On 5 February 2024, Helga Paris died at age 85. This had me think that I needed to look at her work again. Rummaging through the boxes of my books, still packed away in an unused room, would not lead me to the desired result: I knew that I did not own a book containing the photographer’s work.

I was aware of a recent book with photographs Paris took at Leipzig’s central train station some time in the 1980s. When it came out, I thought it was OK work but not something I needed in my house. It felt like the kind of work that would resonate in a rather localized fashion: with those who lived in the locale and have some form of attachment to it. This kind of photography is very common. Yo be honest, I usually find it hard to relate to, especially since books tend to lean heavily towards nostalgia.

What I was looking instead was a book with Paris’ portraits. If you look through the website of her archive, I think you will see that that the portraits are the real gems. This is not to say that the other pictures are bad; it’s just that the portraits are simply in a completely different league.

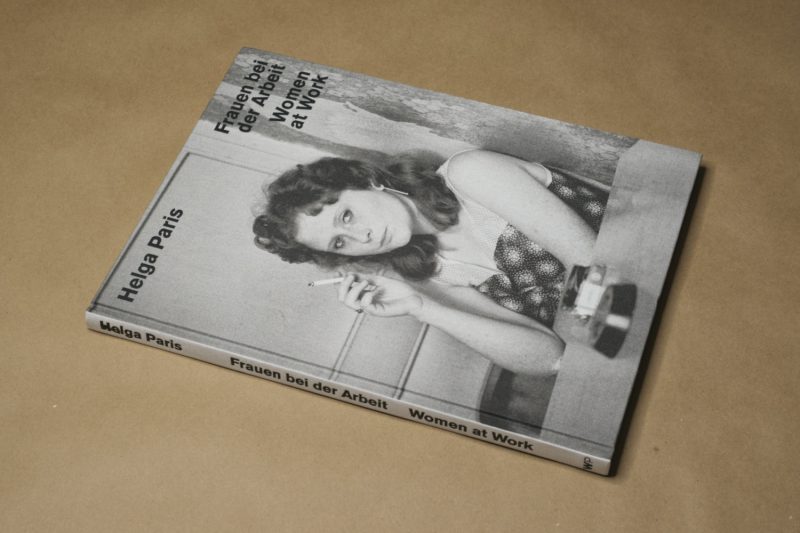

Two years ago, a book entitled Frauen bei der Arbeit (Women at Work) was published. I somehow missed it then, possibly because the publisher was not on my radar (and who has the time and patience to look through DAP’s rather messy catalogue?). I ordered myself a copy.

In many ways, the book is the perfect introduction to the East German photographer for all of those who are looking to add some of her work to their library. It contains a statement by Paris, which describes her interests and how they relate to her life circumstances in a remarkably succinct fashion. And there is an interview with the photographer that further dives into what drove her.

As someone who grew up on the other side of the Berlin Wall, to a large extent East Germany has remained a foreign country to me. For all the right and wrong reasons, East Germans who spent large parts of their lives in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) have not made it easy for outsiders to get access to their world. I don’t necessarily mean this as criticism: being extremely careful with whom you would share private information formed part of their survival strategy. Remember, one in ten East Germans informally worked for the country’s equivalent of the KGB (the infamous Stasi).

And today, it is not easy to talk about that particular past in Germany anyway. If there is anything positive being said or written, inevitably someone (often but not always from the former West) will talk about the Stasi and the dictatorship, and how dare anyone suggest that there might have been positive aspects to any of that?! Subtleties or nuances, you see, aren’t necessarily something Germans do well; and most of today’s societies have become unable to accept the existence of mutually exclusive truths that are present at the same time regardless.

As women in the GDR, Paris notes in the interview, “we demanded equal rights when necessary, and we got them. Did that happen in the West? Probably not. That’s embarrassing.” This obviously is the kind of occasion where the usual suspects would throw in the “what about the dictatorship” bit: The photographer has an important point, and it’s a point that traces through the book, a book made in a Germany where women probably have less rights than Paris and her peers enjoyed in the GDR.

It gets even more interesting if you consider the fact that the photographs in Frauen bei der Arbeit did not have to be made in a clandestine fashion. A lot of East German photographers were unable to showcase their real work because it didn’t conform with state ideology. In its most basic form, though, the photographs of women workers in a garment factory do: the GDR styled itself as the state of workers and farmers, and it is those people whom Helga Paris photographed.

The difference between official GDR photography and Paris’, of course, is that the former had to serve the state. Helga Paris was having none of that. Her interest was in the people in front of her camera. If you read the photographer’s words, she comes across as blunt and unpretentious. It’s exactly the complete lack of pretense that forms the core of what makes these photographs so good and, as I already noted, subversive.

“In photography, you need a certain empathy for the other person,” Paris says in the interview, somewhat casually mentioning what I see as the most important aspect of her (and many of her East German peers’) practice. Even if it seems clear that probably all of the women who found themselves in front of the camera were strangers, the photographer cared a whole lot about each and every one of them — except maybe one who is depicted at a much larger distance, glaring at the photographer.

The following might be a comparison too far for most, but regardless: if you want to ignore the very different circumstances under which and reasons why the pictures were made, I’m reminded of the great Lewis Hine’s child labour photographs. In both cases, the photographers went out to take photographs because they cared for those in front of their cameras — and not only for the resulting pictures. Paris and Hine wanted us to see the persons in front of their cameras and to fully acknowledge them.

There will be blank spots in the history of photography to be filled for at least as long as I’m alive. East Germany still is a rather blank spot (especially outside of Germany), and too many women photographers’ work is also still waiting to be given its due. If you want to add just one book to your library that can do a rather magical job to alleviate part of that problem, it probably should be Helga Paris’ Frauen bei der Arbeit. The fact that it’s a lovely production is an added bonus.

Highly recommended.

Frauen bei der Arbeit/Women at Work; photographs and text by Helga Paris; interview with Oliver Zybok; 120 pages; Weiss Publication; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!