Ordinarily, I would have simply introduced my conversation with Rob Hornstra with his history as a photographer, most notably his work with writer Arnold van Bruggen in the Caucasus: The Sochi Project. That work entailed a large number of highly successful self-published photobooks, all of them crowdfunded at a time when such an approach was only beginning to become more widely used. It ended up getting the pair being banned from Russia. There now is a new project, The Europeans, which follows similar ideas in a different setting.

But since 24th February 2022, The Sochi Project has taken on a completely new meaning and relevance, given Putin’s attack on Ukraine has brought the brutish Russian conduct in the Caucasus with its massive human-rights violations and innumerous war crimes right into the heart of Europe (Europeans had conveniently ignored them when Russia bombed hospitals in Syria and reduced entire cities to ashes).

The following conversation was conducted three weeks before the start of the war in Ukraine and for that reason does not include a discussion of it. It has been edited for clarity and length.

After the start of the war, Rob made copies of the book An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus available for sale, with all proceeds going to the Ukrainian Red Cross: “After previously selling 84 books within a week, our stock was exhausted. We donated 3,990 Euros to the Red Cross. Now our publisher Aperture has decided to supply new stock free of charge. Brilliant! The action continues! For every sold book we donate 47.50 euro to the Ukrainian Red Cross.” If you’re interested in a copy follow this link.

Jörg Colberg

The last time we spoke your partner and you had just had your first child, and you were teaching. You had also finished The Sochi Project, a massive project with crowdfunding and a lot of trips. With time passed now, looking back — how do you see that work?

Rob Hornstra

What we achieved — Arnold van Bruggen and I — is more than we expected when we started the project in 2009. Especially around the Olympic Winter Games and the months before, when we got banned from Russia, that’s when we had a tremendous number of articles and media coverage. I think the project truly managed to make an impact by shining a different light on the Olympic propaganda machine of the Russian regime. It was bigger than we ever expected. So the whole project itself… I’m still satisfied.

If you interview athletes before, let’s say, the Olympic Winter Games in Beijing they all say “it doesn’t matter if I win a gold medal, but I need to have the feeling that I did the best race of my life.” I feel that in those five years we did the best race possible. We couldn’t have done more especially when you consider the very limited financial resources we were working with. More exhibitions, more sold books, more articles, more than we expected. I don’t feel that we could have gotten more out of it.

JC

I think at the time, and even now looking back, it was a cutting-edge way to work with photography and also an attempt to engage with an audience in ways that went beyond the usual ideas: here’s a photobook at a book fair that only photographers go to, here’s a gallery show. You tried to reach larger audiences. I want to talk about the photobook and photoland bubbles a little later. But do you think that you had a chance to at least expand that bubble a little bit or even break out of it?

RH

We were mainly exhibiting in photo institutions, at photo festivals, not so much in contemporary art museums. From there, we also reached beyond the bubble with the help of traditional media: magazines, newspapers writing about our work, and then people being interested in looking it up. To give you an example, around the day we got banned from Russia, we had 100,000 unique visitors from Russia on our storytelling website. Alternative online news channels in Russia were reporting about it. So everybody was checking our website. That was definitely beyond art and photography circles.

Another example, Aperture published 4,500 books, and they were all sold before the Olympic Winter Games. Four thousand five hundred is quite a substantial amount of books. Now we have second edition that is running towards the end. We’re not talking about only 250 or 750 books or whatever the numbers might be these days. What helped tremendously was that the region where we worked was closed for journalists six months before the Olympics. So it was no surprise that many editors from major newspapers checked out the book and knocked on our door. When Le Monde or The Guardian publishes an article about it, then you reach far. All these big news channels in different countries were reporting about our project. And very often not in the art section, but in the foreign-affairs pages. There, you reach significantly larger numbers of readers. We always stipulated that there were references to our book or website. That helped tremendously with the visibility of our work.

JC

And then you took a little time out. Or maybe I shouldn’t call it time out, because your old employer might get upset. But you went into teaching.

RH

Especially during the last two trips to Sochi, I didn’t have any energy to once again approach people and have conversations. I was exhausted. So I felt that I needed to take a period off from being an active photographer. When the job offer arrived at my door step — co-head of the BA and MA Photography at the KABK Royal Academy of Art — I just decided to go for it. And it turned out to be a great experience.

Of course, this decision was also related to the fact that I just had had my first child, and the second child was coming up. I wanted to be more at home in those early years of my children’s lives. Having a steady income would be nice too for a while. The job gave me the ability to have a mortgage on a house, which is near to impossible for freelancers in the Netherlands. The moment I had a permanent contract after two years, I immediately bought a house. So there were advantages for a while. However, when I announced this temporary career switch, everybody warned me. From Martin Parr all the way to my mother saying “this is the end of your maker’s career.” I always replied: “No, I can combine it all.” But no. Unfortunately, it turned out to be impossible for me. Officially, I had a three-day job. But it was always double the amount of time and it made it impossible for me to sustain my maker’s career.

Anyway, I felt very privileged, I had a nice job at an ambitious academy with great students. I had permanent contract, a steady income, a mortgage and didn’t have to travel too much. I had a great life that I could continue easily like this for years. But after a couple of years, I told my colleague co-head: “It’s too bad, because being co-head absolutely is the second best job in the world. But for whatever reason I still want to be a photographer.” As a result I took an unpaid six-month leave of absence. Within a month after my return I told her: “This is not going to be half a year, this is going to be forever.” And I quit. That’s now one year ago.

It was a big step for me to find the courage to say: “Hell yeah, I’m burning down everything and I am going back to my insecure maker’s career.” But so far I’m very glad I did. Despite all the uncertainties, I think it’s just incredible to be a photographer and work on self-initiated long-term projects.

JC

You decided to work with Arnold van Bruggen again. And you started the project The Europeans. I think the structure is very similar to The Sochi Project. But I think there are some differences. I don’t know if this is true, but I think you don’t work with galleries any longer. Can you talk about that?

RH

I didn’t feel very comfortable working with galleries in general. You know and I know and every reader of your website knows that art fairs are hardly about content. They are about aesthetics and money. My work is humanistic and often about violations of human rights or poor living conditions. Seeing my work as a sales item at an art fair makes me feel uncomfortable. There also is the fact that the most marketable two or three works are usually displayed. I work in series — that’s why I like books so much, and if you only pull a few works out, the content gets blurred.

My students often asked me: “If you feel uncomfortable, then why are you a part of it?” The answer was very simple. Like every artist, I was hoping to make enough money to sustain independent projects. I did make money, but not so much that I felt that it was going to be the part that’s really sustaining my work. Five years ago, I decided to stay closer to myself and stop working with galleries. I know more photographers struggle with this, but few speak up about it.

Was that a smart decision? Most important, it feels good to no longer be part of this deeply conservative, capitalist art bubble. I’m not against selling work, as I also need to fund my projects, but the setting of an art fair just doesn’t feel good to me. Financially, by the way, it hasn’t turned out badly. I sell more work now than I did during my gallery times, directly to museums as well as to private buyers. Without profit sharing.

JC

I read that, that the people in your pictures get a fraction of the money that you make from a print sale. Is that true?

RH

Yes. What do we think about it? It’s true, but I’m still in doubt. I’ll explain after tell me what you think.

JC

When I read this, I thought it’s actually brilliant. It solves some of the problems that I’ve had for a long time. I have a problem with the fact that a photographer goes out into the world, and often the people that are being photographed are poor people or disadvantaged people. The pictures are then sold to rich people, and the photographer makes a career out of that. That’s fine. But the people in the pictures don’t really get anything. Their pictures maybe hang in a museum, or their faces are well known. But nobody even knows their names. I’ve always wondered why they do not get anything other than an invitation to the exhibition or maybe a small print? So when I heard about your model I thought it was great. In some ways, you share responsibility for what you make. But I don’t know to what extent these thoughts were in your head when you came up with this.

RH

Once I make a portrait of anyone and publish it in a book or in a magazine, I don’t feel uncomfortable. I see it as my calling to document the world. Including people. So making portraits is part of my profession. I honestly explain my work the best I can to everyone. People are free to participate or not, they sign a consent form afterwards. If a portrait is published, in a book, magazine or newspaper, I hardly ever make any money from it.

Once one of those portraits is being sold for a lot of money as an artwork in an edition, I become a bit uncomfortable. On the one hand, such transactions are necessary to generate enough income to continue my projects. On the other hand, I feel that is the time when the person portrayed may also benefit from the sale of work.

I never tell people in advance that they could possibly make some money from the photo. I’m afraid I’ll end up in a grey area, where people agree to cooperate because they hope to make money from it. Or that it affects their behaviour in front of the camera. In my practice, the chances of a portrait being sold as an editioned print are incredibly small, maybe one in every hundred portraits.

JC

Out of the blue, they get a check from you in the mail?

RH

The way this works is that 1/3 of the money goes to the person, 1/3 goes to me, and 1/3 to our project The Europeans. So yes, I contact them. It’s not a lot of money, usually just a couple of hundred euros. But people are surprised. I don’t have a lot of experience yet. The selling of editioned works from The Europeans has only just begun. I am now in the process of finalising the first transactions.

Honestly, I am a bit afraid of possible outcomes. What if this becomes more regular and more photographers are using this system? As a result, people might ask any photographer whether they get money from it. Whereas I believe that making someone’s portrait is not something that you should have to pay for. And of course, in my new system, that’s not what I’m doing. I’m only paying to someone if I sell the picture, based on the idea that sharing is an incredibly beautiful thing.

For every chapter within The Europeans, I’m portraying 300, maybe 400 people. Out of all these portraits, three, maybe four photos are sold as an editioned print. The other people don’t get anything. I don’t want to create a shady field where people are going to ask for money from photographers before they are portrayed. That’s my fear with this system. I don’t want to make it more difficult for photographers than it already is these days. Hence my doubts.

Another point of attention: What if the person in the image is — in my opinion — a really nasty person, let’s say, a Nazi guy? I don’t want to support those activities. That doesn’t feel good. Another thing, in case you portray children, you have to pay the parents. I hope that they put the money aside for later, but you never know. So I started something, and I thought I’d do good. But now I have my doubts about all these kinds of things. Actually, I really have no clue what I’m doing. But that’s always when you start something new, right?

JC

I was just going to say that you did similar things with The Sochi Project already. You tried a lot of things just to see what happens.

RH

Some things completely fail and other ones are successful. Fortunately for me, people generally only look at the success stories. I am seen as the photographer who has introduced new funding models for long-term photography projects and constantly questions the ‘conservative’ art and photography scene by using new forms of presentation, reaching beyond the intellectual elite. I am quite proud of that. But of course, many things I tried failed. That is less in the spotlight.

JC

Here’s one other thing I wanted to talk about: the isolated world of the photobook and photographers staying in that bubble. I had the feeling that you have a lot of opinions about that. How do you see this whole thing?

RH

The short answer is I share your opinion. Actually, I am always a little bit in doubt about how to talk about this. I am passionate about photobooks. I love photobooks, including photobooks that are being made without a real reason to make them. I think those books are sometimes brilliant. So it’s very difficult to be harsh towards this world where things are made with commitment, care, and passion.

But the fact is that not enough photographers think before they publish a book. Delphine Bedel, founder of META/BOOKS once asked: “Is your book worth killing a tree?” That’s a very important question. I think photographers nowadays have the obligation to think about the impact of a book. There are so many photographers producing wonderful and smart photography projects. But once they start thinking about presentation of those projects, it seems that 99% lose their capacity to creatively think. All they think of then is ‘book and exhibition’ without wondering what purpose that serves.

I really admire photographers who have the rare capacity to match the presentation of their work to the core ambition they had in mind. People like Rafał Milach, for example, making newspapers to hand out for free among protesters. To support them, to give them a voice, to make them visible to future history because the media ignores them, even to facilitate posters. Or Zoe Strauss, who presented her work under the I-95 highway to bring together different groups in Philadelphia. You really cannot find these different groups in a museum, no matter how hard they try to bring them in. Or Mark Neville who is sending out 750 complimentary copies of his new book Stop Tanks With Books to ambassadors, members of parliament and other policy makers. The aim is to put pressure on ending the war and withdrawal of Russian forces from occupied territories. These kinds of projects are far ahead of all those narcissistic photographers who would like to see their work reproduced in an expensive and beautifully printed book with their name on the cover. The annoying thing for photographers who explore new forms of presentation and appeal to different audiences is that the art world — which calls itself progressive, but in real is the opposite — often ignores such projects, while rewarding those expensive narcissistic book projects.

JC

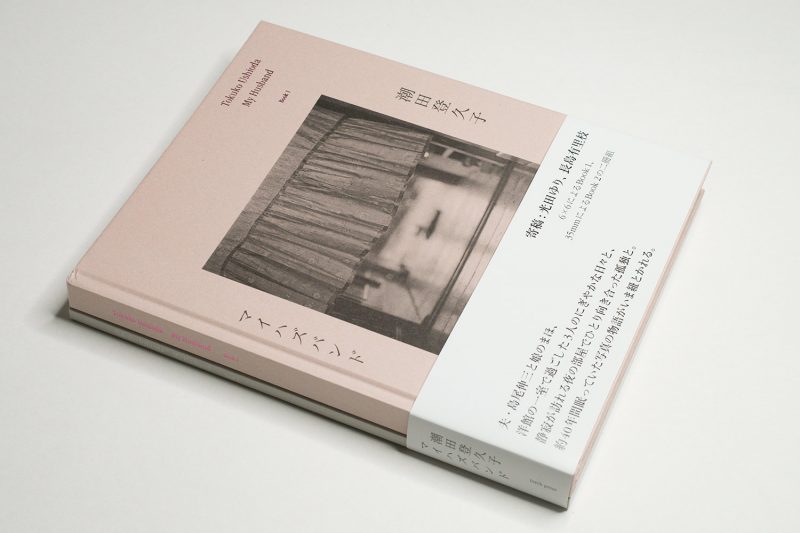

With your latest book, you explicitly tried not to make a posh, big book.

RH

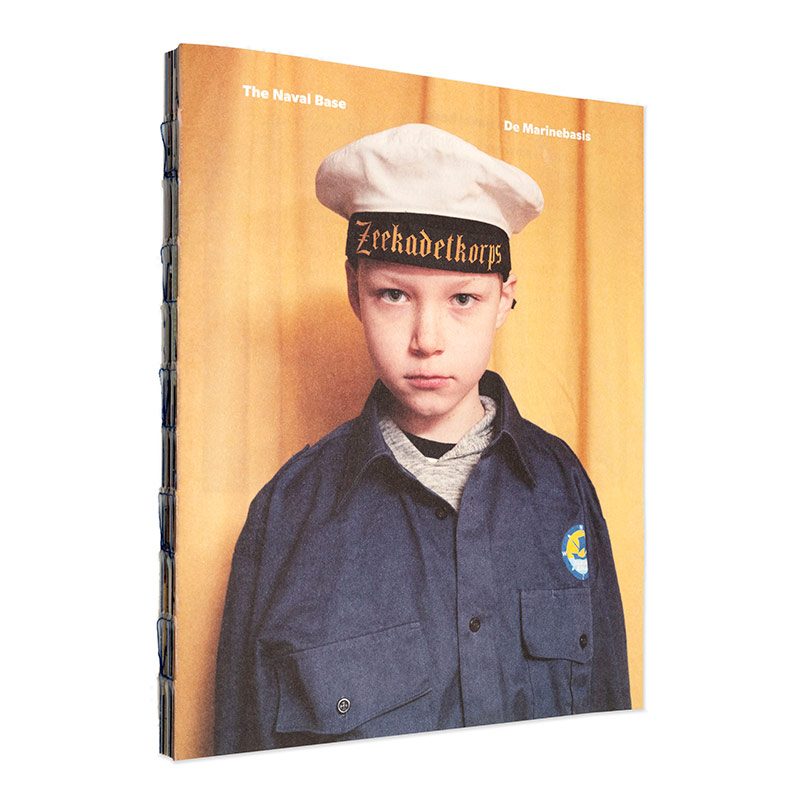

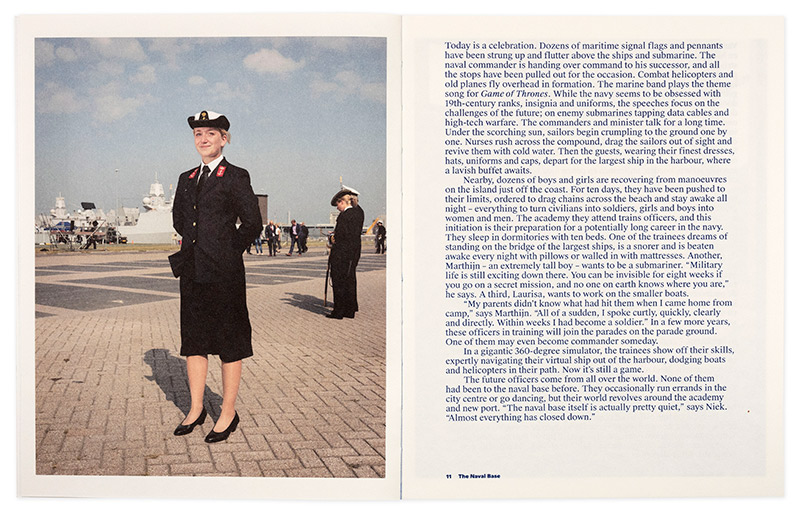

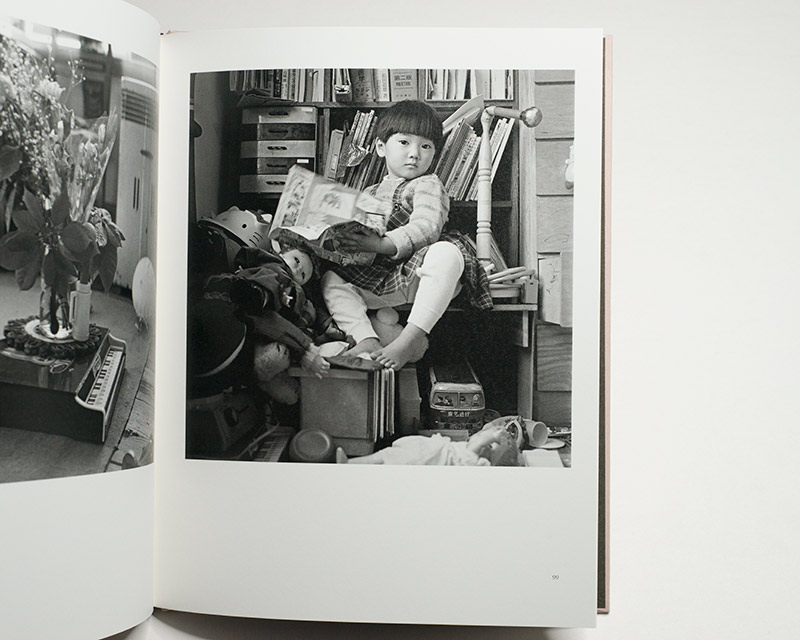

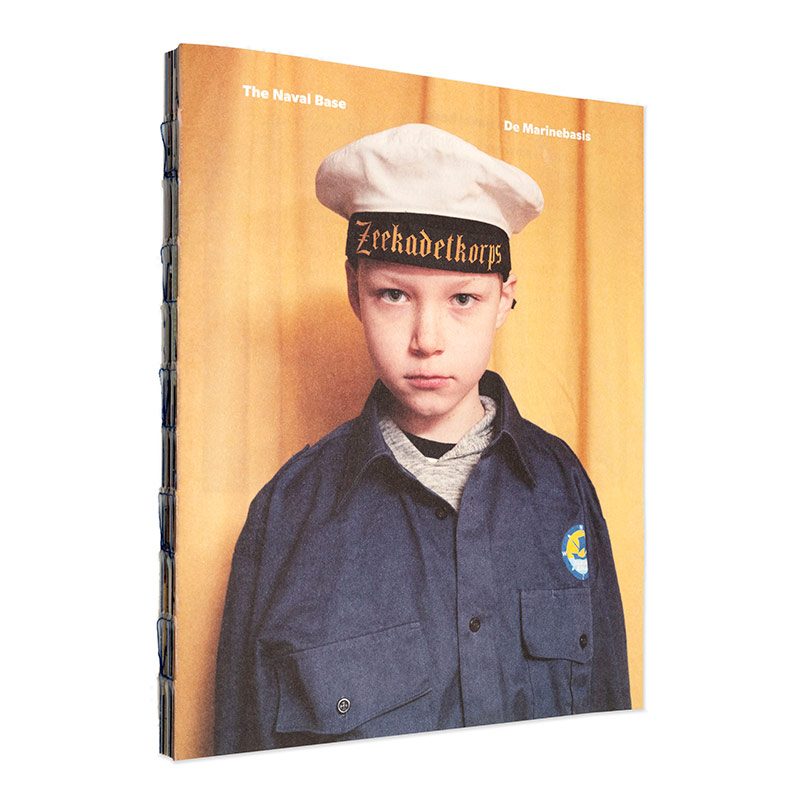

It is not really a book, we see it as an interim publication, an ephemeral and raw presentation to continue the local dialogue and elicit responses that are valuable for the continuation of the project.

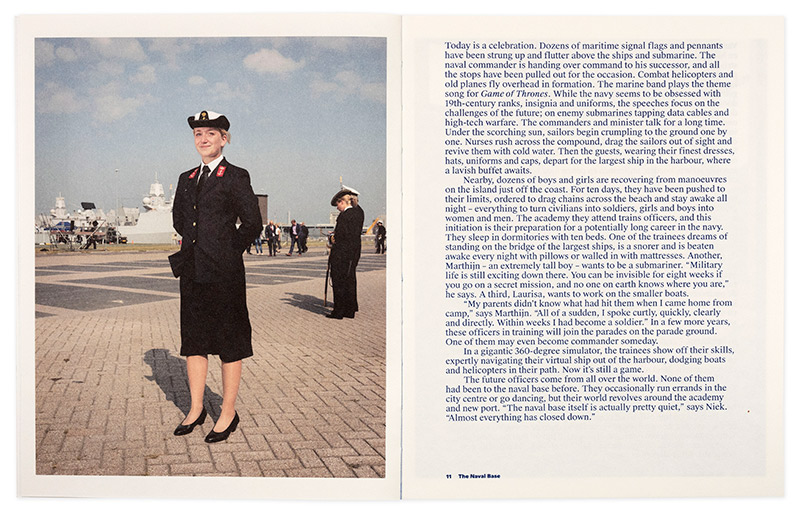

For The Europeans, we produce work in different heartland regions. That’s where we also first want to present the work. It doesn’t have to be a presentation at an art institution. It can be a shopping mall as well. We try to connect to a broad local audience. And we have devised a strategy on how to achieve this. First of all, we work together with a local newspaper. And we create stories, portraits of local people for this newspaper. That’s working really well. We reach loads of people by publishing in a local newspaper. This is how we manage to connect local people, but increasingly also pan-European. The larger goal of our project is to counteract rising populism. We think that we will increasingly achieve this in heartland regions. Once we are finished in a region, we invite people to join us for a drink at the exhibition opening. So we collect reactions and feedback. There we also have our self-published publication, which is all about them and the region where they live and work. In those heartland regions, hardly anyone will buy a photobook that costs €39.50. So we decided that the accompanying publications cost €9.50. That’s why it’s not big and posh.

JC

It’s not an overwhelming large book. It’s this sort of like unassuming pamphlet, which doesn’t telegraph “I’m so precious.” I think aside from the price, that’s really important.

RH

Of course, these are not hardcover expensive books. Taking financial limitations into account and thanks to our great designers Kummer & Herrman, we think we really produced a nice publication. The selling price is a little below cost price. We solve that problem by wrapping part of the print run with a hard cover, including a print, and selling it for 120 euros. So the buyers of the hardcover edition are helping us target a broad audience with our project. And it works. That’s the nice part of it. When we have an exhibition opening, loads of locals are buying the publication. They bring it home and they really read it. And we receive feedback. It works perfectly.

So reaching a local audience works. Yet at the same time, we also try to anchor the work in the world of art and photography. Because, let’s face it, that is necessary to be able to benefit from funds and to sell work to private and institutional collections. We’re also looking towards The Europeans‘ final work, around 2030, with major exhibitions and a grand reference book that aims to still be on the shelves of libraries a hundred years from now. It is very challenging to reach both audiences — a local audience in heartland regions and a global art and photography audience.

The first problem we encountered with our super-cheap publication was that specialist booksellers were reluctant to sell the book. Simply because there is no money to be made. One famous online bookseller told me that he does not sell books under 25 euros. And frankly, I do understand. The conclusion is that if you make a financially accessible book, it will not be available in bookshops. And as a result, it becomes less accessible. We had not realized this beforehand.

We are now considering how to solve this dilemma. One option is to double the price to €19, but provide a 50% discount during local presentations, so the work still costs €9.50. Perhaps one of the readers of your blog has an idea?

JC

All of that goes back to the original problem, doesn’t it? Of the art community being so removed from the rest of society.

RH

In his essay The Barbarians: An Essay on the Mutation of Culture, Alessandro Baricco wrote about what could be described as a global shift in consciousness regarding high and low culture. The way we still largely experience art today is a relic of the Romantic era, when museums and theatres were built with entrance fees that were only meant for the elite. Within these walls — accessible only to the wealthy — art was displayed. Today, we still behave according to those unwritten rules. It is not for nothing that the vast majority of young artists want an exhibition in a renowned museum. When you have achieved that, you can honestly say that you are a real artist.

In 2006 , Baricco questioned this old-fashioned way of thinking. He argued — and I fully agree — that art will increasingly go beyond the walls of museums. Fortunately, this is already happening on an increasing scale. It was interesting to see the Turner Prize awarded to an architecture collective called Assemble in 2015. They won the UK’s most important art award for their work on the Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool. The project is a collaboration with the residents of a rundown council-housing estate to clean up the neighbourhood, paint empty houses, and establish a local market.

Reviewers and critics were in shock and stated that’s not real art. To those I would like to say: Wake up people! Things are going to change. The art world is in a major shift from the romantic era towards a new era. That’s fantastic. Why is an insanely expensive framed photograph by, say, Andreas Gursky considered more important in the art world than a free newspaper by Rafal Milach?

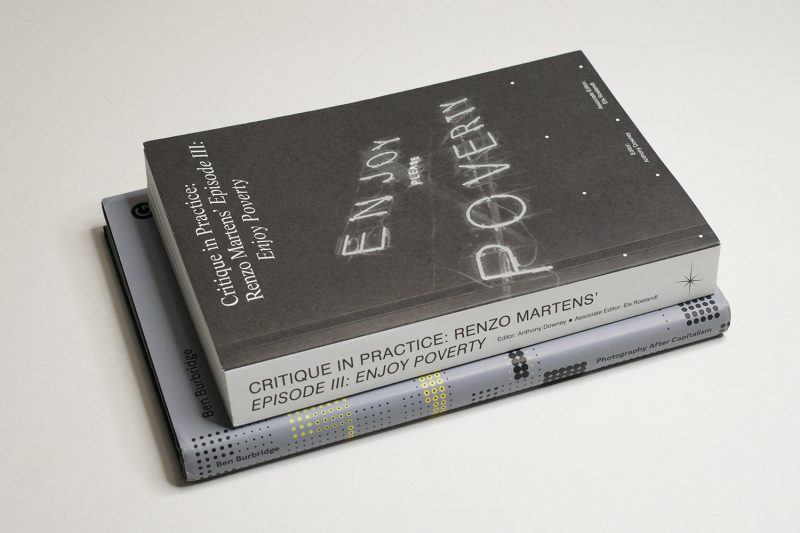

Buy this book. The entire amount (47.50 per book) will be donated to Red Cross Ukraine.

This is the 2nd edition of our book An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (Aperture, 2015). On the cover we used the quote ‘This is the new face of Russia, our Russia’, from a propaganda speech made by the CEO of Sochi 2014, a Putin-supporting clown, during the closing ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Sochi. The book — released in first printing before the Winter Games — extensively covers the blatant human rights violations under Putin and his regime. We regularly received a frowning look, wondering if we hadn’t exaggerated things. After all, it couldn’t be that bad in Russia, could it? Again and again we explained: The Putin regime violates human rights on a large scale, is corrupt, criminal and dehumanizing. Disguised as a democracy. Read about it in this book and support the Ukrainian Red Cross at the same time!