It might be a sign of a great photobook when many aspects of a viewer’s biography come together to superimpose themselves on the pictures in such a way that the work itself almost becomes secondary. Of course, it never becomes secondary — how could it? But if all art reflects some of the viewer back to her or him, great art does it particularly well. What is reflected back is a combination of the viewer’s biography, the circumstances around her or his socialization, the culture and society s/he grows up in, and an assortment of random other things or events, which under any under circumstances would never come up.

Tokuko Ushioda‘s My Husband immediately made me aware of this process the moment I picked it up to look at it. I had met the photographer and the husband in question, Shinzō Shimao, during one of my trips to Tokyo. Truth be told, even though they had both spoken about their work, it had been Shimao’s image that had stuck with me. After a presentation of his work, he had given a very underwhelming lecture about photography itself. While working on this essay, I found him being described as “a charismatic yet cynical artist”. This felt familiar.

None of that should obviously matter, given that in the end, all I have now is the book. Still, when I see Shimao glare at me in some of the pictures (well, not me, his wife’s camera and maybe, by extension, his wife herself), I see a younger incarnation of the same man who almost four decades later would deliver his thoughts around photography. I’ve tried many times to forget the impressions from that encounter. But the more you try to un-remember something, the more the opposite happens.

Interestingly, while the book (or rather books: there are two — more on this a little later) are entitled My Husband, I’m thinking that this might mislead a viewer. After all, the photographs speak a lot more of Ushioda’s own life at the time when they were made than of only the husband. In fact, Shimao is included in only a relatively small number of them.

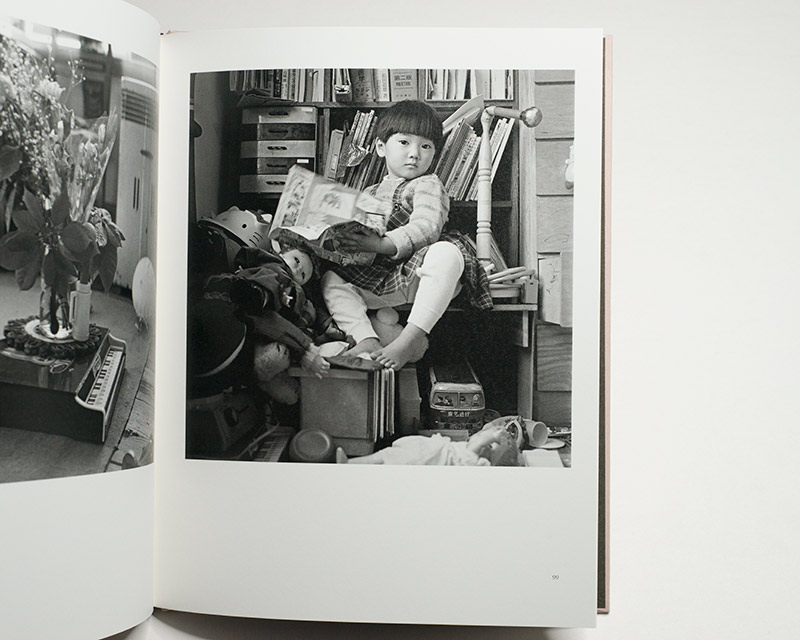

There also is their impossibly cute daughter Maho with her big, big eyes. She is referred to as Maho-chan, where “chan” is a Japanese honorific used for people one is close to that has no equivalent in English. Maho-chan also happens to be the title of a book Shimao published in 2004. Lastly, there is the house they lived in, an old Western-style house, the living room of which featured very large windows (ideal photo light).

More often than not, family photography depicts the vibrancy of life in a group of close relatives. Where it does not — think Larry Sultan’s Pictures From Home, it’s usually a combination of the tool (the camera) and the underlying conflicts that freezes things into stasis (unfortunately, this sentence would make more sense for a reader who is familiar with the book I’m currently shopping around; I’m hoping that at some future stage, my thoughts on Sultan’s work — as well as Fukase’s, Billingham’s, and Epstein’s — will be accessible for a wider audience).

Here, there is a curious absence of vibrancy. Maho-chan happens to be at an age where children are very active, but somehow she is not — at least not in the pictures. It’s the mother taking the photographs, which offers an immediate explanation: from what I’ve been told, as a photographer and mother, your choice always is to be one of them at any given time, not both. Ushioda’s choice is clear from her work.

This brings me back to the thoughts I started out with. At the end of the (first) book, there are two essays. The first was written by Yuri Mitsuda, an art critic. The author of the second essay is photographer and writer Yurie Nagashima who might be familiar to regular readers of this site. In my interview with her, Nagashima spoke in detail of the struggle of being a photographer and a mother, in particular in a country such as Japan where men traditionally don’t do any housework (it’s obviously not much better in most other countries).

There are too many details to repeat them here. Nagashima’s essay is a masterclass in learning how the background against which both Ushioda and herself had to live as mothers and photographers informs numerous details of the work. For example, the quietude of the pictures simply arises from the aforementioned fact that doing two jobs at the same time is impossible. It was the ends of the days when there was time for photography. If you look carefully, you can actually see this. There are those huge windows that allow in a lot of light. Yet in many of the pictures, available light comes from lamps or candles.

Even the camera choice might have something to say. Nagashima wonders “if her choices about the techniques and cameras she used were informed by her being a woman.” Recounting her own experiences in the 1990s, she writes that “Ushioda-san would perhaps deny this was the case, but as a woman traversing an androcentric world, photographs with a 35mm SLR would seem more likely to be dismissed for no good reason.” (p. 129; “san” is possibly the only Japanese honorific familiar to Westerners, roughly the equivalent of “Mr.” or “Ms.”)

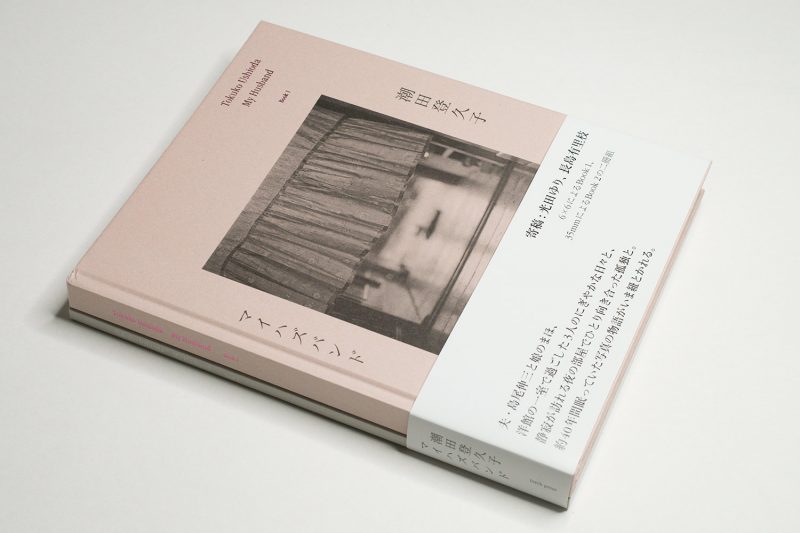

As I already briefly mentioned, there are two books. They are divided into camera formats. The first, more expansive book (a hardcover) showcases square-format photographs taken with a Bronica S2 (source). The second book (a softcover) contains photographs taken with a 35mm SLR. As a set, the books are combined with a belly band (“obi”) that wraps around the first books’ front and second book’s back cover (obis typically advertize the books; they often include a quote by a well-known photographer).

There is considerable overlap between the two books (how could there not be?). In the second book, there are many quiet observations made when there was time, when there was rest. But this camera, the 35mm one, also left the house, and it was used in more fluid, social situations. To me, the stepping out of the zone of quiet contemplation feels somewhat welcome, even as ultimately the strength of the work lies exactly where it remains quiet.

I imagine that this aspect might have posed more than one conundrum for the editors of the book who were given access to prints and negatives that had been stored away for decades: their task was to locate the spirit of the work without having it stray too far from the person they know , Tokuko Ushioda. After all, how do you go about bringing out the artistic strength in a body of work while acknowledging the maker’s vulnerability — without having the scale tip too far into either direction?

As someone who has edited two books of photographs recently that could be situated in exactly this spot, I can only applaud the editors for having done an amazing job. The photographs sit right at that sweet spot that, and this is something we as viewers should try to keep in mind, might not quite be as sweet for the artist herself. We don’t know, and we might as well also acknowledge that we don’t have to know.

My Husband is a revelation in more ways than one. To begin with, it gives exposure to a Japanese photographer who is barely known (if that) in the West (photobook collectors and those who looked at the recent What They Saw carefully might remember the earlier Ice Box book). This is a most welcome fact, given that the Western discourse around Japanese photography is still so centered on the mostly male (and very macho) usual suspects (Rinko Kawauchi being the one notable exception). Every step towards allowing Western audiences wider access to the very rich world of photography from Japan is so important.

Furthermore, as I indicated above, these are family photographs (a rich genre) by a woman artist. But in many ways, while ostensibly centered on the home, the young child, and the husband, the photographs really focus on their maker. To some extent, this observation is a lazy truism — all photographs say at least something about their maker; and yet some photographers allow more of their own lives enter into their work than others. More often than not, a photograph speaks of Ushioda’s desire for quiet respite, especially in the first book.

For sure, I wouldn’t want to overinterpret what I take away from My Husband — I have no children, and I’m also not a woman. But I can’t help but feel that what Yasujirō Ozu centered on in many of his movies can also be found here: the impossibly quiet and fraught drama of family life.

There is something uniquely Japanese about Ozu’s movies, given the height the camera is placed at — it’s right there in that social space near the floor where people’s eyes meet when they sit together. In her own ways, Ushioda achieves a very similar effect with her photographs. Time slows down, and the small idiosyncrasies of family life as seen by a mother/photographer are brought to the fore.

Highly recommended.

My Husband; photographs by Tokuko Ushiuoda; essays by Yuri Mitsuda, Yurie Nagashima; two volumes, book 1: 122 pages, book 2: 76 pages; torch press; 2022