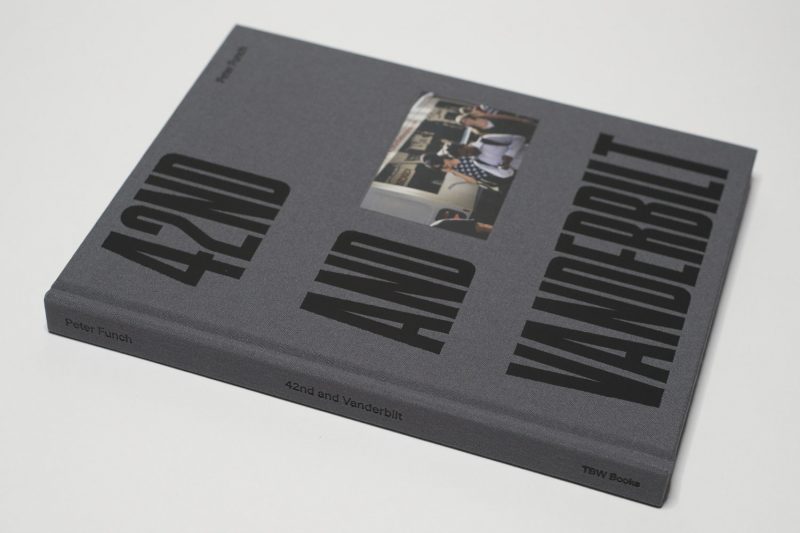

42nd and Vanderbilt; photographs by Peter Funch; essay by Douglas Coupland; 160 pages; TBW Books; 2017

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 4.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.1

Ratings explained here.