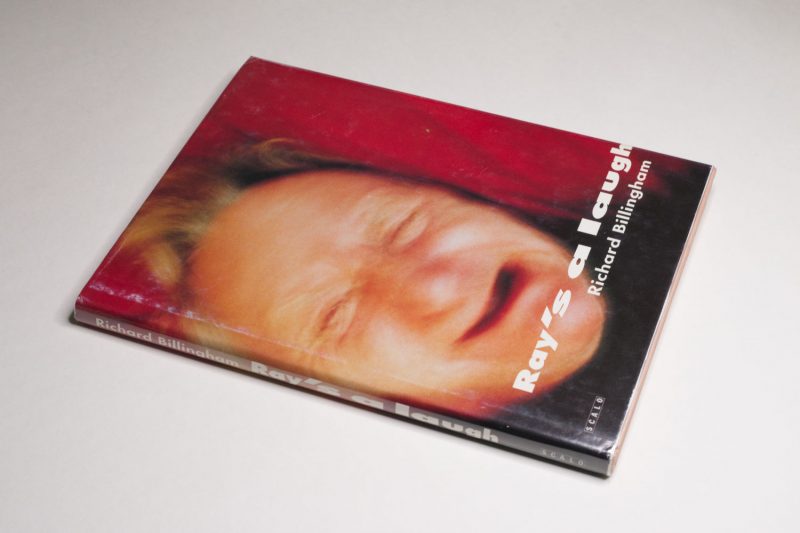

Ray, Richard Billigham’s father, is a laugh — according to the title of the book (Scalo 1996; there’s an early 2024 re-release in modified form by MACK). It says so right on the cover, which shows his blurry face.

÷

Richard’s description of his pictures can be found on the back cover: “This book is about my close family. My father Raymond is a chronic alcoholic. He doesn’t like going outside and mostly drinks homebrew. My mother Elizabeth hardly drinks but she does smoke a lot. She likes pets and things that are decorative. They married in 1970 and I was born soon after. My younger brother Jason was taken into care when he was 11 but is now back with Ray and Liz again. Recently he became a father. Ray says Jason is unruly. Jason says Ray’s a laugh but doesn’t want to be like him.”

÷

So it was Jason, Richard’s brother, who said that Ray was a laugh. It’s a jarring title once you start looking at the photographs.

÷

From 1949 until 1961, there existed a radio show on the BBC entitled Ray’s a Laugh. The star of the show was comedian Ted Ray. Ray (the comedian) was billed as a laugh. I would have to ask someone in Britain, in particular someone who experienced the mid-1990s, to find out whether the show would still have been known over three decades after it ended. Maybe it was just a convenient enough title for the book. Regardless, now Ray, the father, is a laugh.

÷

I felt squeamish about the cruelty in Masahisa Fukase’s Kazoku. Richard’s photographs do not leave me unaffected, either. In Fukase’s case, I have severe misgivings about the cruelty and about openly making a mockery of the family using carefully staged studio photographs. Billingham’s pictures, in contrast, are taken from real life using cheap snapshot cameras. I wouldn’t know this for a fact, but I’m pretty certain that Richard did not ask his alcoholic father to sit on the floor next to a grimy toilet bowl. He saw the scene and took the picture. That’s a different kind of cruelty than Fukase’s.

÷

I don’t want to be slicing and dicing ideas of cruelty here, but I needed to point that out.

÷

Maybe when I said that Billingham and Fukase employed different kinds of cruelty, what I really meant was that their cruelty manifested in different ways. After all, in his book Memories of Father, Fukase mostly photographed the way Billingham did.

÷

As I said, from the photograph I have no way of knowing whether Billingham found his father sitting next to the toilet. I have no reason to believe that that’s not what happened. In the other photographs, frequent drinking is on view. Ray was an alcoholic.

÷

Alcoholism — now called Alcohol Use Disorder — might look and act out like a social disorder, but it’s not. It’s a disorder that requires medical attention.

÷

Much like Fukase presenting his frail, ailing old father like prey in front of a studio camera, Billingham’s snapshot of Ray does nothing to enhance the older man’s dignity but everything to lower it. Ray has hit rock bottom. It would seem that he hit rock bottom a long time ago, and there no way out.

÷

Why do I need to look at Billingham’s photographs of Ray? I have been entranced by the book ever since I first saw it. For a while, it was not easy to come by. Originally published in the 1990s, it had been out of print. It took me years to find a used copy that cost not much more than my spending limit of $100 for single books. Until the book arrived, I had seen it only in reproduction. The thrill of being able to see the actual book was immense, and I was immediately in awe of the visceral power of most of the photographs. At the same time, I also found myself even very conflicted by my admiration of these very good photographs of often very terrible scenes of domestic squalor and neglect with their strong undercurrent of emotional violence.

÷

“When you’re taking photos, put yourself in the position of the weakest.” Kazuo Kitai remembers that he received this piece of as advice from Ihei Kimura, one of the widely acknowledged and admired masters of Japanese photography.

÷

Just now, I realise that Fukase and Billingham might have seen themselves as being in the position of the weakest person. After all, they were the sons who had to deal with being their father’s offsprings. Fukase remembered in the afterword of Kazoku:“I was terrified of my father as a child. He had an extremely short temper, and he would fly into rages at the slightest thing.”

÷

Even as a camera gives you considerable power — you literally get to shape how other people will be seen, it is very difficult for many photographers to be mindful of it, in particular when being confronted with the power a father figure seems to exert (even if in reality that power might have now waned if not outright disappeared).

÷

As viewers, we pick up on being confronted with a person that Kimura would have described as the weakest. Or maybe we pick up on what a photographer decided to do with such a situation. Photography has a funny way of muddying these waters. In the case of Fukase’s and Billingham’s pictures, I’m finding myself siding with the vulnerable fathers. I’m finding myself admonishing the sons for their photographic choices.

÷

There’s a problem: I’m taking a side. Kimura’s advice might be good and useful when a photographer takes pictures of strangers. But in a family setting, things become infinitely more complicated: the photographer is part of the family. In the case of the sons, it was them who were first subjected to their fathers’ whims, however much or little those fathers were aware of what they were doing. The sons’ hurt is real, and it came before any of the pictures were taken. There is a cause-and-effect relationship that connects the hurt and the pictures. That relationship can never be disentangled in a satisfying manner. Thus by taking a side, even as (I think) I mean well and regardless of how spontaneous that act might be, I’m pretending (or hoping) that as an outsider I am able to disentangle a very complex situation.

÷

Ray’s alcoholism was an illness. But explanations aren’t excuses. In any case how would one go about connecting them? Could Ray’s alcoholism serve as an excuse for the situation his wife and sons ended up in? The brokenness of the alcoholic man’s life must not get in the way of trying to understand the brokenness of his partner’s and descendants’ lives.

÷

“Something I’ve come to realise,” Joanna Cresswell tells me in an email, “is that blame is sometimes unlocatable. In general, the only part I struggle with is the idea of any ‘sides’… All I really see is people hurting each other in human ways.”

÷

Hurting each other in human ways.

÷

Now, I realise that while I take sides, I also find myself wanting to differentiate between Sukezo Fukase and Ray Billingham, the two fathers, or rather the situations they found themselves in, when they faced their sons’ cameras. Sukezo’s old age simply was a part of life itself, whereas Ray’s alcoholism was an illness. I feel sorry for both of them, but in different ways.

÷

“But pity is an ugly emotion to stomach,” Joanna continues, “and perhaps pity in itself can be cruel.”

÷

Joanna’s words helped me see how conveniently easy it was for me to write that I would have wished for more forgiveness from these sons photographing their fathers. I have no emotional attachment to any of those families. I only have what is being created by and through the photographs I’m looking at. Consequently, I have to be honest with myself. If I demand more forgiveness from these sons photographing their fathers, then I have to demand the same amount of forgiveness from myself when I think about my own father. I am not better or more virtuous than these sons. We all just ran away when we could. But they went back with their cameras to take pictures. I never did. Instead, up until I made myself write down these words I preferred not to deal with anything.

÷

Now, I’m writing about other people’s fathers and pictures and hurt as if somehow I were able to pick things apart from afar and with the added hindsight of time having passed.

÷

What am I even doing here?

÷

“My father. Where to begin?” asks Joanna.

÷

My father. Where to begin?

÷

As I noted, my reaction to Billingham’s work of Ray is made more complicated by the sheer fact that despite their raw, gritty nature, the photographs are so compelling. There is a photograph of Ray throwing the cat. Sitting in a fold-out beach chair in his living room, the camera has caught Ray right after the cat went flying. In the picture, the animal appears to be levitating above him, harshly illuminated by the flash of the camera but not in any visible distress. The photograph possesses all the short drama of life, while capturing it in the best possible way. It looks like a snapshot, and yet it also is the perfect snapshot — the lucky moment when everything aligns as if it had been carefully laid out that way. Everything is in just the right spot.

÷

(I need to believe that it was a lucky shot and not the result of repeated throwing for the sake of a picture.)

÷

You could see the casual performance of a minor act of cruelty towards an animal that was caught in this picture as proof that Ray was indeed a laugh. It’s easy to imagine one of the sons having a beer in a pub with his mates, retelling the story, and sharing a laugh. I will have to admit, though, that even as I like the picture very much, I don’t see the act caught in it as evidence of Ray being a laugh. Instead, I feel repelled by the man or rather by the kind of man he was in that moment. Cruelty towards animals, even the seemingly inconsequential kind, is not funny.

÷

Looking and re-looking at all of these photographs, again and again I’m asking myself how I can cast judgment on these photographers/sons and their decisions what to do and what not to do. There is, after all, what I do and mostly not do while dealing with my own father. I am unable to say that I am particularly proud of being very curt in the occasional brief exchanges with him. But I am also unable to say that I am making an attempt to change the dynamic.

÷

I used to think that for a situation between two people to change, it would have to be up to both – and not just to one – to own up to their respective behaviour that had them end up where they are. Now, I’m not so sure any longer. Or rather, I have come to realise that there is one person whose behaviour I can change, and that person is me. Even if the situation will not change, I now know that bearing a grudge does nothing for my own personal good.

÷

Secure your own oxygen mask first, they tell you during the safety instructions on an airplane, before helping others.

÷

For now, the photographs I am looking at here aren’t bringing me much closer to what I want to figure out.

÷

There is the added complication that photographs tempt the viewer to offload all their judgment onto those involved, whether the persons in the pictures or the photographers who took them. This mechanism is particularly pronounced in the case of photographs of atrocities or similar extreme situations. For example, in 1993, Kevin Carter took a photograph of a young child in (now South) Sudan who was trying to reach a United Nations feeding centre. The child looks terribly starved. Hunched over all on all fours, his head low to the ground, the scene is terrible enough, were it not for the presence of a vulture that sits nearby, eyeing the possible prey. After the photograph was published in the New York Times, the newspaper was compelled to publish a special editorial. It addressed some of the questions it had been made to face. “Many readers have asked about the fate of the girl. The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the center.” Much later, in 2011, it was revealed that the child actually had been a boy named Kong Nyong and that he had been taken care of. In 1994, the photograph won a Pulitzer Prize. A fierce discussion over the photograph erupted: was it right to take these kinds of pictures? Was this not, and yes, that is the term used, “poverty porn”, the photographic glorification of poverty? Four months after being awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Carter took his own life. Even if his photograph has nothing to do with the ones I have been look at here, all of these pictures have arisen from someone making the decision to take them. As outside viewers, we have no way of knowing what else happened in the particular situation. Photographs reduce the complexity of life (and death) down to the few traces captured in them. And as viewers, we find ourselves tempted to conclude that that’s all there was, that Billingham found Ray next to the toilet, took a picture, and walked away or that Carter found a vulture sitting next to Kong Nyong, took a picture, and walked away. We don’t really know that. Carter later revealed that he had chased the culture away. But for us viewers, we only have the pictures, which means the fact that they were taken and the facts that they visually reveal (or that we think that they reveal). I have looked at and written about photographs for a long time now. Still, I find myself making this same shortcut to what I believe to be a valid conclusion again and again.

÷

The violence of an image always shortcuts our critical thinking, at least initially. The violent facts depicted in it take precedence over everything else. If we’re not careful, they will drive us to the wrong conclusions.

÷

I envy Joanna who writes that “Billingham’s pictures broke my heart. They aren’t beautiful, and I still wince a little when I look at them, but I love them because they showed me a form of acceptance and creative redemption I had never seen before.” I wish I could see the form of acceptance she is able to see.

÷

Joanna also writes: “We are the ugly parts of ourselves as much as the polished ones.” What then am I having problems with in Billingham’s pictures? Is it the fact that he is airing out a laundry that part of me feels shouldn’t be made to be seen? Or is it the fact that these pictures remind me too much of the ugly parts of myself?

÷

Maybe it is the fact that unlike Joanna, I don’t allow the work to break my own heart?

÷

In other words, am I attempting to reason myself out of my corner by approaching all of these pictures as a critic — and not as a son? (As if it were possible to separate the two.)

÷

Richard re-created the family life depicted in his book in the form of a movie entitled Ray & Liz (2018). The internet movie site IMDB describes the film as follows: “Photographer Richard Billingham returns to the squalid council flat outside of Birmingham where he and his brother were raised, in a confrontation and reconciliation with parents Ray and Liz.” It’s easy to see how making the movie is a form of confrontation, a confrontation with facts, though, less with people, namely the facts of his life as a child and adolescent. The reconciliation aspect might be present through the act of making the movie itself — and not so much through anything shown in it.

÷

Whatever might be the case, it’s this aspect that is holding me back when dealing (or rather not dealing) with my own parents. I am still working on mentally reconciling the facts of my own upbringing with what I wish they should have been. Obviously, there is no way that reconciliation can ever happen until I fully accept that differences sometimes cannot and need not be overcome and that living with differences is possible. Mentally, now that I’m firmly into the sixth decade of my life, I have understood that this is the case. Emotionally, I’m not quite there, yet.

÷

“With the photographs I tried to make them as truthful as I could and hopefully that element overcomes any exploitative element,” Richard is quoted as saying in a long article about the movie that appeared in The Guardian two years before it was released. “I think there was a warmth to them.” I’ve looked at the photographs many times. I’m unable to pick up on that warmth.

÷

Often, we see in pictures not what they show but rather what we want to see.

÷

“I just hated growing up in that tower block,” Billingham said. “I didn’t like being unable to walk out of the door. You had to get in the lift and people would piss and shit in the lift and spit on the walls. You had to be careful never to lean on anything.” Even as the pictures don’t show the lift, I can see his visceral dislike of the living conditions in the pictures.

÷

Once Ray & Liz had been released to some acclaim, there was another article in The Guardian. “Up until their premature deaths about a decade later,” Tim Adams writes, “Billingham’s parents were mostly oblivious to the fact that they had generated a Turner prize nomination and global gallery fame.” I might as well ask how the parents could have possibly understood what the Turner prize means or how galleries operate (and who frequents them). I’m thinking, though, that they might have had feelings about mostly well-off people looking at the circumstances of their living and about the open depiction of Ray’s alcoholism. Of course, the moment you make art based on your own and your nearest relatives’ personal lives, there is the simple fact that a lot of strangers might not only see it but come to their own conclusions.

÷

“We are walking upon eggs,” T.P. Thompson wrote in 1859, “the omelet will not be made without the breaking of some.”

÷

“Jason [the brother] often says to me now that, statistically, we should either be in prison or dead or homeless,” Billingham tells Tim Adams.

÷

A life lived, whether it’s one’s own or somebody else’s, is too complex for anyone to arrive at simple conclusions. “Well, I had to look after myself, I suppose,” Billingham says,“[a]nd it’s the parents’ job, isn’t it, to look after the little one?” Yes, it is, even if, as appears to have been the case here and in much different circumstances in my own upbringing, the parents are incapable of doing it in a way that the children later deem adequate.

÷

I suppose it comes down to the following. It’s one thing to try to hold your parents accountable when you feel that they were insufficiently attentive to your needs when you were a child. Probably a lot of children have that feeling about their parents. There might have been material shortcomings or emotional ones, the latter maybe in the form of a lack of support. Who knows. But it’s quite another thing to make that the subject of your art when it is then supposed to go out into the world. At least that’s the thought I come back to time and again, possibly also in part because in the society I grew up in, private problems are not supposed to be aired out in public.

÷

Whenever being confronted with a piece of art that challenges a person, I always consider whether an artist is punching up or down. This idea introduces some relativity into my ethics of looking, a relativity that first and foremost challenges me: why would it be OK to punch in this case, when it’s not OK in that other case? Inevitably, coming to a conclusion will still leave me somewhat unsatisfied, given that I mind the fact of the punching, regardless of where it happens. Still, in the context of art, there also are the wider circumstances in which it is happening, which here means galleries or museums often frequented only by the well off, or expensive art books made for that same audience. There is an inherent violence to this aspect of class that the world of art typically prefers not to discuss. There is violence in well-off people looking at photographs of other, radically less well-off people. I find it difficult to justify exposing those who have less and who in general are also very much aware of that fact to the eyes of those who have a lot more. And it is this particular aspect that bothers me in the case of Richard’s photographs of Ray and Liz, even if I cannot and will not deny that his own coming to terms with the very situation depicted in them is important for him. After all, you could say the same thing about all of these words. So maybe my being conflicted here simply reflects that fact that the further I proceed in this investigation, the more I find myself challenging this endeavour. But I must proceed, not only because it’s possible that I am very wrong about all of this. It’s also possible that pushing through what right now looks like a solid wall might actually teach me more than I am able to imagine right now.

The above is a slightly edited excerpt from the manuscript of my unpublished book Memories of Fathers.