Even as there are some fluctuations between the statistics available online, the reality of sexual assault is that it’s very common. “Every 68 seconds another American is sexually assaulted,” the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) reports. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC) writes that “nationwide, 81% of women and 43% of men reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment and/or assault in their lifetime.”

These numbers are US based, and they might differ in other countries. What seems clear, though, is that given the sheer scale of the problem, it’s incredibly unlikely that the US are a strange outlier. Comparisons with other countries can be difficult, though, given the differences in what exactly is treated as sexual assault and what is not (for example, see Why country-to-country comparisons of rape statistics are so difficult).

Given the sheer scale of the problem, you would imagine that more of an effort would be made to combat what easily could be seen as one of the most pressing issues facing contemporary societies. And yet, what we witness instead is a combination of mostly silence and denial.

The lurch to the right/far-right that we’re witnessing for sure is going to make the problem much worse, given that far-right politics has an explicit focus on misogyny and violence (for example: “A jury found Donald Trump liable Tuesday for sexually abusing advice columnist E. Jean Carroll in 1996”).

Furthermore, victims of sexual assault usually have to fight an uphill battle when they step forward. Often, it is them who have the burden of proof; and just as often, in many countries societies will gather around accused perpetrators to effectively shield them from accusations.

The Germans even have a word for that. Strictly speaking, it’s a word that applies to anyone accused of a crime who has not been convicted by a court of law, yet. But funnily enough, Unschuldsvermutung — the presumption of innocence until proven guilty — pops up mostly in discussions around sexual assault. Even if for sure a democratic society should insist on the courts being the ones determining guilt, in cases that almost inevitably start out with someone’s words against someone else’s words, the word Unschuld (innocence) for sure plays a crucial psychological role that creates a systemic disadvantage for those who want to report sexual assault.

As a consequence, a lot of sexual assault goes unreported. The barriers of having to report something very violent and intimate to a group of strangers is already high. The fact that those same strangers then often at least implicitly side with the perpetrators, making the lives of victims incredibly difficult, is of no help. And unfortunately, public opinion is of no help, either. As far as I can tell, most societies will favour siding with those in power over those who have less (or none); and the power always resides with perpetrators of sexual assault.

Consequently, it requires enormous acts of bravery and confidence for victims of sexual assault to come forward and to speak about what happened to them. And then… how do you speak about the unspeakable? How do you convey what has happened to you? How can you express what you need to express?

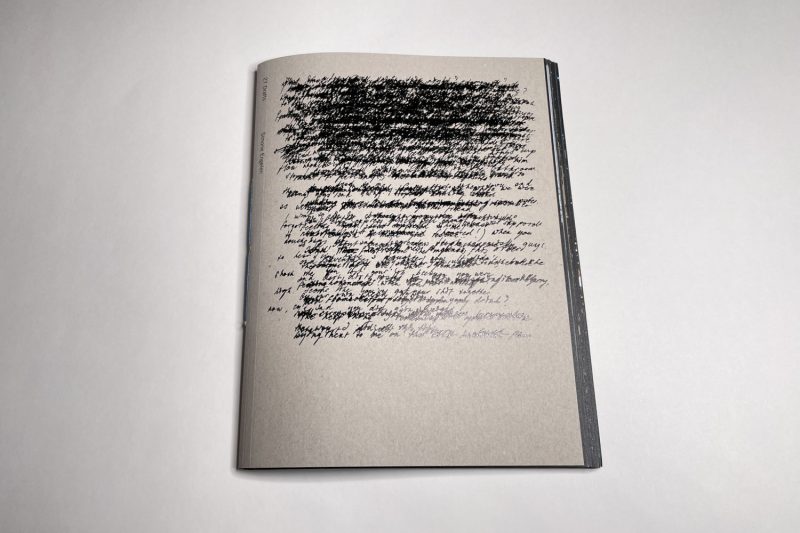

The cover of Simone Engelen‘s 27 Drafts shows a jumble of handwritten lines of text superimposed on top of each other. There is more text at the top than at the bottom, as if someone had started to write something, to then abandon the writing at different points in their endeavour. The cover of the book simply consists of an untreated card stock; the text has been printed in deep black on top. Even though you can literally feel the ink sitting on the paper with your fingertips, I can’t help but think that the words have been burned into the cover.

Crucially, as a viewer you are unable to read the text. The same text reappears later. Strictly speaking, I don’t know whether it’s the exact same text or some other text written by the same person. It’s the same handwriting. And common sense would tell you it’s in fact the same text. The writer and avid reader that I am, I tried reading it. Most of it is illegible, some of it appears to be in Dutch, some in English.

But the idea behind the inclusion of the text, of this text (there’s another piece of text literally inserted into the book in the form of a folded sheet of paper), at least that’s what I came away with, is that you cannot read most of it. What you can read does not add up to much. I think that that’s a wonderful device, even as I can imagine some members of photoland balk at the idea. But bookmaking, good bookmaking, relies on trusting most of your desired audience to get the idea.

I like that idea of trust because in some distant fashion it connects with the trust that needs to exist between the survivors of sexual assault and those who want to be there for them in as supportive a fashion as they can: even where the words might fail to provide the clarity that the latter would prefer (especially given the Greek chorus of Unschuldsvermutung around them), there will have to be the trust that something that might be uncommunicable is in fact being relayed.

With that in mind 27 Drafts is a visual book that conveys its story through the photographs. And that story is simple and clear: to understand it you do not have to have studied photobook making for years.

I could tell you the story, or rather I could tell you how I read the story as it is presented in the book. But I feel that that’s not something I want to do.

To begin with, it’s not a critic’s job to do the reader/viewer’s work. But certainly nobody should feel compelled, for whatever reason, to re-tell the story told by a survivor of sexual assault. The task is to listen. Here: to look. That’s my task as much as anyone else’s.

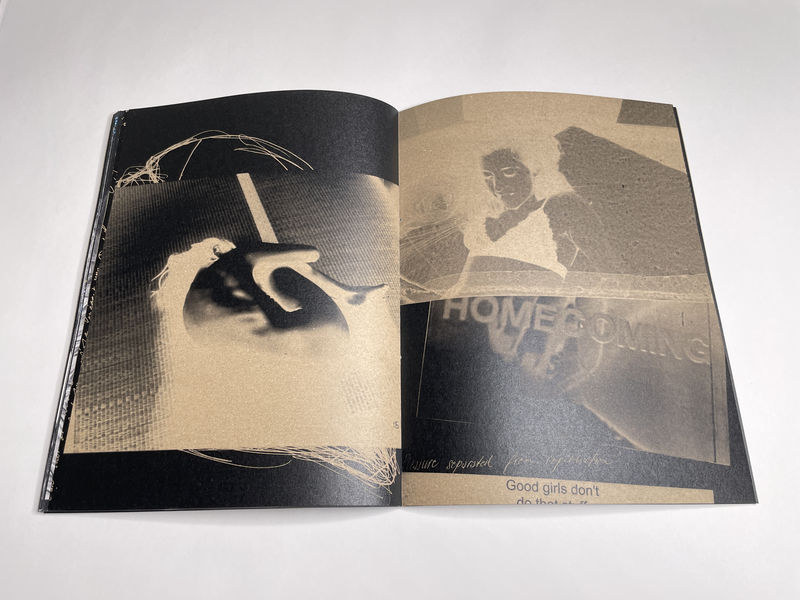

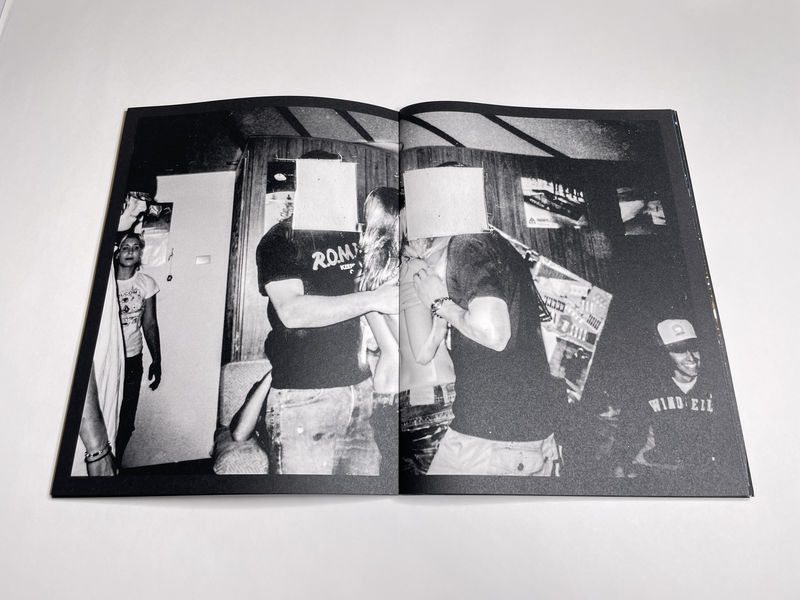

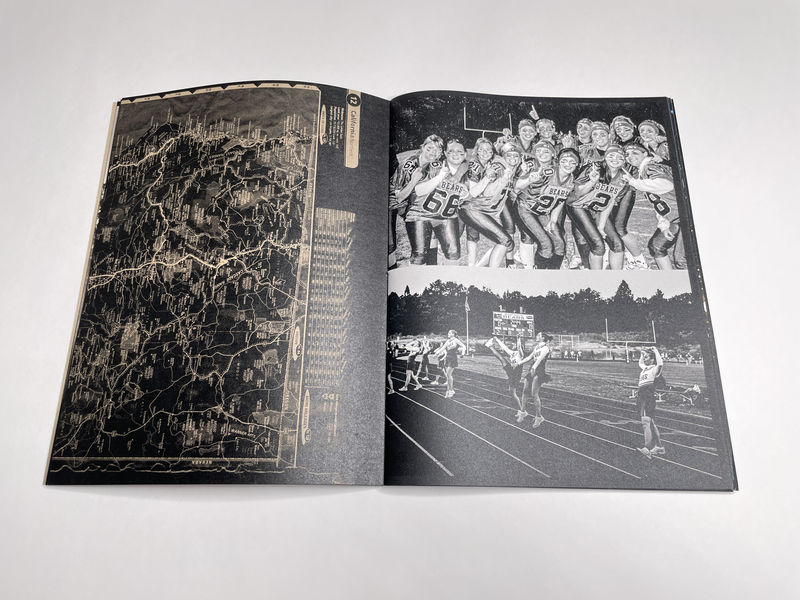

That looking itself if not neutral. This is the second aspect of the book. It centers on sexual assault, but it also centers on what came before and after; and it centers on the conditions under which the assault occurred. It centers on femininity, or rather a type of femininity, and it centers on how that type of femininity can mean very different things for different people — for victims and for perpetrators: rape culture.

When helping photographers to make their books, I always tell them that the most important person they’re making the book for is themselves. Whatever an audience will make of that is outside of their control. If there’s any book where this dictum applies very strongly, it’s 27 Drafts. We have no way of knowing to what extent the making of the book resolved something; and frankly, it’s none of our business.

What is our business as an audience is to find ourselves in the book, meaning: we have to see our position vis-à-viz what is shown here. Again, you don’t want to take this idea too literally (unless you happen to be embedded in some US high-school/college football context in which case: look around, and pick up on all those signs!).

Instead, traces of what can is presented in the book can be found everywhere. It can be found in people’s attitudes towards the way women dress, towards “boys being boys”, towards listening to statements of sexual assault…

It can also be found in the general acceptance of the kind of low-level violence that is par for course in US (and many other countries’) cultures. Just think about how so much entertainment is produced around nerds versus jocks or “popular” versus “unpopular” people.

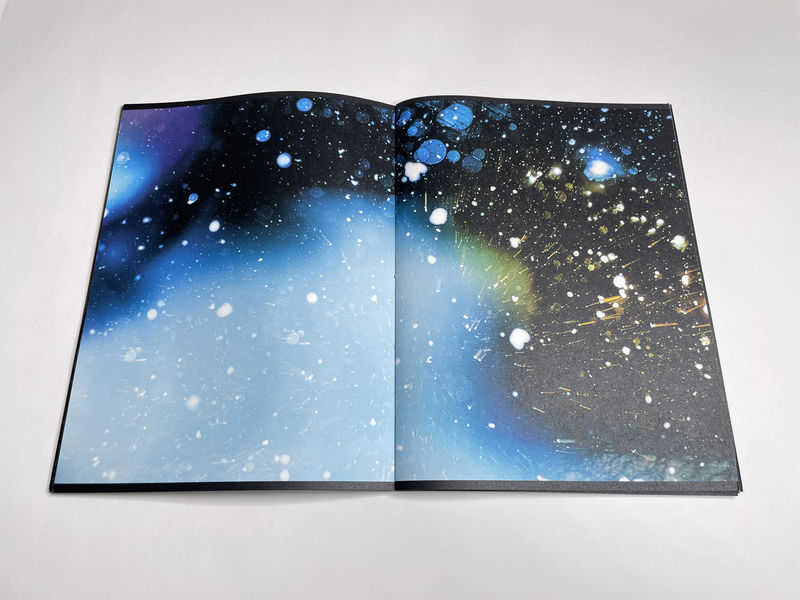

Seen that way, 27 Drafts is akin to a stone that’s being tossed into a lake: the concentric waves caused by its impact move further and further out — until, however faintly, they have touched every part of the water’s surface.

27 Drafts; photographs by Simone Engelen; short text by Anouk Spruit; 108 pages; FW:Books; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!