The main problem with the neoliberal photography museum — such as Fotografiska — is not that it doesn’t treat photography or photographers properly. To insist on such proper treatment is to miss the place’s mission entirely: what is on view is not photography. Instead, it is neoliberal capitalism itself as it manifests itself through a combination of consumption and of a proper mindset. The photographs on view are merely ornaments.

I should note that we’re stuck with a bad term — museum — that has us evaluate one locale against another. The are many glaring problems at a number of museums. The Whitney Museum board included a producer of tear gas, MoMA has ties to fossil fuel, the British Museum (and many others) is filled with looted goods.

So the fact that Fotografiska isn’t a museum in some ways (the way it is dealing with photography) but very much a museum in other ways (the unseemly control wealthy people control what is on view) tells us that to focus on the what a place might have to do to be called a museum is a grave mistake.

To begin with, though, the idea that you can’t have a museum without a collection is ludicrous. It only serves to preserve the power of existing museums. It’s also self-defeating, since many museums don’t have the purchasing power to operate in the contemporary art market.

In the end, what matters is the quality of exhibitions put on display. This includes not only curating in the narrow sense of assembling something under a theme (“Nudes made by female artists”) but also creating a solid framework around it that intends to enrich the audience’s understanding with wall text or multimedia presentations or simply old-fashioned catalogues.

In 1971, Hans Haacke was supposed to have an exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York City. Haacke wanted to include a piece about real estate: “The works contain no evaluative comment. One set of holdings are mainly slum-located properties owned by a group of people related by family and business ties. The other system is the extensive real estate interests, largely in commercial properties, held by two partners.” It was not to be. The show was cancelled, the curator in charge was fired. (You can find Haacke’s words in the article.)

The 1971 Haacke incident obviously has nothing to do with Fotografiska Berlin. But it actually has everything to do with it. To understand this better we need to understand that the neoliberal museum serves more than one function. A minor and relatively unimportant part of the functions is to showcase photography (regardless of whether the staff are actually aware of this or not).

The main function is something different: it’s commercial. Fotografiska Berlin is part of a real-estate development in Berlin that is geared towards the very wealthy. The museum’s role is to serve as an ornament, as a token. It provides a veneer of culture in an environment that otherwise is devoid of it. Not every neoliberal museum is attached to an effort to zhuzh up real estate, though. But you want to always see whether there might not be some other purpose when another one of these places opens somewhere.

Neoliberal capitalism will happily appropriate anything and use it for its own goals (well, almost anything, I’ll get to that). And art in general provides a brilliant opportunity to kill a number of birds with a single stone: you can invest in art (satisfying your financial needs). But through that investment you can also buy cultural and societal cachet, and you can showcase how much you care or pretend to care about larger societal themes (such as diversity or feminism or whatever else).

If you think about it, that’s brilliant. What else can you buy that delivers such a broad return on investment? If you look at things from this angle, traditional museums are not necessarily exempt from the criticism I’m leveling here. As I already noted, the boards of many museums are filled with people who view their presence as a commercial investment and who will use their influence accordingly.

We need to be talking about all of these institutions in general — even as some might be a lot worse — or maybe blatant would be the right word — than others.

By the way, none of the above or of what is still to follow is intended as a criticism of the photographers who for some reason or other agree to have their work shown at these places. Theirs is the world of precarity that the people behind these institutions exploit. Specifically, the Berlin based artists exhibiting at the local Fotografiska are part of the many Berliners who have trouble finding or keeping affordable living spaces. In addition, they might struggle having or finding affordable studio spaces.

Fotografiska isn’t any more dedicated to photography than Pier 24 was. Founded by a wealthy venture capitalist, for a while Pier 24 upended the United States’ photography scene in general and San Francisco’s in particular, establishing itself as a locale where photography was going to be celebrated (never mind the insanely elitist way photographs were supposed to be viewed). This went well until the city stepped in and demanded a fair rental contract for the prime location in question. It was at that stage that it was announced that the collection was going to be auctioned off, with Pier 24 closing down.

Given that previously, the site’s focus and dedication to photography had been talked about so much, the obvious question is how much dedication there had been in the first place. I know that its staff very much care for photography (I’ve spoken with a number of them, and I admire their dedication to the medium). The photographs could have gone to local museums, or some other locale could have probably been found. But for its owner, Pier 24 might just have never really been about photography in the first place.

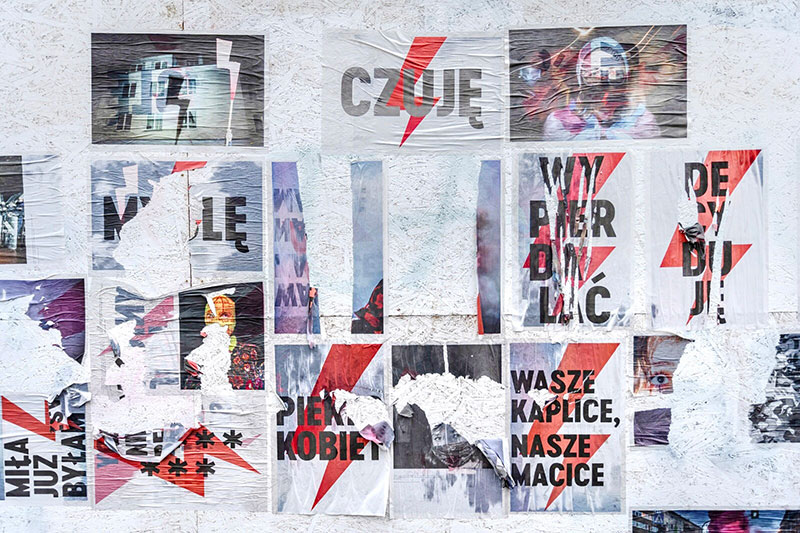

The interior of the Berlin Fotografiska, based in Berlin’s Mitte district, a completely gentrified hellhole of shallow consumption, features graffiti made by squatters who occupied the building until they were evicted. Given that the graffiti is legally protected (as noted by Berlin based newspaper taz), removing it would not have been an option. But gentrifiers love graffiti because it confers a sense of edgy credibility.

A lot of appropriation is obscene, but this one is particularly so. Visitors pay good money so that the new owners of an old building show them how adornments made by people hoping for a more just and equal society now serve to demonstrate how the state (city) conspired with capital to defeat what both saw as a threat to their dominance.

There’s a telling quote in a recent New York Times article about Berlin’s Fotografiska. “What’s happening in Berlin is, we had a great time drinking out of plastic cups,” Yoram Roth, the person behind the place, is quoted as saying, “But we have an audience now that wants a nice glass of wine, a sensible meal, and to be part of the cultural landscape.” That “we” in the first part — that’s the revealing bit. That “we” includes Roth and his peers: wealthy individuals, property developers, bankers, people who inherited money — the Mitte district crowd. And that “we” has now decided that it would rather swap out those who can’t be too picky about their drinking receptacles of choice for those who can. So it goes.

It’s the old story of gentrification: artists occupy run-down spaces, create a cool — if edgy — atmosphere, and rich vultures buy them all up and transform them into a “cool” shopping centers. And finally the well-off can finally enjoy “a nice glass of wine” and “a sensible meal” without having to worry about the creative underclass and their uncouth ways of living any — even as, of course, they keep their adornments for show.

Of course, it would really not be the New York Times if the article did not include gems such as the following: “Although their models might be different, there is some overlap between the Tacheles’s objectives and those of Fotografiska Berlin”. Someone from Fotografiska gets to explain why that is (I guess cribbing from the place’s PR notes would have been too obvious?). The article’s final line gives away whose perspective you’re reading: “In the meantime, maybe Berlin will finally offer a decent martini.” The New York Times writes for the “we” crowd.

I already noted that the neoliberal photography museum is not interested in photography. It is also not particularly interested in photographers. If there is support for photographers, that support is merely a side effect of the larger endeavour. Of course, at this stage the world of art photography is so starved of meaningful financial support that the moment someone steps in to offer anything, that will be seen as an incredible improvement.

However, I maintain that any initiative that does not address the systemically starved support system of photography is not interested in helping photographers — even if selected individuals might indeed rake in some money. Any initiative that does not engage and cooperate with already existing local photography institutions or museums is not interested in furthering photography in the particular city it appears.

What makes this all more complicated is the fact that the people behind Fotografiska are diverse. This should be the lowest of all bars but, alas, in Germany certainly isn’t. For example, over the past few years the main exhibitions at C/O Berlin have been dominated by very old (mostly white) men, many of them from the US. That’s just really, really bad.

However, even as the neoliberal museum and its patrons will indeed express a keen interest in societal issues, maybe even embracing intersectionality (the fact that individual topics should not be seen in isolation from each other), such intersectionality always excludes money and class. In 1971, the Guggenheim did not want to talk about money and class. Today’s neoliberal museums don’t want to discuss these, and neither do the denizens of Berlin’s Mitte or Prenzlauer Berg districts. This mirrors larger parts of the art world that has made itself dependent on capital.

We might note that historically, the arts have always been closely enmeshed with powerful wealthy people who threw artists some crumbs to further their own interests. I suppose for me it’s fascinating that I am able to observe in real time what I previously read about in history books, with contemporary Andrew Carnegie types throwing around a little money to whitewash their name while furthering their businesses.

What ended up driving me to write this article was not the emergence of yet another Fotografiska, the one in Berlin. Instead, it was the way Pier 24 folded after it was unable to extend its lease with the city. Deciding to close it all down and to sell off the collections — that struck me as such a temper tantrum. Who does that? Who builds up a pretty amazing collection of photography, talking about their love for photography — only to then just dump it?

And then I realized the type of person behind it: someone who has interests other than photography in mind. It’s pure neoliberal capitalism: if something doesn’t work, destroy it and move on to the next thing (regardless of who or what falls by the wayside). If something needs a little whitewashing — let’s say the gruesome gentrification of Berlin’s Mitte district into a neoliberal Disneyland — then let’s add on a little museum that ticks a few important boxes.

In 2020, Art in American described Fotografiska as one of the “virtue-signaling institutions”, and that seems about right. That is neoliberal capitalism as well: exploiting the planet and then sipping the wine (mind you, out of real glasses!) in front of art that, you see, is critical.

The difference between, say, MoMA and Fotografiska Berlin might come down to the following. The former is a museum that comes with a gift shop. The latter is a gift shop that comes with a museum. Both are controlled by wealthy people with very specific interests that are defined not by what is included in its spaces but what is excluded. Whether one is really so much better than the other is absolutely not clear to me.

Where this leaves photographers also is not clear to me. In a nutshell, as photographers we are in desperate need of a much larger and much more robust support system. We’re not going to get it from politicians, and for sure we’re not going to get it from the people who fund neoliberal museums.

So how can you go about what you want to do?

Obviously, individual photographers will have to make decisions for themselves. Like I said, I don’t have a problem with photographers working with neoliberal museums. If it makes you money or gets your work in front of an audience you think you want, that’s great. Just don’t forget about the larger picture.

What it comes down to, though, might be something a friend told me the other day. Museums might simply be comparable to malls: relics of the past that are failing. The question is what might replace them.

Given that many photographers share the same struggles, cooperatives or similar structures might provide a good way to create mutual support systems. Creating and working in a shared exhibition space also might be much easier if you can share resources and skills.

Given the troubled real-estate situation in places like Berlin, such spaces might simply be temporary. But temporary spaces might be able to re-produce some of the exciting and creative atmosphere that neither traditional nor neoliberal museums can offer.

For this to work, artists will have to consider their own needs much more than they do when they make themselves dependent on the trickle-down support offered by the wealthy.

They also need to reconsider who their audience actually is — or whether they really want to make art only for other artists, for curators, and for the occasional rich person who waltzes in to pick up another investment.